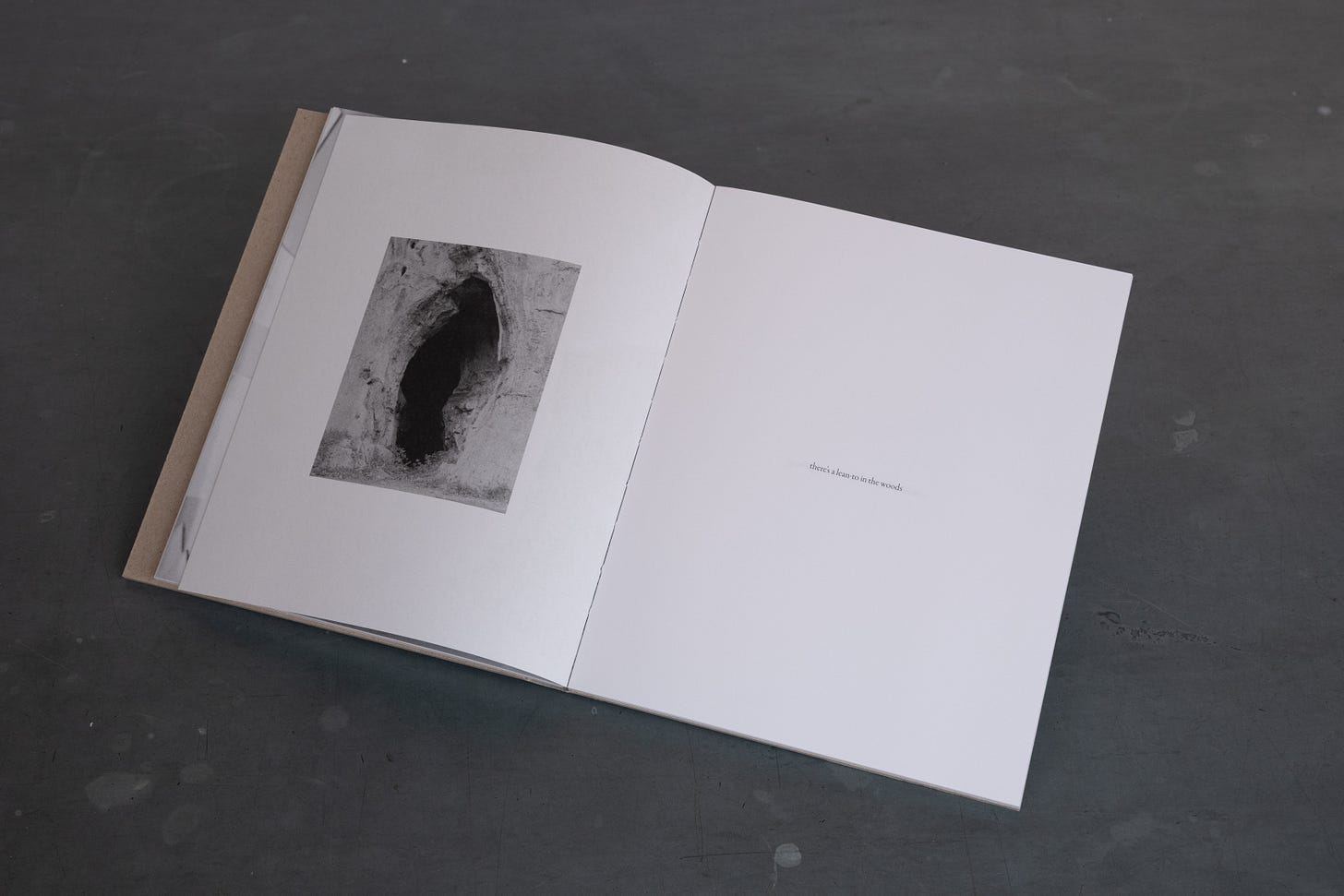

Max Ferguson’s second book, Deadfall, is full of strange voices and scattered narratives of uncertain origin. Published in 2023 by Ferguson’s imprint Oval Press, the “photographic novel” has a haunted, unsteady atmosphere. Biographical details slip into and out of the text; we think we have a foothold before we’re shaken loose again. Where are we — and when? With whom are we speaking? It’s a work framed by the idea of home (ARE YOU COMING HOME, a voice asks at the beginning of the work; I’m coming home another replies at the end) but the narrators seem to find themselves far away from the familiar. They are elsewhere — bewildered, making halting attempts to think and to work, impelled by mysterious forces.

How could I explain that I was here in this small village in rural France because decades earlier a kid in my class had brought in an emperor hawk moth squashed into a jam jar?

Rituals of intoxication are a motif of Ferguson’s work. He pays careful and deliberate attention to the sensuous process of rolling and smoking a spliff, its furls of indigo smoke, its bleached ash, its end glowing orange; the brandy on the table; the memories of the double-stacked Mitsubishis and zoots flicked into the text from the top decks of his narrator’s youth. Often the narrative voice seems suspended at the point just before, or at the moment of, consumption. Whatever comes next — the state that follows the smoke, the drink, the drug — happens elsewhere, leaving its narcotic effect to infuse the pages that follow.

This sense of suspension reflects Deadfall’s general feeling of vertigo. We arrive to the story in medias res, with a dislocation or destabilisation waiting on either side of the words we’re reading, but which never quite arrives. Here we are instead, stilled, inhaling smoke, anticipating the way our felt experience may be about to change. The photographs — quiet and potent — are working their way through delicate membrane and into us.

I wrote to Max — artist, writer, editor, lecturer, publisher, collaborator and friend — via email. We spoke about control and freedom, the split (or not) between image and text, self-exposure, fictions, and working into the not knowing.

Alice Zoo: I’m so glad to have seen the installation of Deadfall — how distinct it felt from the book, as well as your use of unexpected materials: fragile things to print onto, like envelopes, and the frames you built yourself. The tactile is such an important element of your work. Could you tell me about making things yourself, with your hands? Why is that important to you? Is it part of the way you think? What does it make possible for you, what does it teach you, and what effect does it create?

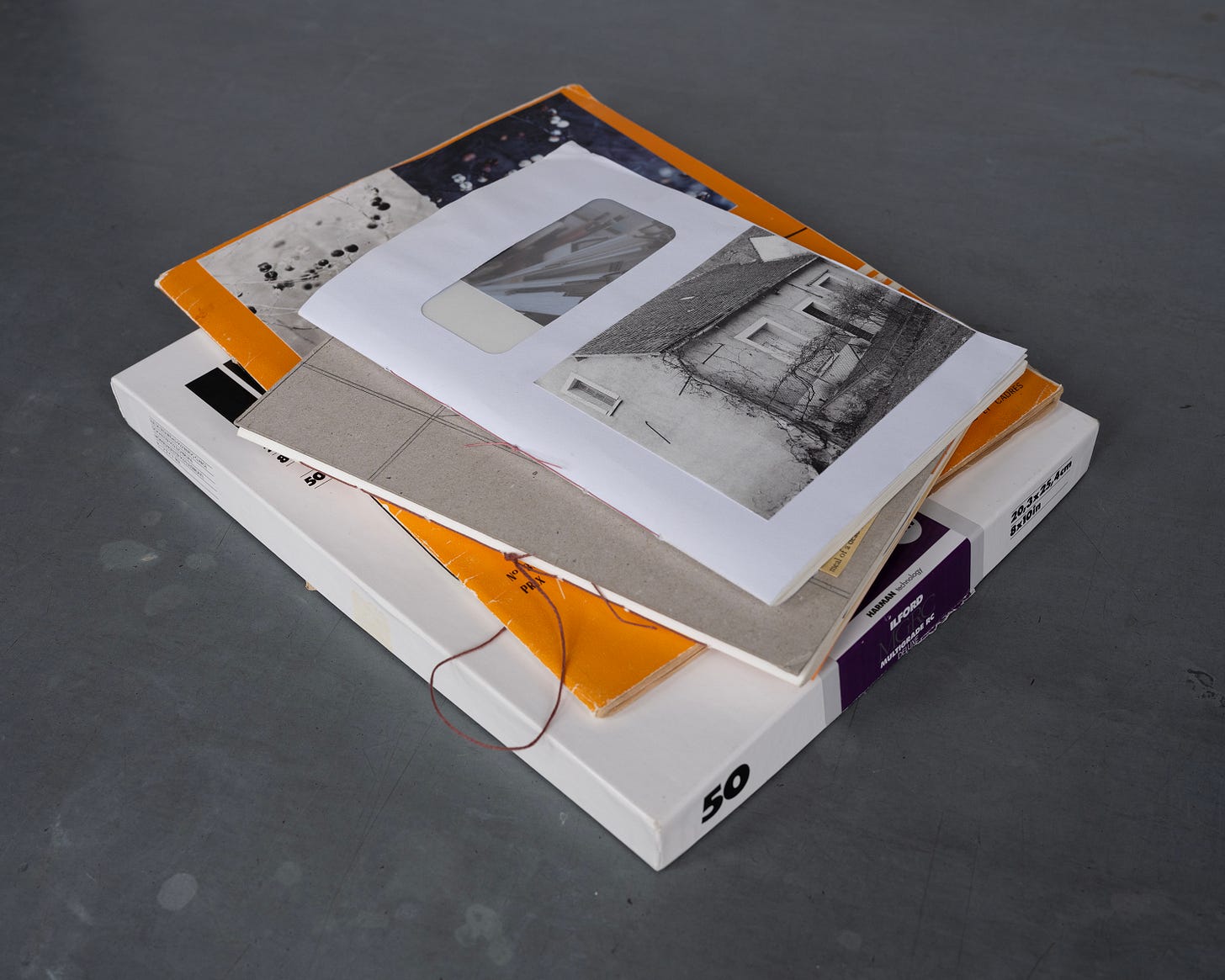

Max Ferguson: I’m so glad you made it to that show, Alice. I had so much fun putting it together, and after two years of working on the book it was nice to share some of the process with people. It’s interesting because most of those fragile things — the envelopes, the sketchbooks, the delicate pieces of paper — were never made to be exhibited. I made hundreds of sketchbooks, prints and zines and the work showed was a small part of the physical experiments. They were research for the book, really — tools to work out the sequence, and the balance of text and image. Almost all of my research is making things and reading fiction — and some other things seep in, of course. I think things often make the most sense when I’m busy making in the darkroom or my studio. It’s where work comes together and the chaos begins to take shape, and the act of making is as integral as making photographs. It’s a break from everything that comes after taking the picture, such as scanning, writing and designing. I made the darkroom prints and the frames specifically for the show, though, and I also framed some of the delicate things in nice wood. Small things such as the the timber or glass you choose for a frame become incredibly important. There is something that I enjoy about treating a laser print with the same respect as a handprint. That can work backwards, too — I sent some friends some silver gelatin prints in the post while I was in one of my making phases. I just wrote their address in Posca marker and put a stamp on the print. I need to challenge myself constantly on the so-called correct way of doing things.

There is another reason I like to make things, though, and it has something to do with control. I don’t like the idea of relying on other people to make the things I want to make. So I publish my own books, make prints, build frames and organise exhibitions. I would, of course, love to collaborate on any of those things, but I don’t ever want to be in a position where my work requires permission to be shown. Having control over these physical, technical and logistical parts of practice is time-consuming but it gives me a huge amount of freedom in my practice. I only have to convince myself something is a good idea, or worthwhile, and then I’m allowed to do it.

AZ: I think a lot about this push-pull between control and experimentation — the way it frees up space within the work, and allows the work to confound or surprise — Rilke’s “living the questions”, Keats’ negative capability. I remember you posting some images on Instagram recently — I can’t find them now — and in the caption you wrote something like “two pictures from Deadfall I still don’t understand at all”. I find that space of non-understanding very exciting to interact with in the work of others, but almost unbearable in the context of my own. But then often the pictures of mine that I don’t understand, or can’t get the measure of, are the ones others seem to respond to most strongly.

I wrote about this a bit here, but I sometimes find that part of my task as I relate to my work is accepting it as it wants to be, not how I wish it was. I’m wondering whether you ever feel similarly. I remember, for example, being so frustrated when I started out that I couldn’t make pictures like Anders Petersen — my work will never look like his, it just won’t come out that way (though I'm actually glad of this now, in the case of Petersen at least). Does your work ever seem to have its own character, with its own motivations? And if so, does that character ever seem to defy you? Do you ever wish it were different?

MF: Ah, I’m sure that the work takes over. And it always defies me. You have to wrestle with it and drag it into a shape normal enough to show to people and that seems to take years. You have to learn about it, how it lives, how to tame it. There are a lot of ideas in my head that I’m losing that fight with at the moment. I guess we’ll see who tires first.

With pictures, I’m very comfortable with losing control. I print with chaotic settings in the darkroom, often playing with the cyan dial; I love the unpredictability of laser printing; I barely adjust the colours on scans and I never dust-spot anything. Recently I’ve been enjoying shooting digitally, for the first time, and it’s hard to bring that chaos into such a perfect system. Maybe all of that is the work taking over though. Guiding me. I like that idea a lot. Maybe it’s more than a character, though, and — as I said — I find my control in other places.

I’m always amazed when people write or talk to me about my work, because they often seem to understand it — better than me, sometimes. People seem to be able to see things I’ve put into it, even when it’s unsaid. Maybe it’s not my job to understand my own work. I don’t think I’ve ever really understood a photograph; not any I’ve taken, anyway. I have photographs framed in my flat by other artists that I look at every day and that still baffle me. I’ve spent the past fifteen years studying, thinking about, editing, teaching and writing on photography, and I’m more confused than ever. I don’t know what makes a good picture. Sometimes I don’t even know what a good picture is. But it’s this disorientation that keeps me interested — no, obsessed with photography. I think I’m trying to ask questions when I take pictures. Like, ‘what happens if I do this?’ or ‘How will a piece of oblique text change this sequence of images?’ I’m sure if I had those answers I wouldn’t need to make photographs. It would be time to move on to something else.

AZ: I’m curious about your process around working with text, and how you consider it in relation to what we’ve been discussing around control. In Deadfall, the text takes many different forms, sometimes mysterious and fragmentary, other times lengthy, seeming almost diaristic. Multiple different voices seem to emerge over the course of the book, different registers and timelines — sometimes the voice is close, clear and specific, anchored to a version of the present alongside the reader, at others it’s mysterious or nostalgic. At one point, the text snakes across the page. It feels like this shifting register is an intensification of the mode you found in Whistling for Owls, which similarly moved between poetic fragments and longer narrative. In Deadfall, more voices are present, the disorientation more pronounced.

How do you identify and transcribe these different voices as you write? How do you go about editing — choosing which text makes it into the work, and where? And could you describe the experience of putting these texts into conversation with your images, and how that changes the nature of each?

MF: I write a lot on my phone. In notebooks too. But mostly I only have my phone with me when I think of something to write down. I guess it’s similar to taking pictures for me but instead of recording things I see it’s usually things I remember or imagine. For Deadfall it was two years of writing and making pictures — but I could only shoot in winter, so there was a lot of time for writing. Some of the longer texts were written on a laptop. Does that make them more serious? A couple of paragraphs came very late into Deadfall. Once I had everything almost finished I knew what was missing. The photographs I want to make leave gaps in understanding. They’re intentionally very loose and writing allows me to fill in some of those gaps, or to widen them further. In some ways Deadfall is a development on what I started experimenting with for Whistling for Owls, but in other ways they feel miles apart. In Whistling for Owls there are people in the photographs so the people in the writing may or may not be the same people you can see in the book, but in Deadfall there are no portraits. You never see the people I talk about or to in the writing, so it’s up to you to decide who they are.

Sebald — someone whose books we both love — talks about using a literary sleight of hand in his writing. The photographs he puts alongside his texts add authenticity to the mostly true things he writes but the existence of lies in his works makes the viewer question everything. I used to think I was doing Sebald in reverse. I wanted my oblique texts to make people question the legitimacy of the images. There’s still something to that but it’s not how I think about it anymore. I try not to think too much about any of the reasons why I do things; it’s more fun just to make things and see what happens. All of that intention is probably somewhere in there anyway.

I find writing hard and it feels more exposing than taking pictures. Maybe that’s why I lean into different voices: to camouflage my own. I can’t tell you exactly what links the narrative of Deadfall. It’s certainly not time or a narrative arc, but there is some order to the disorientation. That’s the fun of editing for me — collecting fragments and bringing random things together. That’s something else I stole from a hundred better writers. It’s like supergluing a shattered bowl back together but all the pieces are from different plates and mugs. Is that just editing? It’s a lot of trial and error. I made Whistling for Owls while I was doing my Masters, and had so much help from tutors and classmates, and I showed a lot of people I respected. Amak Mahmoodian was one of my tutors — I learned more than I can say from her about how to put text and photographs together. But I didn’t show the sequence of Deadfall to many people. There was too much loneliness in the book. I wasn’t completely alone, though, and I always show things to Hannah, my girlfriend. And Brodie Crellin, who I work with at Granta, edited the text once it was almost finished. It’s because of them that the book is finished.

You write more than me, and I think of your photography sitting somewhere within literature and photography — maybe because we talk so often about reading. But mostly you keep your text and images separate. Are you never tempted to weave the two of them together? I wonder if they’re separate for you but entwined for me.

AZ: I have actually worked on three projects in text and image in the past, two book-length and one a visual essay, and I’m working on another longer one now. None of those works have been formally published, though, and they don’t exist anywhere online, which makes it seem like they don’t exist. As I write this to you, I’m wondering why I’ve held them back. I think the answer is, in part, a pragmatic one: that at the moment I make my living from working as a photographer on commission — as opposed to as an artist — and it feels like these quieter, more ambiguous projects might confuse or even repel potential commissioners. Perhaps it’s also a defensive move on my part; that I’m comfortable sharing works that are shinier and more legible, but worry about how these other works would be received, or how they would reflect on whatever public professional identity I have. They feel more personal and more vulnerable, so I can imagine a part of me wishes to protect them.

All that said — photography and writing do often feel frustratingly separate to me. I think I’ve split them in a way that’s unhelpful. Maybe this, too, is why I’ve held back the works I’ve made that do both. I find bringing them together very difficult, very confronting, even if the eventual work does satisfy me. I remember you saying or posting something once about image and text respectively representing feeling and thinking, and that really resonated. Of course those things exist on a continuum, but I live so much in my head that feeling/photographing is very mysterious to me, and I don’t know how to easily integrate them with thinking/writing. Of course, as we’ve seen, not knowing shouldn’t be a barrier to making work, and can actually be a point of departure. I wish I were more comfortable with that.

I’m curious about what you said above — that it’s “certainly not time” that produces the narrative of Deadfall — because I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways that time is addressed in your work. Your texts often reflect and reminisce, have a nostalgic element, or a kind of temporal remove, and the photographs seem to depict a place outside time — nothing in bloom or in progress, but instead rust, overgrowth, leaves grown crisp. Houses and vehicles turned to shells. I understand that you don’t arrange or edit according to a chronology, but time feels like a major theme of yours — I think of the environments and atmospheres you create as somehow after time, as if time has ended and your work is the aftermath. Does that make sense to you? Could you tell me more about how your work thinks about time?

MF: Why is it reassuring to hear about other people's anxieties? We don’t share them with each other enough. I see you as particularly precise and confident with both the camera and the keyboard. Making work on commission is so difficult, so I get the hesitation to damage that important part of your practice and career — although I suspect it might not be as much of a hindrance as you think. The teacher in me wants to challenge you to show more of that work. Since I asked you that question I’ve been thinking about the features you’ve done for BJP where you photographed and interviewed people, so maybe it’s all entwined anyway. I realised a long time ago I’m more comfortable commissioning photography than working on assignments. I’m lucky I make a living from teaching and being a photo editor — but then I don’t have enough time to make work.

Some of my unused phone notes are (clichéd) dystopia. I played with the idea that Deadfall was some event that had wiped out humanity — or at least some of it. The despair turned out to be more internalised than that and I never really used that idea, but it’s in there somewhere. And yeah — time — there is a lot of that in my work. I’m reading Mark Fisher for the first time and there is hauntology in Deadfall somewhere — although I didn’t know that word while I was making it. The past is so present in the work, but I struggle with the saccharine sheen of nostalgia. I think it’s always dangerous when you shoot on film as well. I think that’s where the horror comes in. The ghosts of the past, as Fisher would say. Buildings, cars and scrap are left to decay. Piles of breeze blocks forgotten about. And all the time the forest is waiting to take it back.

Every month I ask each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue.

Max Ferguson’s recommended reading:

A Month in Siena — Hisham Matar

The Peregrine — J. A. Baker

Trilogy: The Notebook, The Proof, The Third Lie — Ágota Kristóf

Grievers — adrienne maree brown

Grove — Esther Kinsky

The Blind Owl — Sadegh Hedayat

A huge thanks to Max Ferguson, and to you for reading. You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below:

I would love to read more on hauntology in photography. Ghosts of My Life is an important book to me, and I have long wondered how to explore Fisher's concept photographically.

Excellent conversation. Excellent writing!