Last week I went to see Portraits to Dream In, the new exhibition of works by Julia Margaret Cameron and Francesca Woodman at the National Portrait Gallery. I love both of these artists, but I was preemptively irritated by the way the show is framed by its title — it seemed twee, like a feminised gloss on the aspect of these photographers’ works that is challenging, frictive, especially Woodman’s; and perhaps it also feels, at the moment, like no time for dreaming.

As it happened, I found myself as transported by the work as I always am with Woodman and Cameron, and the curation was sensitive and interesting — the light dim, the atmosphere hushed, and the works arranged non-chronologically, instead paired image-by-image around the two artists’ shared themes of angels, rituals, myth. All the works are contemporaneous prints made by the artists themselves, which made the whole show feel very precious; and I was especially excited by seeing works I was unfamiliar with, like Woodman’s large caryatids, and her pictures of men. I found that the spikiness I treasure in both artists was still there, needling at me as it always does.

Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographs have had a considerable influence on my approach to portraiture — I see her work in my classical inclination, my interest in portraying ambiguous psychological states. Woodman, by contrast, was one of the first photographers that made me understand what photography is capable of. I learned quite quickly that my work would be nothing like hers, but her photographs made many things feel possible for me, potentialities that I’m still trying, all the time, to edge closer towards.

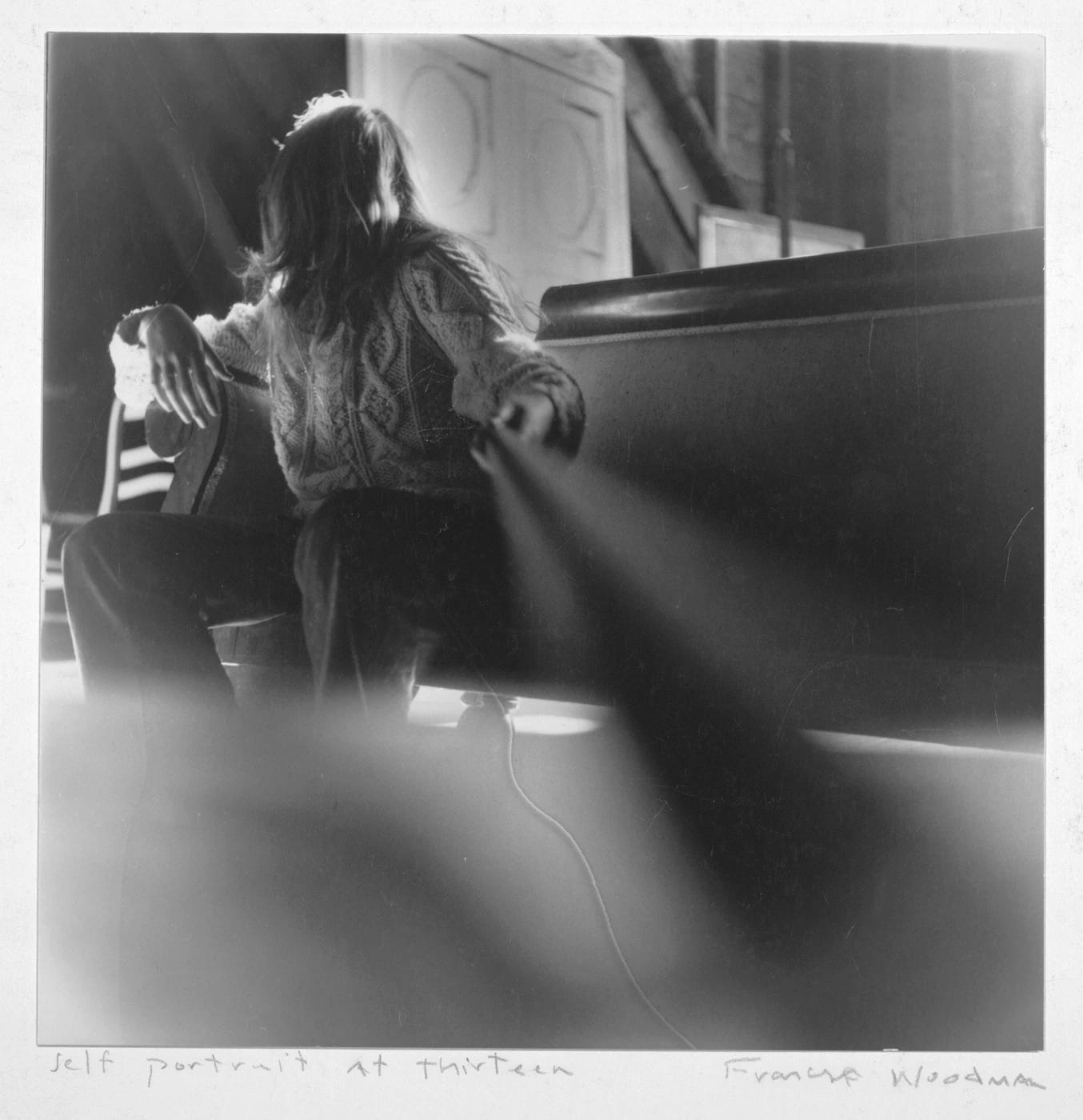

With Woodman on my mind, this month I’ve decided to revisit an article I wrote for Elephant Magazine in 2021, about the picture of hers that set me on my way as a photographer, and that is currently hanging in the NPG. I highly recommend a visit to see it — the small 1970s handprint annotated in Woodman’s unmistakeable pencil script — and the rest of the show, too.

