A Conversation with Amak Mahmoodian

"The art shadows your life, and that shadow will be a shadow of comfort."

In Amak Mahmoodian’s most recent work, the forthcoming One Hundred and Twenty Minutes, dreams are translated into images. Arising from a period of time in 2017 when Mahmoodian was having recurring dreams of her native Iran, and while news coverage of anti-immigration policy was particularly intense — “lives and identities reduced to numbers” — the multidisciplinary artist began to work with sixteen people living in exile in the UK, each of whom shared their dreams with her over the course of many long-term conversations.

All of Mahmoodian’s works are based on research, and for this project she eventually spent six years learning about the science of dreams, examining the relationship of Rapid Eye Movement to imagination and memory, as well as the mythic and cultural importance of dreams through time — the different ways that philosophers and artists have tried to understand the spontaneous nightly creation of a private, autonomous world. The images in One Hundred and Twenty Minutes follow a kind of dream logic, simple-seeming symbols — eyes, windows, mirrors, hands, snakes — hovering above a limitless depth.

Born in Shiraz, Iran, and living in Bristol, Mahmoodian’s work is shaped by the experience of exile and displacement from home. This has been her experience here in the UK, after she was advised not to return to her native Iran following the publication of her work Shenasnameh, as well as her experience of childhood. The artist was born a year after the beginning of the Iranian Revolution and her father was imprisoned when she was a child; her family were subsequently exiled to the mountains bordering the Caspian sea. “This period of my childhood was lived with the fear of imprisonment, and the ever present shadow of violence,” she says.

In some ways it’s hard to write satisfyingly about Mahmoodian’s artistic project, whose essential character reaches beyond language, and frustrates a craving for clarity and understanding. The simplicity and restraint of her images ask the viewer to look beyond the frame, to ask questions of themselves and their preconceptions. The experience of her work is unmistakably one of absence and distance, but it is also an invitation. “I trust the viewer,” Mahmoodian told me.

We spoke about dreams, exile, artistic refusal, and the sacred potential of activism, via Zoom. Our (much longer) conversation has been condensed.

Alice Zoo: I’d like to start with your most recent work, One Hundred and Twenty Minutes. Could you tell me how the project began?

Amak Mahmoodian: The title of the project, One Hundred and Twenty Minutes, is the amount of time we dedicate to dreaming. Every night, every single person dreams for two hours. Some might remember their dreams and some might not, depending on personal experience; but that is the length of time that we’re living in a private world that we are creating. And this project, similar to all the projects that I work on, was deeply personal. It related to recurring dreams that I had about home, beginning in 2017. After that I became quite interested in the myth of dreams, and also the science of dreams.

Living in exile now for fourteen years, there are times that I feel quite hopeful — I feel there may be a time to return, I feel the connection — and there are times that I feel quite hopeless. And I wonder if there will ever be a time or an opportunity for me, after fourteen years, to go back to the roots that remain in Iran.

So I decided to focus on the dreams of people who live in exile, in situations similar to my own. Very often when someone is displaced, we don’t talk about what remains in their country, what they left behind. This is very often forgotten. And those memories, pasts, families, loved ones, identities, are somehow visualised and reformed through their dreams. I started to work with people living in exile through working with Multistory. I met five people living in Birmingham, in exile from their own countries, and that project was the very first stage, the beginning of the work. But later on, those people started to introduce me to others, and the project was expanded to sixteen people, living in different areas in the UK. They all live in exile, and they are from sixteen different countries, and they talk to me.

One of the reasons that the project was quite long is that dreams are personal, and I respect that. I am forever grateful for the trust that participants had in me. There wasn’t any push to contact them and say tell me your dreams now. Very often it was dialogues, conversation, and then sometimes they gave me their recurring dreams, or sometimes it would be one dream — the one that they could not forget. They told me their dreams, and I constructed them into images, trying to turn the most accurate or significant elements of the dream into pictures, in the hope of creating a new experience — a vision of exile which is understandable for me, as a researcher and photographer who lives in exile; for the participants; and also for the viewers. It doesn’t matter if you live in exile or not; I was creating a universal language to understand the experience of those people.

AZ: Once you had decided to make images of the dreams, how did you go about beginning to make them visible? How did the process begin, how did things start to take shape?

AM: I look at this project as a life experience. It was something that was very much related to my own experience, therefore it wasn’t about any outcome. It wasn’t about finding one final image to convey the message; it was about the process. The process of understanding, sharing, giving, coping, with other people who are living in the same circumstance.

The process was quite active, and it helped me to develop the work, and also to observe and deal with the situation — because part of it was really painful. Towards the end I started to dream their dreams.

And what eventually became the most important element of my work was the sketchbooks of the dreams. By working through sketching, and repeating, and visualising the dreams, I started to understand the elements; and I started to realise and accept that I could not make the dream exactly the way they saw it. We had this conversation together. I could make something which would be the most similar experience for me, and also for viewers of the work.

