Copeland Gallery is bright and spacious, with panels on the ceilings that let the sunlight through. Last Sunday, when I visited on the closing day of Peckham24, the clouds shifting past the late spring sun overhead suddenly illuminated the walls as I looked, the pictures on them newly glowing.

Back to the Future — the theme of this year’s exhibition, which was open for a full two weeks, rather than the usual weekend — “explores photography’s complicated relationship with history”. Personal histories (the family archive, cultural memory, the self and its inheritances) were the explicit focus, and the collected works spoke intimately to one another on these subjects. As a whole, though, it struck me that the show was equally invested in exploring in the capacities of photography as a medium, how far it can be stretched.

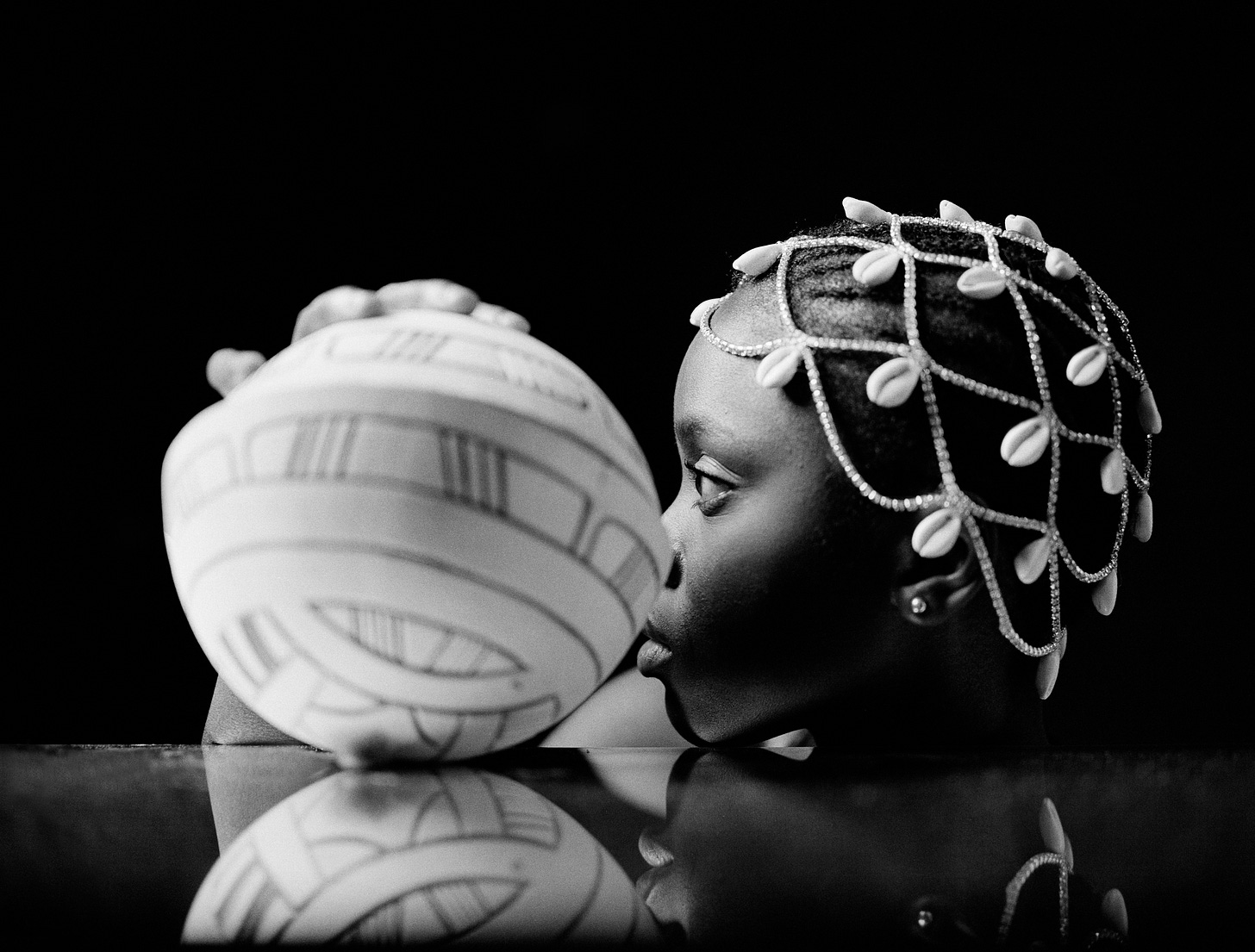

Several works involved the staging of performances. In Orí Inú, Aisha Olamide Seriki photographed figures holding keepsakes and ritual objects from her native Nigeria, alongside sculptures of comb forms (a metaphor for African diasporic “ritualistic empowerment, care and communal bonds”). These objects and their staging — which reminded me of the work of Khadija Saye — allow Seriki to “repair a break between her mind and spirit, and realign her own destiny”.

