Photographing Childhood

"...a time when both language and action were fresh and not yet tired."

This piece of writing was originally commissioned for Emma Hardy’s monograph Permissions (GOST, 2022). I wrote it almost exactly this time last year, so sharing it now feels apt, and I’m glad that more of you will now have the occasion to read it — Permissions is now sold out almost everywhere (last few copies available here). Both text and photographs are generously shared here courtesy of Emma Hardy.

Waiting for a coffee the other day, I watched a girl standing on the path, finishing the last of her cup. Three feet high with a cocked hip. She tipped the last of her drink into her mouth leaning all the way back, turning it totally upside down, then raised it up with a flourish, a high arc, her body elastic, all her gestures the large and shining motions of a showman.

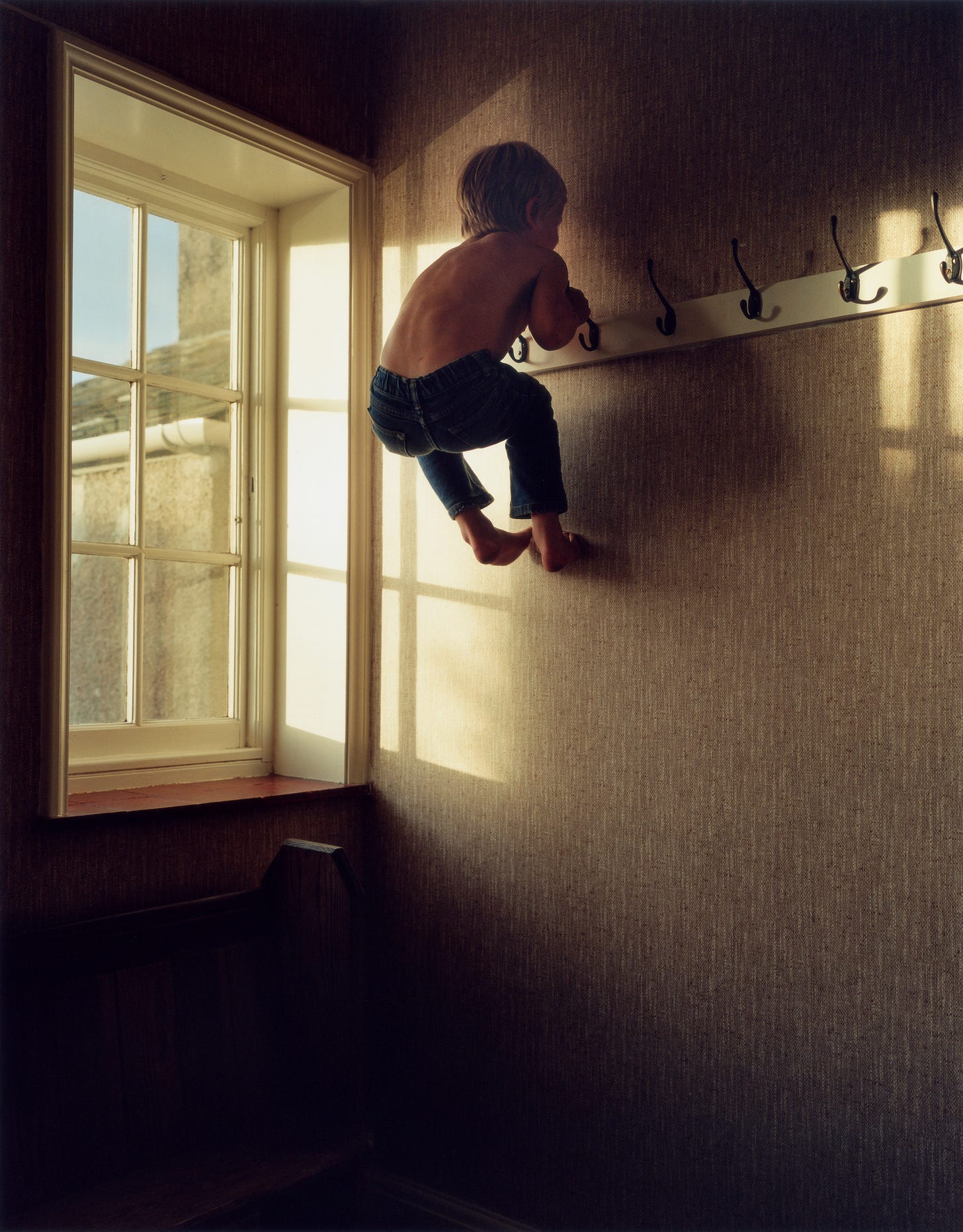

Do you know what I mean? Have you noticed the way that children perform their commonplace activities? To finish a cup, to walk across a lawn: how often those simple movements are exaggerated, made as ostentatious as possible. To learn to do a thing, to do it for one of life’s first times, is to be unnatural in the activity. It is to be a pretender, a performer, as though experimenting with the possible bounds of a gesture, trying it on for size. A showy spontaneity. There is character work to being a person not yet formed, the gestures not yet refined and made one’s own; as though drawing attention to the fact it is new, not yet learned, is a tonic for self-consciousness or naivety. You cannot be accused of ineptitude if it’s all play to begin with.

Still watching the girl, her cup now disposed of, I saw her see a dog. The guise of the showman dropped like a sheet. She crumpled to the height of the animal, looking it in the eye, proffering the back of her hand, the dog nosing towards her gently, quivering, its whiskers brushing her fingers. She looked up to the dog’s owner, asking its name with wonder in her eyes. The movement — from showman to tiny shy admirer — was seamless, the former unselfconsciously cast off without a backwards glance. When her mother called her over and it was time to go, she stood easily and wandered away.

The theatrical gestures are special because they’re for no one. Of course, children like to be watched, and they look to their parents for encouragement, but not all the time. Children playing alone, away from the eyes of adults or even other children, still perform. The girl on the path, for example, was absorbed in her movements, and her mother was elsewhere, distracted. Children’s words are the same: they don’t need to be addressed to anyone, they don’t require a response. Think of the happy chatter of a child narrating an imaginary game to herself — perhaps you remember chattering to yourself like this. And when the games and gestures are finished, they’re discarded simply and forgotten without effort. Childhood was a time when both language and action were fresh and not yet tired. Words hadn’t hooked into their meaning, sentences weren’t worn out and repeated. A time of symbols whose significance was still mysterious, still open to interpretation.

Memories from childhood come in fragments. From a time when I was quite small, I remember saying to myself: I will remember walking along this path. The concrete slabs passing under my feet, the grass that lined the way. I remember walking along the path because I told myself I would. I try to catch hold of the way it felt, but the feeling slips free; it’s only the image and the resolve I remember. I don’t remember the way that gestures felt new. I don’t remember my spontaneous and throwaway performances. These are the observations of an adult, for whom language has put an immoveable blockade between the mind of the present and the mind occupied during childhood. I am an adult speaking to other adults: a child will not read this. Their world is separate.

For the child, the world is not a set of outside structures to be conquered or even explored, but rather something personal and individual, an extension of the child herself. The child is the centre of gravity. The child is the fixed point and the world moves around her, where adults find the world to be fixed, learning the logic of its innumerable interlocking structures and becoming one point moving through it, one point amongst many. Our impact is so small as to be almost nonexistent. For the child, every element of the world that finds its way into her orbit is subject to impact, to vast change. These elements are pliable.

The world brings colours to the child and the child organises them, cuts them into shapes, learns the names of the shapes, speaks them for the first time. Animals, fruits, leaves, water. Wood pigeons outside the window in the summer. Oak leaves brushing old glass. The seasons meaning nothing: just a cold day or a hot one, rain or no rain, being dressed in different clothes. The rush of ducks from their hut to the water in the morning, the rustling rush back in the evening, the nonsense call that makes them come.

Of course, most of these colours and shapes are brought not by the world, abstract and indistinct, but by the mother. The spontaneity and play that are the child’s power, the child’s luxury, are facilitated by her parents, whose effort and presence as such are unnoticed by the child. The child accepts the costume and the props; the child is ferried from place to place. The force of these new impressions is such that the child cannot understand the presence of the mother as facilitator, as director, as world. Like the world, the mother is immanent — something like the water the child is swimming in. Understanding the presence of the mother in the mind of the child is not unlike looking at a family album: one person, the photographer, usually absent, and yet integral not only to the production of the photograph, but also to the scene — to the life — itself.

As I write this in London, in spring, a pigeon is building a nest in the stairwell of my building. A box labelled ‘Danger’, decorated with spikes to deter this very activity, is crowned with a nest of twigs and moss, and a pigeon sits proprietarily on top of it, watching passersby with a black stare. I suppose I’d always thought that a single pigeon would be responsible for building its own nest, but a few days of observation proves this assumption wrong. Standing outside on my balcony, watching the sky in the morning or the afternoon, I see one bird after another fly past me, holding a twig or a scrap of moss or a shred of old plastic to add to the structure. There are numerous birds involved in the project. On Saturday the nest was large and substantial. On Sunday, I left my flat to find a mess on the stairs; children living in the building had, laughing, knocked it down. By Tuesday, there was a new nest, and I watched bird after bird fly back in with new twigs, new materials to build with.

— May 2022

These are beautiful.

Lovely photographs