A Conversation with Rosalind Fox Solomon

"I was just a strange, different woman, who walked into people’s lives."

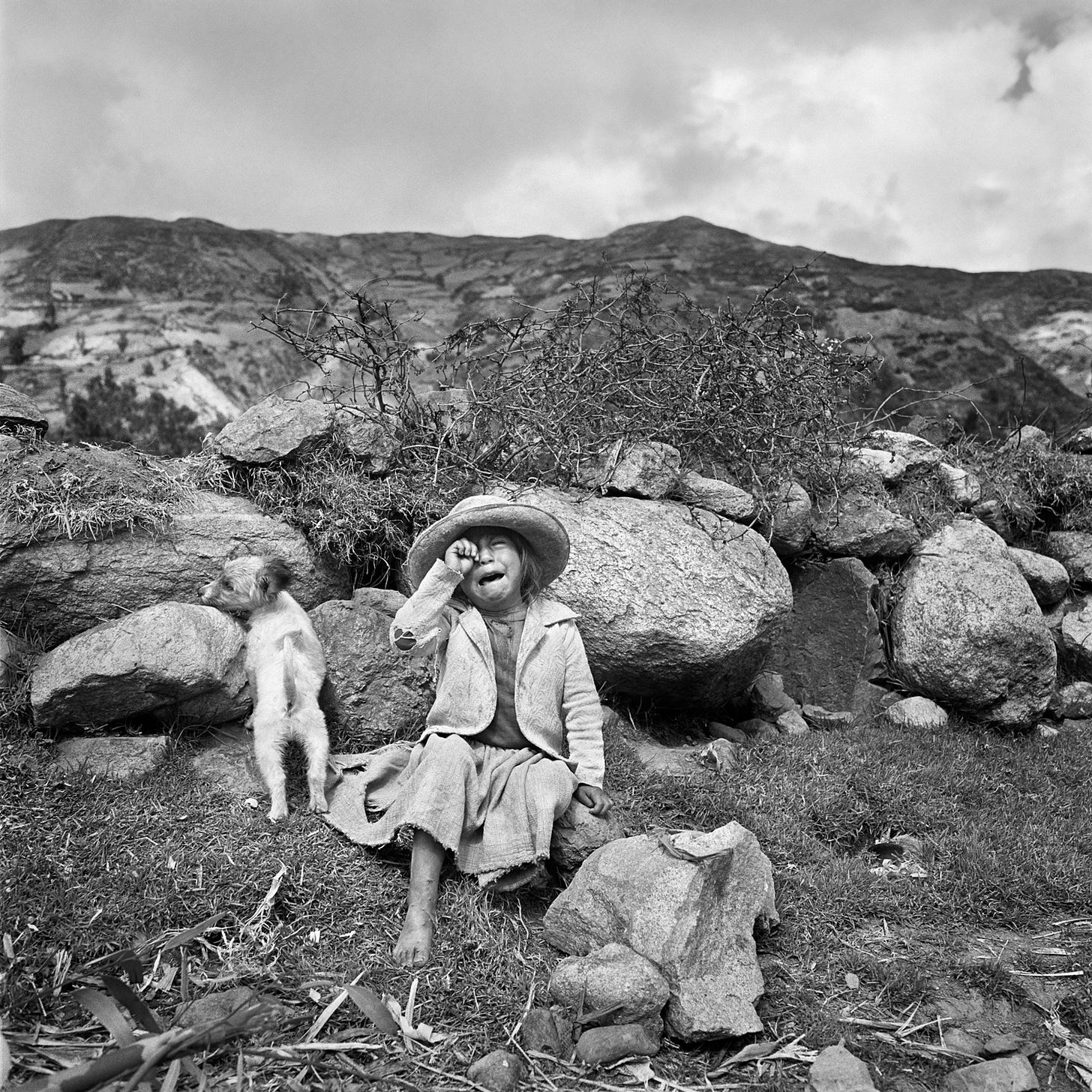

Rosalind Fox Solomon is one of the giants of photography whose work never fails to make itself felt. Her subjects have included ritual practices in Peru, Guatemala, Brazil, India; the racial dynamics of a post-civil rights American South; and the social landscape of AIDS in the late 1980s. For more than five decades she has travelled the world to make photographs, creating a vision of people and landscape, mystery and strangeness, “chaos and pressure”1.

At Paris Photo in November, the sense was of a moment of fruition for Fox Solomon. There were extensive presentations of her work by two galleries: her earliest project, documenting Scottsboro Alabama First Mondays Market (1972-6), was shown by MUUS; and Julian Sander (who represents Fox Solomon in Europe) showed later work, with a grid of framed prints on the outer wall, and a three-panel high selection from Portraits in the Time of AIDS pinned directly to the wall as you made your way into the hidden centre of the booth, creating an effect both fragile and overwhelming.

