The first time I remember seeing the work was as a carousel of fruits and vegetables being chopped at food markets around the world. A hand holding a stack of cactus leaves waited while the other sliced quickly at the stack, a bunch of palitos tumbling into a bowl. A man was using a thick, aggressively sharp-looking knife to carve a precise spiralling shape into the flesh of a pineapple. Another man removed the rind of a watermelon, cigarette dangling from his mouth all the while.

The videos were simple and transfixing. The chopping techniques had evidently become second nature, so practised that they seemed totally casual. The vegetables were unfamiliar, which added to the intrigue. I was hooked. I was convinced enough, by these ten short clips of vegetables being chopped, that I urgently needed more. I clicked through to the profile, hit follow.

At a surface level, the appeal of this kind of work is obvious in the context of the internet. It’s “oddly satisfying”, it’s ASMR, it’s #wanderlust, but it’s also #relatable. Perhaps for these reasons, photographic artist Sam Youkilis has amassed a huge following, and inspires an unusual level of devotion (a comment on one of his posts from December: “Looking at the world through your eyes is the greatest gift I have received. Thank you”). When I look to see what Instagram accounts we have in common, it’s not only photography friends who follow him, but the friends who don’t care about art at all.

Youkilis’s work uses the casual language of the cameraphone, the one with which we are all — photographers and non-photographers — familiar. This, too, part of his appeal; that there’s no barrier for entry, that his style is not abstruse or overadorned or withholding. Though he has a playful, artful eye for visual gimmicks like mirrors, reflections, and frames, his subject matter is the familiar stuff of Instagram, namely travel, leisure, and hospitality. People having fun, people in love, people passing time pleasantly. We watch gruff Neapolitan men playing dominoes and tarocchini, couples kissing on the sidewalk and the beach.

He posts to the grid, but there’s vastly more to be found in his stories, which have the special appeal of the ephemeral. We accompany him through fireside dinners in Umbria and bustling Mexico City markets, watertaxis in Venice, vineyards in the south of France. Yet as stunning as some of the places he finds himself are, though, his work isn’t dependent on exotic contexts. Locked down in New York in 2020, he posted videos of his own baking, soundtracked by the radio in his apartment (“…so the key thing that this virus has taught us, is that the time between when you act and when you see the result of those actions is 2-3 weeks…”); his mom doing home workouts; his empty block. A few weeks later, when restrictions had started lifting a little, friends come to his window, masked, and he pours wine for them, or lowers a basket down filled with desserts (à la the Neapolitan women he documented in Naples); and then he’s out and about again himself, recording the uncanny sight of a man doing Tai Chi, gloved and masked; or the couples that found ways to love each other through PPE. As time passed and restrictions relaxed, he documented suited waiters carrying hand sanitiser to restaurant tables as though they were were under silver cloches.

Youkilis’s work seems to spring from an attitude, a way of being, rather than a particular context in space. It’s as warm and dynamic in the city as in the countryside, on the beach as in the jungle, in the sun as in the rain, during a pandemic as during a holiday, whatever — and this is one of the reasons I feel that his work accesses something deeper and more profound than just being fun and clickable. While in some ways it’s easy to understand the success of his work on a platform like Instagram, I notice just as many ways that his work doesn’t play by the usual rules of online engagement. Many of his videos feel like studies of the kinds of things and people that often go undocumented by photographers: the person who’s not especially photogenic, who perhaps just looks — well, normal. Or, conversely, it’s the subject matter that the serious photographer usually avoids as cliché: the street busker, the sunset, the perfect cappuccino.

While I was working on this newsletter, I was re-reading Jenny Odell’s How To Do Nothing, which isn’t exactly a self-help book in the way that the title might suggest. Odell describes the effects of the attention economy, and ways that we might train ourselves to resist it. She draws persuasive links between our attention and our will: if we have no control over our attention, our control over our desires — including the desire to live in a certain way — is equally corrupted. She examines the work of various philosophers and artists whose work has, some way or other, refused the terms of the corrosive status quo. One of these artists is David Hockney, and his “joiners” — collages of photographs used to distend and transform the environment they depict — such as Pearblossom Highway and The Scrabble Game, and his video installation, Seven Yorkshire Landscapes, in which a grid of monitors displayed the view of eighteen different cameras which were fixed to Hockney’s car as he drove slowly down a lane in Yorkshire. In these works, Hockney was using photographs and video in a way that he believed was closer to the way that we look, just as Cubism aimed to do with painting; at the same time, displaying these partial and conjoined records of a scene made the usually smooth way we join our broken-up looking seem disjointed and strange, requiring us to look consciously and deliberately. Visitors to the show, writes Odell, went on to pay attention differently: “Hockney’s piece had train them to look in a certain way—a notably slow, broken-up luxuriating in textures.”