Emi O’Connell, in and then i ran, made a series of self-portraits dramatising her grandmother’s escape from a mother-and-baby home in Ireland, her blurred and tripping figure connected to the foreground by means of the cable release used to trigger the shutter. Nancy Floyd has been photographing herself every day since 1982, watching herself age and change her context, her friends, her pets; even her methodology has changed over the years, as different work schedules meant she had to photograph herself at different times.

Another of the several artists working with self-portraiture — or at least using the self as one of their materials — was Mia Weiner, whose hand-woven tapestries were another highlight. She weaves photographs of herself and her friends into fabric with pale blue thread, silver running along and through it, the warp and weft flashing in the gallery’s intermittent light. The figures in the works are headless, like Greek statues, made symbolic; the artist used their forms as archetypes to explore mythology, memory, and queerness. Vivienne Gamble, artistic director and co-founder of Peckham24, told me that there was a debate around whether the tapestries constituted photography, which to me is always a sign of exciting work.

My favourite works, as well as those by Seriki and Weiner, were by Tarrah Krajnak, whose photographs in SISMOS79 record still lives made from broken glass, mirrors, light, and pornographic and political magazines from the year she was born; formally beautiful panels with an incendiary core that reminded me of Carolee Schneemann’s Controlled Burnings. Krajnak describes the works as as counter-archival; through them, she pushes against fraught personal and social histories, imagining the transitional moment of post-dictatorship, pre-war late 1970s Lima, from where she was adopted as an infant.

Many of the works were sculptural, or displayed in such a way that they became so — pinned directly to the wall, for example, giving them a fragile immediacy. In one of Alba Zari’s works from her project OCCULT, a photograph is bleached almost into disappearance, a reminder that the photograph, as an object, is transient and impermanent. The raw floors and walls of Copeland Gallery itself are an ideal setting for a show like Back to the Future, and its interest in a self-referential photography whose own materials and means of display become part of the subject of the work, the form just as important as the content.

None of the works was straightforward, the kind of photography-as-document that you can interpret without any prior knowledge, which was part of the point. Each used photography as just a point of departure, working into and onto it to force new capacity from the medium, and each was deepened by reading the accompanying text and learning of the artists’ research, methodology, and context. Staged and presented in such a way, the works and their histories point not only to the medium of photography and its limits, but also to the presence of the photographer herself, a presence that some other kinds of photography seem to hope the viewer will forget.

This photography — its methods, materials, and authorship so visible — becomes a system by which we can learn to look anew at the ordinary things that often pass unnoticed or unscrutinised; or indeed to make visible those immaterial things (cultural history, memory, inheritance) that are so hard to visualise. In Back to the Future photography is not just a document, but also a way of shifting, frustrating, refracting our ways of seeing; holding up mirrors, then breaking them into pieces that catch and multiply and muddle the light.

Lately I often find myself wondering about AI (and this is inevitably invoked by the “future” of the show’s title). How will these new technologies affect my work, the ways I understand images, even my ways of looking and seeing? Will they end the need for photographers altogether? As I have reflected on the works exhibited in Back to the Future, I keep returning to how strikingly and irremediably human they felt in their tactility, their materials, their surfaces; made by hand, over time, with effort and intention. As a viewer, too, it felt important to be physically present with the works, to be a body in the gallery, to see their surfaces under the changing light — and to recognise my own contingency, the histories and identities I was bringing to my looking.

The meaning of these works depends on all these kinds of physical substance, and on their contexts. Memory, archive, intergenerational inheritances — all are intimately interwoven with the subjectivities, contingencies and personal histories of the artist making them. I can’t help but think how limp, how shallow, computer-generated images seem by comparison.

This line got me: “Photography is not just a document, but also a way of shifting, frustrating, refracting our ways of seeing.” That’s exactly how it felt reading this—and imagining the gallery space through your eyes.

What stuck most was your final meditation on tactility. We’re so inundated by frictionless image-making now—AI, auto-enhance, endless scroll—that the works you describe (Seriki, Krajnak, Weiner) feel like rebellion. Not just because of what they depict, but how they insist on materiality. Threads. Bleach. Broken glass. Things that hold time differently.

I’ve been building AI systems trained on my own work, and even at their best, they lack… bruises. Smudges. That sense of soul that arises not just from the final image but from the struggle of making it. Reading this made me long for that friction again. The gallery light. The surprise. The weight of presence.

Thank you for writing this. It reminded me that art is not only seen, but felt through the body.