I grew up in photographs. Photography was a bright and vivid proof of life as it is lived, all colour and movement. It was glued into family albums, and it was also my mother’s profession. I lay on the floor surrounded by fairy lights with my brother and sister for a Christmas card picture, and later I lay on the roots of a tree for an art photograph. I didn’t mind, I was a child taking instruction. One day I did mind, and stopped cooperating. I don’t remember this decision, but my refusal is visible in my disappearance from the albums. Just as I’m leaving childhood, I become the back of a head, or occasionally a face baring teeth, furious that I’m there in the picture for a moment again.

Later, I started taking pictures myself — perhaps it was a way of exerting control, putting myself safely on the other side of the lens. At the time, though, it didn’t feel like that; I was drawn to image-making, but it wasn’t an impulse I thought hard about. As a teenager studying literature, my sense of photography was as a comparatively blunt instrument, recording only surfaces where prose could describe the interior. At best, a photographic portrait might show the crudest facts of a person’s split-second experience — grief, pride, longing — but where was the nuance, the temporal? How could the outward appearance of a person or situation get at the heart, the mind, the relentlessness of change?

One winter I met a friend at Victoria Miro, a cold white day on Old Street. I’ll never forget stepping quietly around the gallery and seeing Francesca Woodman’s work for the first time. The prints were small and intense in their velvet greys, and they showed things that I didn’t recognise from reality, nor from the photography I understood as document: figures and forms twisting and elided by long exposure, hidden or distorted by wallpaper and clothes pegs.

In Self Portrait At Thirteen, Woodman uses herself in the frame, but she is turned away from the camera. Her body is a form to use as a kind of graphic element, just as much as the cable from the shutter release. Light frames the back of her head, forms a delicate halo around her exquisitely relaxed hand. It’s a self-portrait, but in her turning away it’s also a self-effacement; a complication of the self, rather than a capturing of something essential.

Looking back at the moment when I saw that image for the first time, I think of my own refusal, my turning away from the camera at a similar age, and the way that Self Portrait At Thirteen countered the belief I held: that you could either turn towards or away from images — that you had to choose. She showed me that the refusal and disappearance itself could be the subject of the work, that an image could be both things at once. As I pursued photography more seriously in the years that followed, I began to wonder what else it could do.

Woodman’s work opens up a space that words can’t access, using the symbols of myth or religion to provoke questions, or induce a restless kind of feeling that can’t be easily described. It reminds me what visual art is capable of more generally: that it can articulate something beyond words. As a teenager this felt revelatory. I had a new sense of the possibilities of photography, the ways it might broaden rather than foreclose the scope of our feeling.

That photograph has continued to exert a subtle influence on both my thinking and my practice in the decade since the first time I saw it. I have started to step cautiously into my personal work, seeing the self as a formal material that can be explored or challenged on the photographic plane. A few years ago, I photographed throughout a phase of family upheaval, eventually making a project about archives and memory, cringing at the self-exposure and vulnerability it required. When I returned to look at it later, it felt both completely authentic and completely separate from me.

In spring I collaborated with another photographer on a series of self-portraits. When the rolls came back, I was amazed to find that they seemed to know things that we didn’t, seemed to indicate something that gestured far beyond the moment of our standing there, dawn light on our backs. The figure I saw in the images felt not like myself, but like a symbol; the photographs described and concentrated a narrative I hadn’t seen or understood even as I participated in it, telling me things about our relationship that I wouldn’t come to fully understand until long afterwards. Such is the potency of the photographic scenario; and Woodman was the first person to demonstrate this to me, the camera’s capacity for the uncanny.

In her final diary entry, Woodman wrote that she was “inventing a language”, and this is how her body of work has come to seem to me. If photography previously felt to me like a proof, here is a work that proves nothing, is form and feeling instead, creating other worlds with all the strangeness of fiction. This is one of the reasons that biographical readings of her work, which focus on her depression and eventual suicide, are so frustrating. Rather than offering clues as to the meaning of her photographs, she believed that her death would leave her work “intact”.

As a reader, I am compelled by the space to the side of fiction where reality and unreality push and pull towards and away from one another. In the decade that has passed since I first saw the show at Victoria Miro, my inclination in photography has become the same; and a medium that seems, on its surface, to depict reality is the ideal one to antagonise and frustrate it. A picture that uses the self but conceals it completely has this tension at its core.

To love Francesca Woodman is a commonplace now; her work has been picked over, analysed, alternately lauded and dismissed at length. But seeing Self Portrait At Thirteen was my first encounter with a photography that played at the borders of fiction and fact, whose relationship to the self was complex and complicating. I see its influence in the work I’ve been most drawn to since, and in the works I am beginning, tentatively, to make. My relationship to it, and to her, is ongoing.

I loved this-- the thoughts on the Woodman show and the thoughts on your own work, which I've never seen. I'll look for it. Thanks for this!

(I wrote on the show last week too, but I came to it from the Cameron side.)

That's nice. I won't hold you to it, I know you're so busy (thankfully). I think it is by appointment only, so let me know or @aniaready? Hope to meet you somewhere sometime! J