During one of her talks at the fair with Aperture’s Sarah Meister, Fox Solomon recalled her days of tuition with Lisette Model, and Model’s instruction to “go for the strongest thing; go for the difficulty.” Looking at Fox Solomon’s photographs today, in a time of increasingly collapsed distance between art and commerce — especially if one’s main interface with photography is on the frictionless brightness of Instagram — can feel difficult indeed, even something like a shock. The images are full of friction and strain.

This, after all, is Rosalind Fox Solomon’s enduring power: a refusal to smooth the edges of a disturbing world. The flash and the contrast, the angles, the details that pull in from the sides — the work is stark. It’s all edge, and looking at these photographs pushes you into it. She wants to trouble you, and with good reason. “Our times are not bright,” she wrote to me via email, explaining the selection of photos she’d made for this newsletter. “If the photographs unsettle us now,” Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa has written about her work, “it would be well for us to question the virtues of comfort in times like these.”2

Now 92, Fox Solomon is seemingly indefatigable: she’s working on a new book, her work is held in collections all over the world, and continues to be acquired by major institutions. I was extremely honoured, then, that between her various talks and appointments at Paris Photo, she found the time to have this conversation with me.

Alice Zoo: I wanted to start by asking you about ritual. You spoke a little bit about this in your talk yesterday — why are you drawn to photographing ritual?

Rosalind Fox Solomon: Early on in my work, I was working through problems in my own life, and I was interested in how others cope with situations in their lives that seem difficult, or impossible to resolve. That was my basic interest in it. And I’m interested in the visual aspects of ritual too — but it was the emotional part of it that attracted me.

AZ: Do you feel like ritual has a real effect in the world, or is it more about the action?

RFS: Well, I think it’s whatever people put into it, it’s what they read into it.

AZ: Do you have rituals of your own?

RFS: My rituals are personal, as opposed to the group rituals that I photographed. I work regularly, and keep up with the news through reading and watching television.

AZ: I was also interested, yesterday, in what you were saying about people comparing your work to Arbus, and how it had disturbed you. Could you tell me a little more about that?

RFS: Well, at the time that I was hearing that, the work that was out was what they talked about as Arbus’s freaks. And I didn’t think that my pictures were related to that. And I didn’t want to be considered… I wanted to be considered as myself, that’s all.

AZ: There’s a tenderness that comes through in your pictures, as well as a strangeness; so I can see that the idea of “freaks” doesn’t sit easily with your work.

RFS: I do use a square format and I use flash; there, the similarity ends. Arbus committed suicide a year before I began my studies with Lisette Model. Lisette told me that I was not like Arbus. When I took a portfolio to MoMA, John Szarkowski told me that I shouldn’t show my work too soon. He said, “People will think that you’re like Arbus, and you’re not.”

I did admire her work. And I liked using a flash. I found the flash to be very helpful in my work. I couldn’t have done so much of what I did without it.

AZ: Why?

RFS: Because I could work very quickly with flash, no matter where. I learned how to work very quickly. And if I was photographing a parade, I could do it: I could generally figure out the background lighting, and I could then just click my shutter. It was very easy to get a good basic negative using a flash, and without it I would’ve had to stop and figure out the natural light, and it would’ve given me a different way of photographing.

AZ: Do you find, while you’re photographing, that it’s a practice that relies on being fast and agile, or are you slower and more considered?

RFS: It just depends on the situation. If it were a public situation with moving people, I naturally have to work quickly. If I’m doing a portrait of somebody, I usually take time. It doesn’t have to be a tremendous amount of time. 15 or 20 minutes.

AZ: You came to photography relatively late in life. Before you were photographing, what was your creative life? Did you have any other kind of creative output?

RFS: I would say no. I’ve always liked writing, but I didn’t consider it an occupation.

I think it always interested me, and who knows how I was. But that was the only creative outlet that I had — I can’t think of anything else. So photography really led me in a different direction, and it allowed me to deal with not only the outer, whatever I was seeing, but also with my inner self, which is very important to me.

AZ: I feel the same, because I’m photographing and writing, and I feel this tension between the outer and the inner, and I’m trying to bring them closer all the time; so I’m really interested to hear you say that. What kind of thing did you write, what kind of thing are you writing?

RFS: Now I’m pulling together some things, I’m working on a book. I’m planning to use some of my writing in small, short paragraphs that might be woven in between it. I don’t know, it’s very early on in this book. And then some personal things that I have written, and will write. And it won’t be linear.

AZ: So this is collecting together notes that you’ve been taking for how long?

RFS: I have journals from a number of places, so I’m taking a look at those. That would be the older things that I might draw from. And otherwise, sometimes just free-thinking, writing whatever comes out of my head — stream of consciousness.

AZ: And are you reading a lot?

RFS: I don’t read enough. I really love reading, but I do the best I can to read the newspaper and magazines; I seldom am able to read a whole book. Because I still work — and that comes first for me.

AZ: I was reading in your book about this idea of obsession, and obsessing over things, and I was wondering: what are you obsessing about now?

RFS: I suppose what I’m obsessing about is old age.

AZ: Your own? Other people’s?

RFS: My own.

AZ: And so aside from work, what about play?

RFS: Play is spending time with friends, seeing movies, art, opera, theatre with them, or just having a good dinner together. And I love to go to dance, I go to theatre and dance. I did get season tickets for the dance theatre this year. And I haven’t seen as much of theatre as I would like, recently, but the public theatre is around the corner from me. It’s very easy to go there.

AZ: I can see all the dance and the theatre coming through in your work.

RFS: I don’t go to as many [art] shows as I would like to, either, because I always have work in my studio. But there was a writer, many many years ago, who told me: look at paintings. And that will be helpful to you, in making your photographs.

AZ: Yesterday you were talking about feeling like a strong woman during your travels, and feeling a sense of independence, and that being an important motivating feeling and factor in your work. Could you say more about that?

RFS: Well I was married, and there was the relationship between me and my husband… You know, relationships were different then, expectations were different. And I always had outside interests, but I felt — sometimes I was treated like the little woman. My mother was definitely in that mould. So going to these places, and being independent, and making friends for no good reason: just walking into people’s lives — like the nuns, that was really an incredible experience — it just made me feel very strong, that I could go anywhere, and I would always make friends with people, and they always helped me. And that was just so outside of my normal, everyday life, doing that. And it was so rewarding. And when I thought of how I looked, when I was in the Andes — you know, I didn’t think of wearing make-up, or of looking any particular way.

AZ: The freedom of the unburdening of the self, not having to be oneself anymore. The outward impulse, instead.

RFS: Yes, absolutely. To be accepted in different cultures. To be allowed to do photographs.

AZ: Did you find photography helped you be accepted in that way? You know, what people say about it being a passport to anywhere?

RFS: I think so, but also I was very lucky at that time. I was just a strange, different woman, who walked into people’s lives.

AZ: What do you feel like photography has given you in your life? If it hadn’t been there, what would be missing?

RFS: I think photography gave me the ability to be independent. To have a real, a strong path in life, that was completely outside of my domestic life. And it was something that motivated me strongly. It was the idea of seeing and knowing different kinds of people, and different cultures, which was always important to me, from the time I was 23 and went on the Experiment in International Living. And so I wasn’t just interested in just taking pictures, I was interested in knowing about people’s cultures. I was interested in knowing about them. And sometimes I photographed people who I would be… Afraid isn’t the word, but I photographed people who I assumed were quite prejudiced. That was in my head, thinking about what they were thinking of me, and how they felt about it.

That I just managed to do these things, in so many different circumstances, whether they were prejudiced or not — how did I do it? I don’t know, I just made up my mind that this was my job, this was my job in life: to be a photographer. Something I learned how to do, and that I knew I could do, something outside of myself, something outside of my marriage, something outside of my own culture. It was such a wonderful kind of pursuit for me, and for so many years. Well it still is, and also feeling in my old age — you know, I have things to do!

AZ: It’s very inspiring, that there’s so much to look forward to, all through the different phases and decades of life — like with these recent acquisitions,3 for example. How amazingly exciting, to have these things happen in your nineties.

RFS: It’s wonderful. I’m just really glad that I’m here to experience it. And it’s a lot, because look — a lot of it could’ve happened 20 years ago. The pictures were taken a long time ago. So it’s really great for me. It’s very exciting for me, to have my work recognised in the way that it’s being recognised now. And that’s the truth. It’s very exciting.

It’s comforting to know that MUUS has acquired thousands of my photographs. And to have Julian Sander representing me; I feel so fortunate. I knew his father, Gerd, and his mother, Christine. They showed my work at their gallery in Washington DC in 1977. I knew the family, and I visited their home, all that. So it’s quite a remarkable thing for me, that that’s happened. I can’t say enough. I mean I’m really fortunate, in my nineties, to have my life opening.

AZ: It keeps opening!

RFS: Yes, it’s like a flower that keeps opening. Right now, that’s what it feels like. And I think, you know, there’s just going to be many more things that will happen now. And of course, I’m in a place where it’s not hard to accept it. You know — I feel, ok, yes: we’re right to do things with my work, I like my work, and my work deserves it. And: good! Here it is.

AZ: Here it is. Well congratulations, and thank you so much.

RFS: Thank you.

Every month I’ll be asking each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue.

Rosalind Fox Solomon’s recommended reading:

Five Families — Oscar Lewin

The Beauty of the Husband — Anne Carson

A huge thanks to Rosalind Fox Solomon, and to you for reading! You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below.

‘The Photographer Who Captured How Whiteness Works in the American South’, Doreen St. Félix, The New Yorker, 2018

‘Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa on the play of freedoms in Rosalind Fox Solomon's Liberty Theater’, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, Mack Books, 2018

The Rosalind Fox Solomon Collection was acquired by MUUS in 2021, and Portraits in the Time of AIDS was acquired by Washington DC’s National Gallery of Art in October of this year.

Great interview, thanks Alice.

I’d never heard of Rosalind Solomon. What a great article and I just love the tension in her work. Thank you