Therefore the edit of the work was always in conversation with them. I would sketch their dreams in this sketchbook — you have seen the sketches, they are my life, they are always with me — I would sketch, find the elements, take the photographs. We went through the editing process together, and they would choose the image closest to their vision of their dream. That was the way we were working together from the beginning.

AZ: I’d love to hear more about the sketchbooks, and your process of working things out on your studio walls — it’s striking that you work in such a physical, tangible way. It’s very material, which is especially interesting given how often your subject matter is immaterial or abstract. Could you speak about the importance of physicality in the way that you work, and how that informs your process?

AM: The importance of physicality comes through the importance of understanding the collective work. I had to learn how to make videos for this work, I am drawing some of the dreams, I even have to paint some of them. I couldn’t use photography as the only medium for this work. And the physicality comes through this collective experience of working with the participants. The subject matter is not physical — it’s very strongly connected, as I said, to the imagination, to the past.

Through conversation and dialogues with the participants we decided we wanted to create evidence: a body of evidence, a testimony, and a dedication to these people. Therefore I am collecting all the physical evidence that I have from their dreams, from their words, from their visions, in order to create a language which is more understandable for the viewers, without even being in exile, but sharing that experience.

I collect photographs, writings, and everything goes on the wall as evidence, and also as a reminder. Very often, when you are working on projects which are collaborative, I think it’s really important to have this constant reminder that you are one of these elements, and they are all surrounding you. These people are individuals — they have their own identity, and their place on the wall of my studio.

AZ: In having this identity, and their place on the wall, as you say — it makes me think of art, or the making of art, as a kind of anchor or a home, somewhere that’s native to you.

AM: Absolutely. It was really interesting to come towards some writings, some writers I really admire, like Ben Okri, and talk about the portrait: what remains, and how it’s become an anchor, and connection, and the hook to take us back, and again push us forward. It’s just understanding who you are, and what you do, and what your responsibilities are as an artist, or a writer, or a painter, or a human being. Especially these days, in the shadow of what’s happening. Every single step is quite critical. And I don’t want to feed the system, because unfortunately the system is brutal. Very often I don’t want to call myself an activist, but I am really interested in activism. I really respect activists.

I also read about photographs that invite you to see not what is it only in the frame, but that actually invite you to see what is beyond the frame. To look at a photograph is not the end. You don’t go to a gallery, or come to my studio, or look at a photograph to see the end — to see the imagery, framed, shaped. Actually the frame is more like a window, the beginning of understanding beyond that frame — an invitation to understand more. I’m really interested in this while I am working.

AZ: In past interviews you’ve described feeling tired of having to prove yourself as a Persian woman living in the UK. I’ve been thinking about your work with that in mind; the ways that it’s not documentary, but instead it’s questioning, it’s mysterious. I was thinking about the ways your work refuses the demand to prove or demonstrate — how it asks you to think beyond the pictures.