“Such an offering,” she continues, “assumes that the familiar and proximate environment is as deserving of this attention, if not more, than those hallowed objects we view in a museum.” I feel that Youkilis is doing something similar. His work invites us to pay closer attention to the ordinary, both on- and offline. In encouraging us to spend a while looking at these apparently random passers-by, he encourages us not only to pay a different kind of attention to his Instagram feed, but also to our own lives.

His work certainly reflects a broader movement towards video on Instagram, one that’s been heavy-handedly pushed by the platform itself. Over the last few years, I’ve noticed more and more photographer friends and colleagues beginning to post short videos to their stories. Little, incidental moments whose motion is part of their charm: light dappling onto a wall in the summer, moving as the trees move; the view from a train window. A photograph wouldn’t suffice, because the texture of this movement is the thing being communicated.

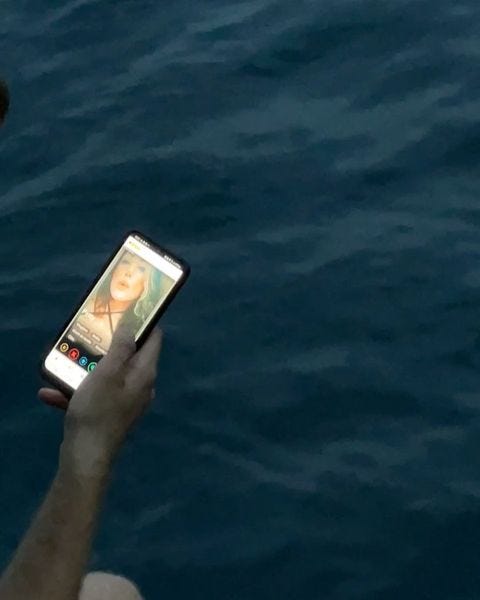

There is a difference, I note, between Youkilis and the way that video is often used by photographers. In the latter group, there’s a coyness, a sense at times that a video is being used to vaguely dangle the photographer’s presence somewhere exciting, a sense that this is BTS (with the real content being produced offscreen), a gesture towards the life of the photographer whilst concealing all the fine details; it’s artful, discreet. Youkilis himself, by contrast, is decisively present in his work: we often see his hands, holding an ice cream or an oozing sandwich. This presence is important — he’s the avatar through which we enjoy these meals, this conviviality. Self-effacement just wouldn’t work: it’s as if these videos, so concerned with pleasure and the texture of things, require a human presence in order to drive home their sensuousness. Sometimes we hear his voice speaking to the people he’s filming; that’s another thing, the presence of sound, the messiness of which is usually coyly removed from other photographers’ artful B-roll.

I think this messiness is part of the reason why the work is special. Instagram is very good at algorithmic smoothing. The internet likes to be a clean, well-lit space, just as our cities and public spaces increasingly tend towards the minimalistic; the inoffensive; smoothed corners, blond wood. This is, of course, in contrast to the realities of being human, and the world more generally — a reaction against it, an attempt to hold different kinds of chaos in check. Odell again:

“This is real. Your eyes reading this text, your hands, your breath, the time of day, the place where you are reading this — these things are real. I’m real too. I am not an avatar, a set of preferences, or some smooth cognitive force; I’m lumpy and porous, I’m an animal, I hurt sometimes, and I’m different one day to the next.”

How to Do Nothing explores the ways that the human experience is vague and strange and inassimilable. In a similar way, Youkilis’s work offers more friction than the usually legible matter of Instagram’s most widely-circulated work.

First of all, the work requires patience: we are invited to watch normal people doing normal things for 15 seconds or more. It asks us for our time. This is no small thing, because Youkilis’s videos don’t tend to have any narrative arc or particular payoff. Often their duration — without satisfying denouement or “wait for it…” tension — is exactly the point. In one video, we watch a middle-aged couple position and reposition themselves for a selfie. The man is frustrated, first at not being able to get the angle, then at his partner’s interventions, the way she points at how he might use his phone differently. He bats her away, then relents. They cluster round the phone together, adjusting settings. Composition finally arranged, the couple adopt smiles, which bloom and wither and bloom again as more annoyances surface and are solved. The scene is completely familiar, though we might not usually permit ourselves the time, nor have the boldness, to observe for so long. We are watching for the pleasure of watching, and we trust Youkilis as the steward of our attention, pointing us towards normal life as it unfolds.

There are strangenesses and idiosyncrasies that can only be revealed in motion, as time passes: gestures of love, for example, or anxiety. The ways that people fidget; the chemistry of personhood that only exists in seeing the way a person moves. Youkilis has made a series of posts showing Italians talking on the phone, with their swagger and emphasis and unmistakeable gesticulating — and how reduced these photos would be without seeing them unfold through time, seeing them dance themselves out as a person walks through a Neapolitan street, incensed.

Where elsewhere the algorithm seems to favour images that show a glossy kind of lifestyle capitalism, Youkilis’s immensely popular work refuses these terms. This is another of its frictions. He travels a lot, certainly, and seems to do plenty of glamorous things. But wherever he finds himself, the people, places, and food he documents are generally cheap, accessible, straightforward pleasures. Bread, olive oil, coffee, ice cream; a good drink poured well into a cold glass. He shows the absurdly precise and still somehow casual skill of local artisans making tacos, or candles, or bagging honey; drawing out the way that a paper plate of street food’s charm and deliciousness comes from the speed and seeming insouciance of its preparation, taking us through each step of the process, and then showing the final result before, we presume, eating it himself. His own enjoyment is obvious.

It’s not just food; he’s attentive to so many of life’s inexpensive pleasures. I love his carousels of loving gestures, people making out in the street, or tenderly holding hands in the subway; an old couple caressing on a bench. Instead of the supposedly aspirational content that Instagram usually pushes so hard, Youkilis shows us people enjoying life for free. Singing and dancing, good or interesting weather, a beautiful sky. From time to time, there’s a person singing, and they’re not a professional or a performer, but just a person he’s with, enjoying singing for the sake of it. Quite frankly, videos like that make me glad to be alive.

The moment, its movement, its texture, its feeling; those are the matter of his work, not photogenic people in luxurious settings. The world he shows me feels like the world many of us could access if our priority was pleasure, was having a good time — and why shouldn’t that be the priority? Why shouldn’t the mere experience of life, as Odell puts it— as opposed to acquiring more, earning more, being richer, being somewhere more exclusive — be the most important goal?

“Gathering all this together, what I’m suggesting is that we take a protective stance toward ourselves, each other, and whatever is left of what makes us human — including the alliances that sustain and surprise us. I’m suggesting we protect our spaces and our time for non-instrumental, noncommercial activity and thought, for maintenance, for care, for conviviality.”

In her introduction to How To Do Nothing, Odell makes a point about the attention economy’s reliance on fear and anxiety, and it’s easy — if you spend much time on social media — to see only the badness and brokenness of the world, to feel constantly afraid. Youkilis’s video works are a little hint of an alternative view — that though there’s much to be afraid of in the world, there’s much joy to be found here, too.

“How endlessly strange reality is when we look at it rather than through it,” she writes. The world, as recorded by Sam Youkilis, is strange, and funny, and staggeringly beautiful. The good things and people persist despite the doom that will never let up. The planet is warming, but there are waiters pushing trays of desserts through Venetian restaurants ankle-deep in water; there are people singing opera from their pandemic isolation, or pouring wine from their windows, or lowering baskets of homemade cakes. Youkilis is a bon viveur, an Epicurean, “holding happiness and leisurely contemplation to be the loftiest goals in life”. Why shouldn’t that be our own philosophy, at least as long as we’re looking at his work? Being pointed in the direction of these things can train the viewer to see and encounter a stranger, more endless world too.

*The title of this newsletter was taken from a comment by @sirensays on Youkilis’s Instagram post from 22nd December 2022.

Thank you so much for reading! I’d love to know what you think about Sam Youkilis’s work. Let me know below:

And if you enjoyed this essay, please share it — it really helps get the word out.

I loved everything about this. Brilliant

I love this essay ! Life-affirming & encouraging, and very beautifully written. Thank you !