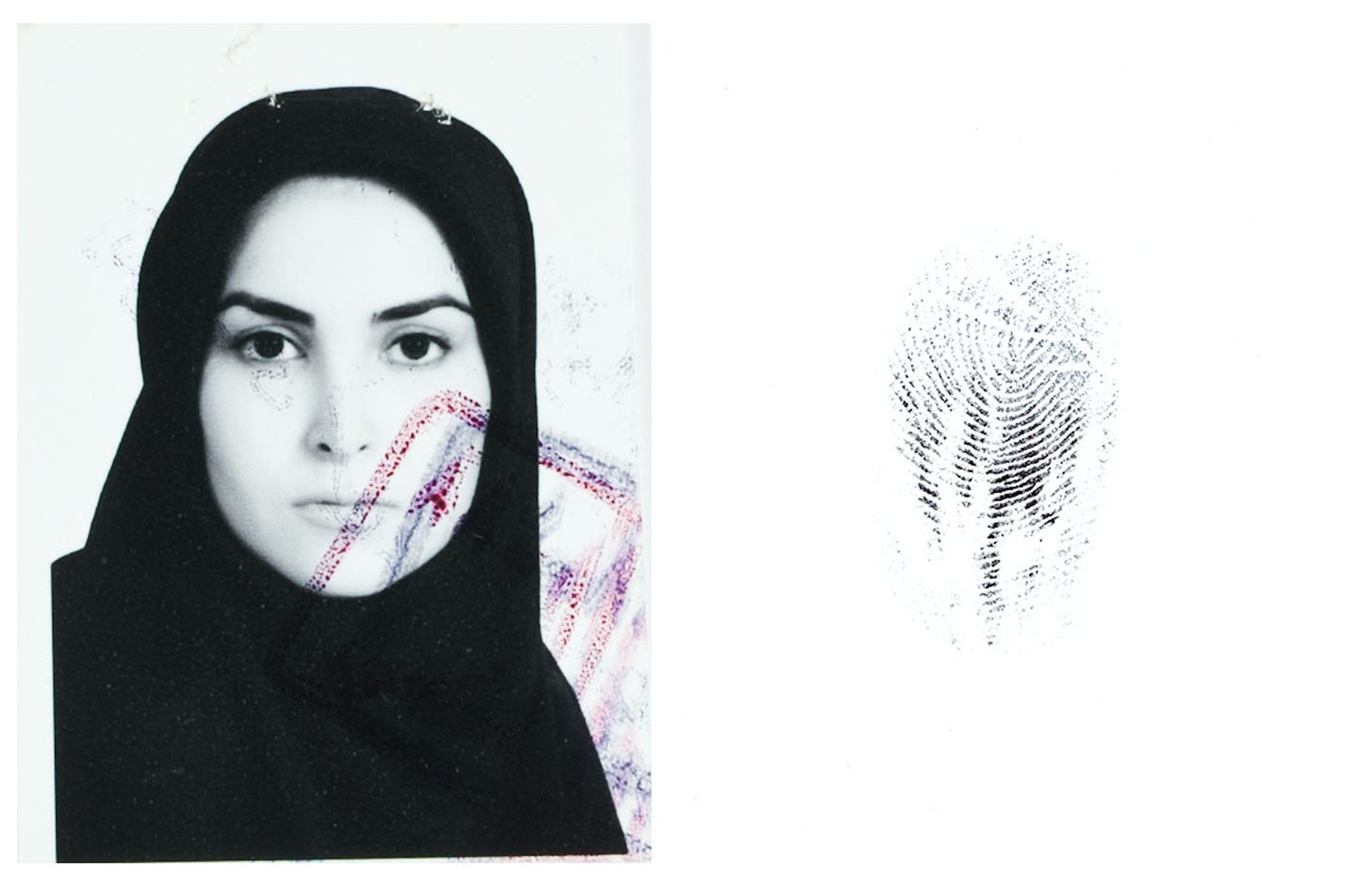

AM: I’m so glad you mentioned this, because this is what I’m really trying to achieve through all these chapters of work. The world makes us angry, and we are all angry, screaming, shouting; it could be related to social issues, or it could be related to our gender identity. We are all fighting, we are surviving, which I really respect about every single human being these days. Everything is political now, especially looking at children, and the next generation: you cannot divide your work from politics. But what I’m trying to achieve, and to present and explore through the work, is not to shout it. Even my Shenasnameh is quite quiet. It’s a work of protest. It’s a reminder of females in Iran and their fight for 40 years against the dictatorship, and against the Islamic regime.

Instead of having very clear language within the photograph, I love to go through the quiet moments. I trust the viewers, and I want to invite them to come closer and look with different eyes, without any preconception, without any stereotypes, without any influence from the media. Then you stand in front of that fingerprint, and see what you see — rather than showing the person shouting in the street, or showing something full of blood, or colours. Because I’m thinking: what if we invite the viewers through the quiet, more thoughtful moments, which become like a bridge, bridging their lives to those lives. I did this with Zanjir too; talking about quiet moments of concealing the face in hope of revealing the identity.

And the same with dreams. Of course we read about violence, and anger, and the reduction of real identities, every day on our phones, from morning til night. And right now it’s happening more and more because of those in Palestine, or Ukraine, or Lebanon. But the dream is something which creates a private world to pull you in, into this wonderland of the past and imagination. They create this bridge, and make you feel closer to the real experience: the inner state. The outer state is related to political leaders and their decisions, and we are not part of that. I am interested in the inner state of my participants. That creates the quietness and calmness through the work.

AZ: It’s interesting that you don’t identify as an activist, given that you describe Shenasnameh as a work of protest — and after which you were advised not to return to Iran. Your commitment to your work has led to extreme consequences. For me and most photographers I know, it’s a real luxury to practise however we wish without fear that we’re risking our freedom.

Your work does feel at least related to activism, in the sense that the personal risk or the stakes of making it are so high. What happens to art when its consequences spread out into the whole of a life, for example leading to exile?

AM: It feels like a shadow. The art shadows your life, and that shadow will be a shadow of comfort. Art has so many different meanings for different artists, in terms of the context of the place they live in. And for me, I was really grateful for the uprising that happened last year in Iran, because it was clear, and obvious, and visible to everyone because of social media. The Woman Life Freedom uprising was evidence of the silent protest that has been happening in Iran for decades.

As an artist you make a decision; it depends on what art means to you. And for me, there’s no separation between me, my identity, my life and my work, because my work is a narrative of my life. They are embedded within each other, and connected to each other. And as a person you cannot turn a blind eye towards reality. As a person who is dealing with the pain of people, and their struggles, and their bravery, they are hopeful and they are powerful; and that is something which we can see, and we have witnessed… Therefore it gives you a sort of responsibility, when you have the opportunity to speak with them, and for them, to become the speaker, not the voice — because they have the loudest voice, and they don’t need my voice. My voice is nothing compared to them.

Because of the dictatorship, because of the Islamic regime, the platform [in Iran] is not as free as it is here. But on the other hand, it is a choice. And through the work I decided to talk about the reality of my people, and the reality of my people is something which has been censored. The regime don’t want it to be seen by others. It was risky, because I was talking about Iran in a Western country. I had a different context, and I had a different audience. And because of the preconceptions, because of the stereotypes, I always had this fear of being misunderstood, that the work would become misinterpreted, or be translated in the wrong way.

As an artist you cannot control everything, but you can create a bridge, a language; so that was what I tried to do. But on the other hand, in your own state, they don’t want you to talk about reality. I somehow knew what the result of that would be, and I wasn’t scared 11 years ago; but now there are these confusions in my head. There are days that I cannot even leave this room; and there are days that I feel the power is in my veins. So that is the price.

Maybe one of the reasons I don’t call myself an activist is because it’s a holy word for me. I think the real activists are, for example, the participants in my work, because they allow the collaboration. If they decide not to tell me their dreams, I’m nothing. Those people, with those very strong, powerful stories — they are the real ones, they are the real activists. To stand there and tell me their stories and make it possible for me to make this work.

AZ: And then you’re the one that’s bridging the distance between the activist and the viewer — or the past and the present, the inner and the outer. I’ve thinking a lot about your use of mixed media: you’re writing poetry, and taking photographs, and making films, and working into sketchbooks. I’m wondering whether you think of each of these mediums differently, or whether they exist on a continuum of materials for creating bridges.

AM: It’s great actually, the way you describe that, because building a physical bridge, when you want to bring two sides of the river together, you use different materials. You just want it to work, and to be safe, and to bring truth to the people. You don’t want somebody to step on it and fall into the river. As an artist, I don’t want to limit myself to one idea, or one medium, especially with research-based works.

Through the research, through the process, you learn that perhaps I can use these different materials to create a more understandable language, or a universal language, rather than limit myself to this specific medium. And that is what I try to understand through the research for each work, understanding what would be the most truthful approach for the audience, and also for the participants of the work. When you work with communities, the ethical aspect is above everything else. Therefore whatever makes the elements of the process — the narrative, the story, the identity of the participants, their past, their present — more understandable, and more clear for the audience, I use it. It could be film, it could be painting, it could be photographs, or I turn to my words, and use words to create something that I don’t know how to make within an image. All these materials come together. I use poems, archives, paintings, drawings, sketches, films, but I never separate them. I see them as one element, which are the materials of creating my language, and creating the outcome.

AZ: I’m curious to know more about the presence of poetry in your life.

AM: Part of it is cultural, because the Persian language is quite poetic. It is really hard to translate, because, for example, for the word ‘love’ — we have 17 different words to describe different levels of love, and so I’m thinking which love is this one, how can I explain it? So part of it is related to the poetic approach which we have in our language, and Persian culture, and the historical and mythical epic writings, and poems and poets who were in Iran for centuries.

And another part of it is related to my family, because poetry was the element that could bring my family together. We would get together, sit together — it didn’t matter whether they were good days, hard days, difficult days, happy days — and read poetry together. We were all reading Hafiz. And it was the language that we used as our love letters. Even now, when my mum wants to write something for me she writes a poem. It shows a poetic connection.

And that is one of the reasons I use it in my work, and as I said, sometimes living here [in the UK] it is hard to create photographs related to my past. It is difficult to visualise them, because although you know within what you want to achieve, outside you cannot see it in the way you want. And so I prefer to construct them through words, rather than images and photographs.

AZ: What language do you write poetry in? Or is it across languages?

AM: I write in Persian too, but for the projects I write in English because of the limitations of translation, and because the work will be seen in this context. But then often I write in Persian; and for the final pieces, I write in English and then translate into Persian.

AZ: Do you believe that people have a different soul in a different language?

AM: Yes. Because you create that soul. And it’s the beliefs and the memories within each word. Even within your own small family, there might be a few words that are really common words for me, but maybe they are very special for you, because for instance it could have been something between you and your mother. I think that is the power of words. Your personal language, and the language of a nation.

AZ: Yes. And that ties back to this idea of dreams as a transcultural language.

AM: Absolutely.

Every month I ask each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue.

Amak Mahmoodian’s recommended reading:

Sculpting in Time — Andrei Tarkovsky

A Time for New Dreams — Ben Okri

A huge thanks to Amak Mahmoodian, and to you for reading. You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below: