A Conversation with Siân Davey

Rupture, intuition, and faith: a tarot reading

Siân Davey’s newest work, The Garden, arose from a family crisis. Navigating her way through a harrowing upheaval that would go on to last for two years, she began — in collaboration with her eldest son, Luke — to clear the long-abandoned garden behind her house, planting it according to the cycles of the moon, and filling it with flowers. Neither of them had undertaken a project like this before. “Luke and I obsessively shared our dreams, our insights [...] We called in our ancestors to support and strengthen our vision,” she writes of the process. Their shared intention was to cultivate a space grounded in love. As the flowers bloomed in abundance, sweetpeas climbing tall above poppies and dahlias and gourds, people began to arrive, and Davey photographed them there.

I live close to Davey, and I’ve been spending a lot of time in her garden recently as she makes photographs during the third and final summer of the project. The effect the garden has on people is uncanny — it’s visible in the portraits, of course, the way that so many of Davey’s subjects spontaneously ask to be photographed nude; the variety of people who find their way in; the peace, courage and vulnerability in each gaze — but it’s especially striking to see these encounters happen in real time. When a passer-by stops to admire the garden, telling Davey how beautiful they find it, she asks if they’d like to come in to be photographed there. Invariably they agree immediately, without any further explanation, as though they’re arriving at a long-held appointment. As Luke describes it, seeing the undeniable and profound effect that such an exuberance of natural beauty has on people feels close to miraculous.

Over the past two years, Davey has also been running a series of group workshops called the Creative Body Process. Drawing on her background as a psychotherapist, as well her more recent experience as an artist, and taking place in and around her home in Devon, the workshop acts as an intense creative reset. Davey leads each group through a series of practices of embodiment and uncompromising inner enquiry in order to reconnect each participant with their creativity, and help them to find the narrative purpose that has been lost or dimmed by the pressures and alienation of contemporary living. The workshop is cameraless, and its exact methods remain necessarily shrouded in secrecy. Past participants won’t reveal what happens on the workshop, instead simply encouraging others to do it if they feel called to, and see for themselves.

For full disclosure, Siân is a friend, and we’re both members of a group of photographers called The Emmas, which also includes Lúa Ribeira, Clémentine Schneidermann, Alys Tomlinson, and Abbie Trayler-Smith.

For this conversation, I took inspiration from Alexander Chee’s essay The Querent, part of which was shaped around the drawing of three tarot cards. Siân and I committed to using the tarot as an anchor for our discussion, conducting our conversation as a kind of reading. Siân shuffled the deck and then I spread it out on her kitchen table. She drew three cards, and we turned them over in the order they were drawn.

Alice Zoo: Oh wow, all wands.

Siân Davey: That’s so interesting! It’s all about creativity.

AZ: Golden and gorgeous and shining, every single one.

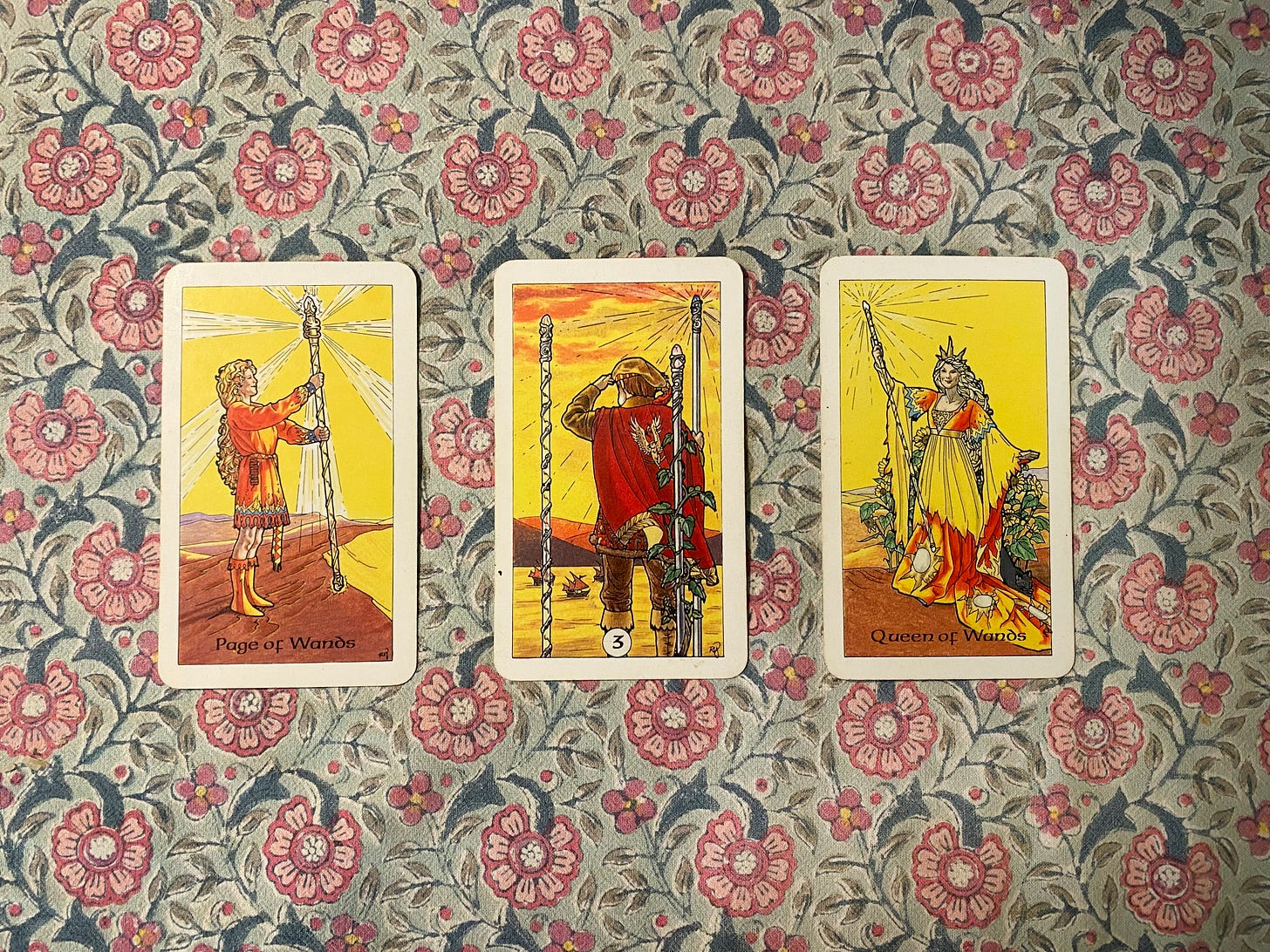

SD: So what is this first card? Page of Wands. It’s the beginning.

SD: That’s what I thought it was — it’s about the birth of a new enterprise, isn’t it. That’s really interesting.

AZ: So maybe we could talk the beginning of photography for you — how it came in, and what was going on then?

SD: Yes. I think I felt almost hijacked, or ambushed. I hadn’t been looking for a significant change in my life at the time. But what’s been constant in my life is the inner work, and I think when you commit to the inner work you get signposted.

This is what happened: I went up to the Tate, from Brighton, for the Louise Bourgeois retrospective. I walked in, and I can remember looking at the work, at those extraordinary mannequins she made, the pink ones sewn together and wrapped around each other, and somewhere it connected to my sexual abuse as a child by my grandfather. And also by my father, the absence of healthy boundaries, how he invaded me.

When I came out of that exhibition, I burst into tears. I felt really quite broken, and said to my partner at the time, “I’ve got to be a creative.” I did my first degree in painting, many years ago, but actually I was never a painter — I’d never considered myself a creative. What happened in that moment was a transmission. I had no idea what it would look like.

And then, two or three years later, I don’t even know why, but I picked up the camera. I rustled together a camera club, me and my mates, to go out taking pictures, only so I could keep saying “how do you do this?” I found a camera that I could stick on auto, and that was it. And then it kept getting magical. I knew that I was being looked after.

Very soon after that, I’d moved to Devon and applied to go on to the Plymouth MA, because I knew I wanted to make my own work. I was working with David Chandler and Jem Southam. On the first day we were in, we were given a different photographer to take home and present in the next session. I didn’t know a single photographer, because I wasn’t a photographer; I’d only taken a few pictures.

The person they gave me was Julia Margaret Cameron. She didn’t begin photography until she was the age that I was at the time, and she had four children like me. I had these shivers up my arm, and I was like: she’s standing next to me, and she’s giving me permission. She’s validating something here for me, that was it. So the magical kept happening.

And then it was a love story. I fell deeply, deeply in love. I’m not entirely sure I’ve ever really felt in love with a partner before, but I had fallen in love with photography. I was off. And it was the perfect beginning. These two women: Louise Bourgeois, Julia Margaret Cameron. And later on, my love for Arbus’s work. I was surrounded by these super cool women who were doing great stuff.

AZ: That’s so funny about Julia Margaret Cameron, because I feel like there are many similarities between you and her.

SD: That’s what Michael Hoppen, who represents my work, has always said. But I don’t study photography — in fact, I rarely look at photography unless I go to an exhibition. You’ll never see me looking at books and online at other people’s work — I have to see the print. Within the print you get the transmission. You get the DNA of the authors, don’t you, in a print. So I’ve never studied her work.

AZ: Can you tell me about moving to Devon?

SD: Some people just see risk, and other people don’t. I don’t see risk. If something pops in, I just say let’s do that — I’ll deal with it later. Sometimes that can be problematic. I said right, in two years we’re going to move the whole family down, and we moved exactly two years later, almost to the day. I was so bereft about not being in amongst concrete, in chaos, in that very low vibration of city life. I always lived equidistant between the police station and the hospital; I was sandwiched in-between the sirens. So I found it very disturbing to have all this space, and this high frequency that you have living out of a city.

Everything was really ruptured, moving here; I was very distraught. But when your boundaries are ruptured it gives rise to possibility. We have no idea, really, of what we are capable of doing. We live in a very limited view of ourselves. So it exploded my boundaries, ruptured them, and when we’re ruptured we need to resolve something quickly. Something needs understanding. And I think photography really facilitated that transition; it helped me understand it. And it also threw up so much about my history around belonging, and connection, alienation; always feeling a bit on the outside. I really was an outsider. I’ve lived as an outsider, and I’ve always challenged what’s around me.

AZ: What you were saying here about rupture, and then suddenly feeling away from the concrete, it reminds me of this scene on the Page of Wands. Do you know what I mean? Because it’s quite stark, as well as being very potent.

SD: Yes. But the Page of Wands is holding this golden wand with this light coming out of the top. That transmission, that signpost, was my light. I had no idea what it was going to look like. I have a very strong faith, and my faith led me, and I had to let everything unravel around me. The dots had to join.

I just stayed open. It’s like: show me what I need to see about my evolution. We lead the world through our thinking mind, and we don’t work so well, in the Western world, in our intuitive body, which is why we struggle as creatives.

It was at this time that I gave birth to Alice. I gave birth to a child with Down’s Syndrome, and at the same time I was really picking up the camera. I left Brighton, and then came here to Devon, and took this enormous risk. I didn’t know anyone, nothing felt familiar, and I’d left my practice as a psychotherapist. But I knew that I could not be encumbered by my past; that I could not stay where I was, just because I had friends. It wasn’t enough. There was an evolution I had to deal with. There was something else I had to find out about being here.

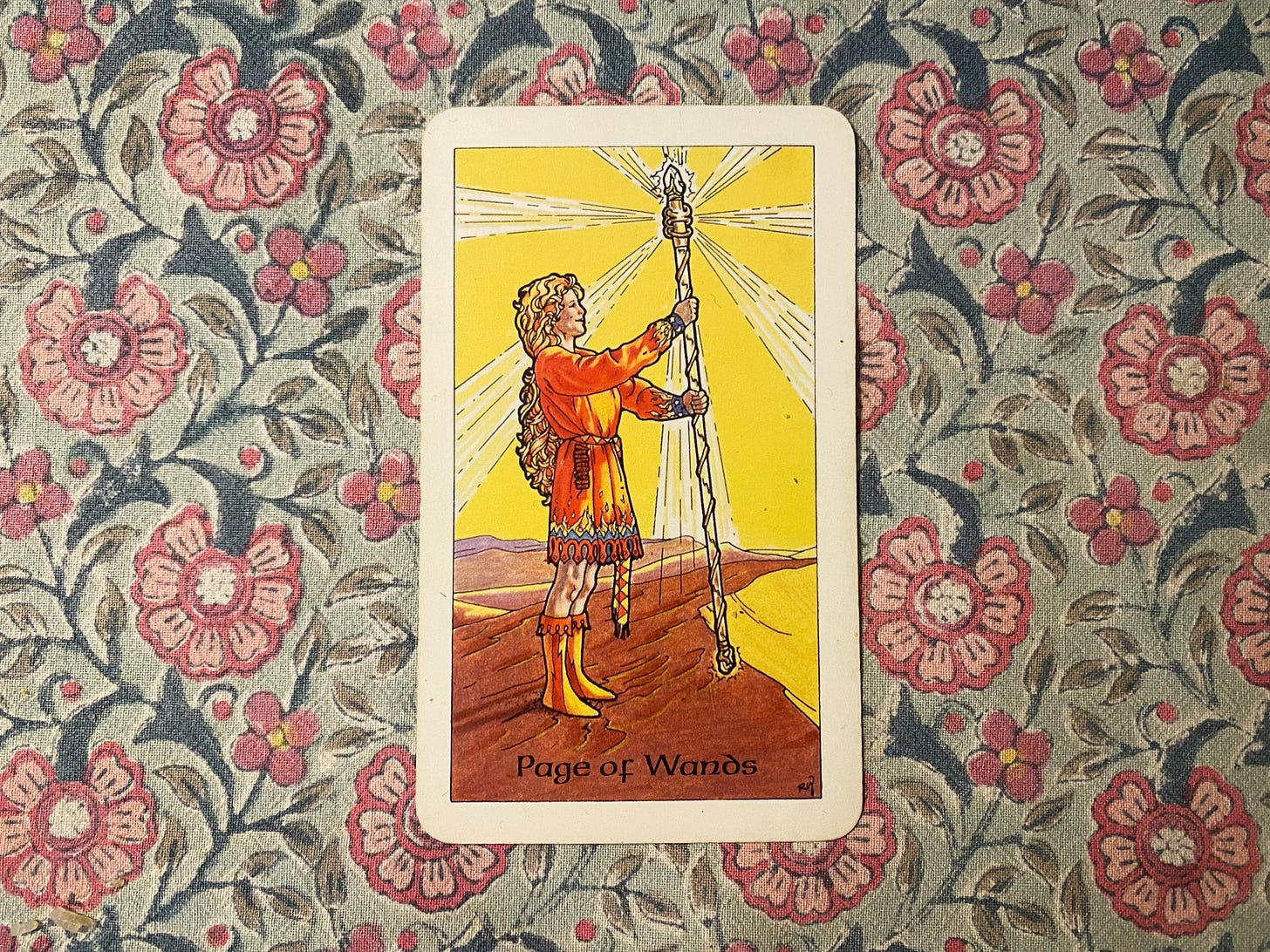

AZ: Shall we move to this card, the Three of Wands?

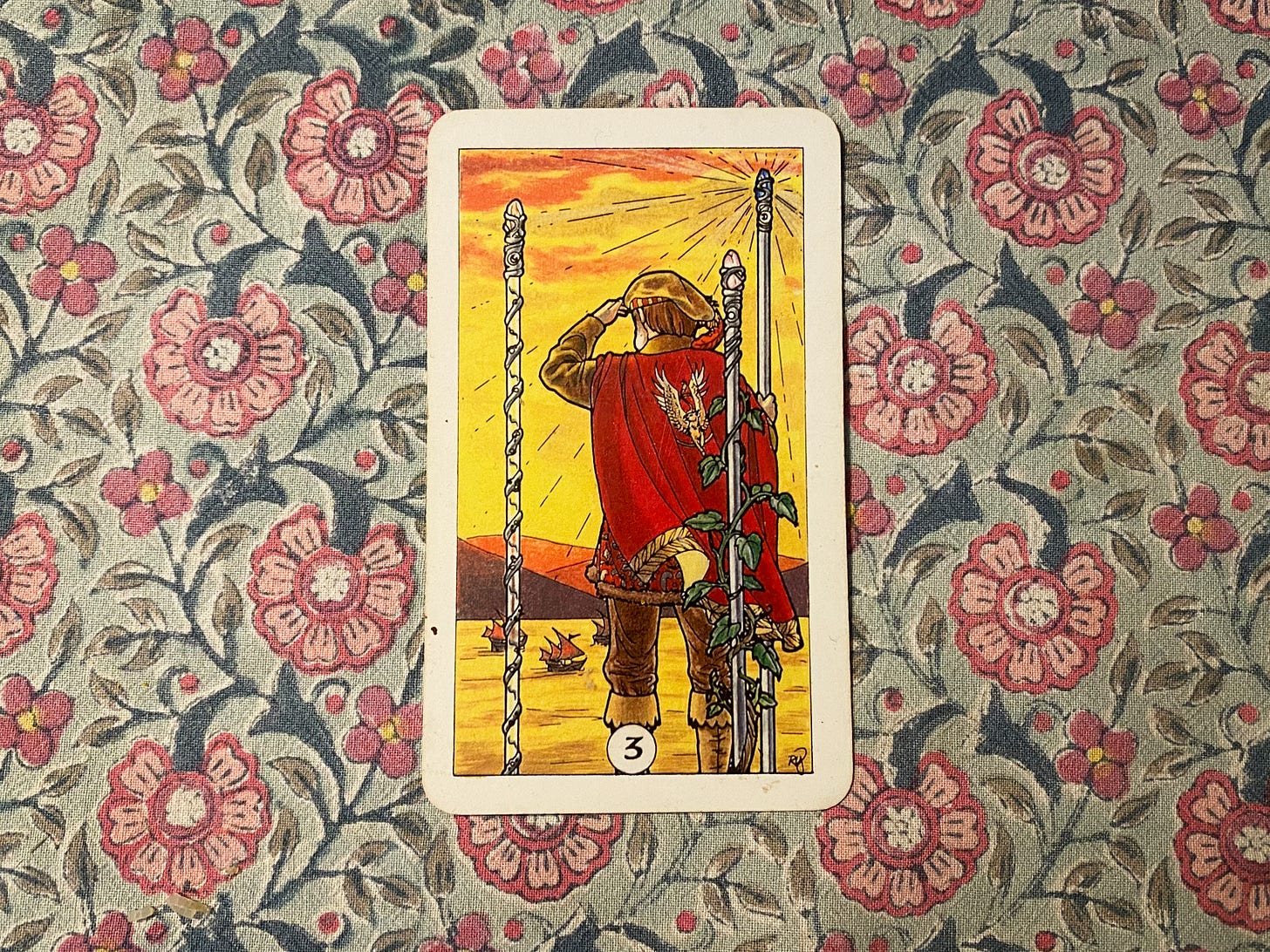

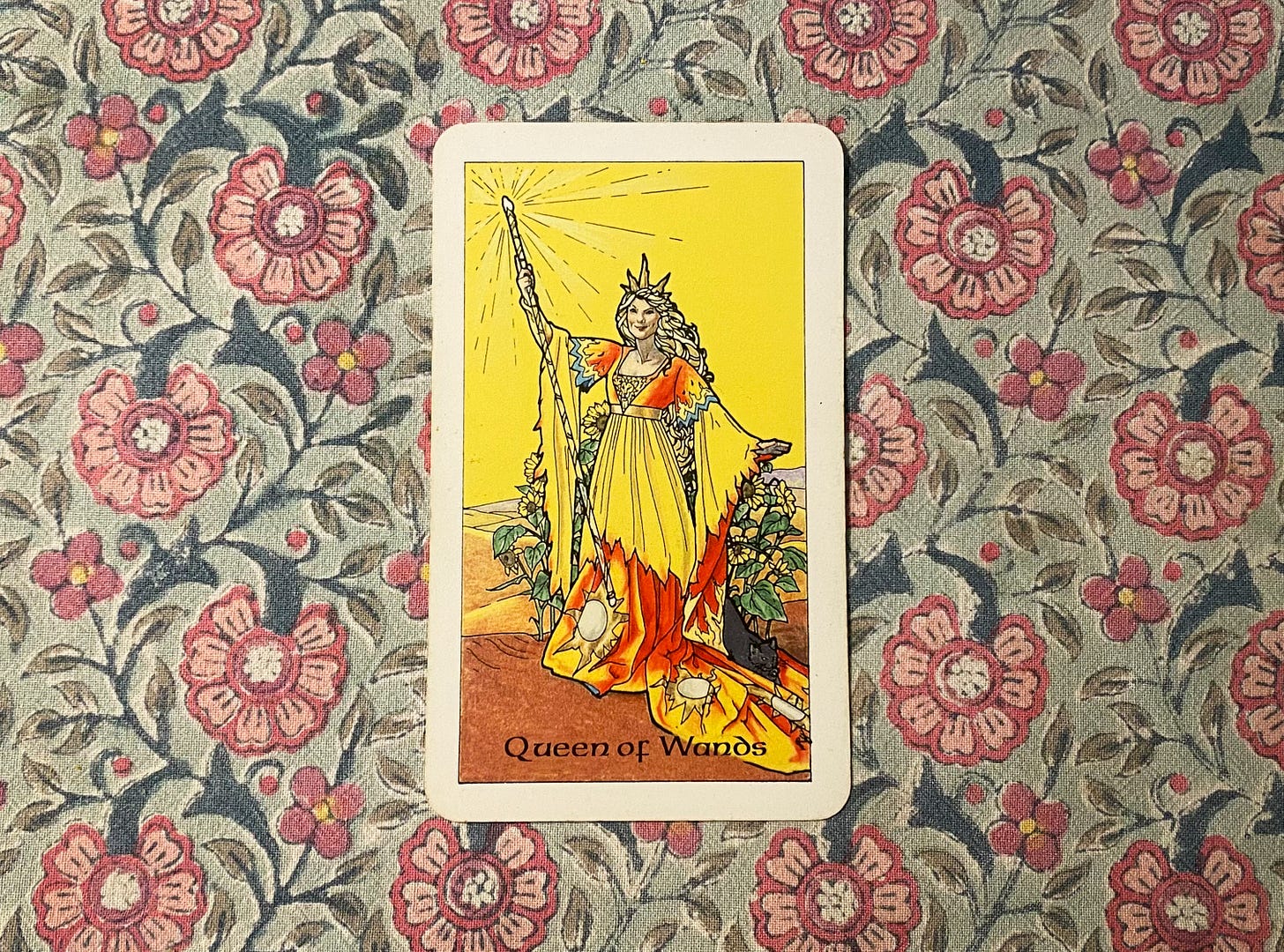

SD: I think it’s about my creative practice. The Page of Wands is the beginning, and I’m changing; and the Three of Wands is me landing in this whole world of practice, and of my projects. The Queen feels like it’s about the Creative Body Process, and me embodying myself as a woman.

AZ: Yes. “This is a good time to publicise your creative accomplishments. You may find yourself shipping your goods and products to a distant location.”

SD: Yes, that’s all about my practice. These cards tell a story about my creative life: the Page is the birth; the Three is me working, and my work moving all round the world; and the Queen is me actually standing in my garden. It’s the manifestation.

AZ: I’m wondering how you relate to the idea of success, and being rewarded by institutions. You’ve had a lot of it over a very short time. How do you feel about that?

SD: Well I began from an unusual place, I think. I still don’t feel like a photographer, it was just part of my evolution. It was something I had to do. I wasn’t looking outside of me at the time, when I started taking pictures. Looking for Alice really was my first piece of work. Everything was driven by how I was feeling, and I was trying to embody what was happening for me: to resolve it, to understand it, to lay it down. That’s kind of the premise of my practice. I wasn’t thinking about awards and validation. The validation has to come from yourself, otherwise it’s empty, and it disappears very quickly.

At the same time, I was entering things, and they were useful. I think ambition is fine if it’s managed well, and doesn’t obscure creativity. I wanted to exist within this new world.

AZ: This is what it feels like this card is: it’s looking out to the new land, the distance to travel.

SD: It was exciting. I was travelling with my work, I was meeting very interesting people, I was meeting creatives all the time. Many of my friends, now, are in the world of creativity. There’s nothing I like better than sharing that; many of my ideas do come from those conversations. I immersed myself very quickly in it, and in many ways, I took refuge within it. I felt like I’d found a home. I felt I had landed. I think many artists do operate as outsiders; you see that within their families, when you speak to them; the middle child, the disruptor. And it’s through art that we make sense of the world.

I think that really, very clearly, this card references so much about that period of time. And I do see it as a past, actually, now; an extraordinary period of time, and much valued friendships. It always comes down to friendship, and community, and relating, and connecting.

AZ: How do you see your work as a psychotherapist in connection with all of these things?

SD: I did this absolutely extraordinary Buddhist Western psychotherapy training, and that training was the container for the work that I’m doing. It liberated me.

I think ultimately being in that role, in that capacity, what you hear is all about human condition, and non-separateness. You see the lengths that we have to go to not to reveal who we are, due to shame, and what we inherit from family. I know how hard it is for people to make that transition back to self, and love, and connection. This is why we choose to go to psychotherapy, ultimately: to come back home.

AZ: It also feels like it was this long priming of the canvas for all of the work that you’re doing now: the space that you hold in your photography. It feels like so much of your work, and your gift, is about holding space in a particular way.

SD: It’s holding space, but my container is vast. Having very volatile parents, in and out of homeless accommodation until I was 14… I’ve sat down right at the bottom, and I have looked up from the bottom, and have begun to find a way to be here, to bring my spirit here, and not out of my body. Hence all my twenties, taking recreational drugs; I was out of my body, playing. What was so good about that period of time was the dancing. It brought me to connection. But I had to ground myself — I had to bring myself home. So I’ve been leading myself by my hand through different trainings, and different experiences, and different relationships. The psychotherapy was just one part of that, but it was a significant part. The early part was the raw stuff — the material, the richness — and psychotherapy was the integration.

AZ: And then we get to the Page of Wands, the bolt of inspiration, before the setting out — the Three of Wands — and being on the journey.

SD: And inspiration. I mean, all these cards are about inspiration.

AZ: Of course. They’re all about drive, and libido —

SD: And passion and vitality. Everything I’ve done, I’ve made the decision from passion.

AZ: I’m interested in what you mentioned earlier about being led by faith.

SD: My psychotherapy training was Buddhist psychotherapy, but my deeper faith is in God, and I don’t really share that. It’s quite nice Nick Cave’s normalising it — talking about it shamelessly, how it informs his work. He has a critical view of it, as I do too. My faith is very quiet, and doesn’t really need to be shared with anyone. But it’s what’s flows through me and my work. I can see my faith in my work. Faith, to me, is just love. And so I feel huge reverence, because I feel very well. I really trust my mental health. And I really trust that the work is coming not through ego.

The work that I’m making currently with my son Luke, in the garden, comes from our faith. We both fully respect that the work has been given to us. My understanding of creativity is that there are narratives and themes and stories that anybody can receive, at any point, about that particular time. So the work that we’re making in the garden is a narrative of the time that we’re in, and we were open to receiving it. It came to us; it doesn’t belong to us. Our ego might want to believe it belongs to us, but we were just given the paintbrush.

The work in the garden was another one of those moments of inspiration — a transmission. “Why don’t we make the garden into a place so beautiful that people want to be photographed by you?” This was Luke’s prayer, and an offering to a mother who was sitting at the kitchen table so profoundly distressed by a traumatic event, which I can’t share, that went on for two years. And that moment of light that he blasted into my world — it was like a resounding yes.

The vision was to clear our completely abandoned back garden. The back garden was me; the back garden was us; the back garden was humanity. It was abandoned, and then we chose to lift the shadow. When we lifted the shadow, what we had was love. What we had was nature being the teacher, being the wisdom, calling in people, calling in lovers, and the disenfranchised, and the broken, and the connected, and people needing respite. It spoke to all of us.

It was this extraordinary metaphor for the human condition, and a metaphor for the human heart. Every single project has a natural cycle, and every single project is a teacher; so as I’m drawing to the end of it, the integration is coming, and I’m feeling the ground. I’m ready to offer up my gratitude for the work that I’ve been given, and for me and Luke to have come together in the work, and I’m ready to move on.

And the moving on has been extraordinary, because something’s coming up behind it: the Creative Body Process. That began about 2 years ago, but it’s only in the last 6 months that it’s really waking up.

AZ: I was just thinking about how on the Page of Wands there are no plants, then on the Three of Wands there are these shoots beginning to grow, and then on the Queen of Wands they’ve burst into these sunflowers that are all growing around her, and sunflowers even on her robes. It’s like there’s been this transformation for you, and all this very literal growing of flowers — and now here you are in this garden that people walk into and cry.

Shall we move to the Queen?

AZ: It feels like this is you holding the process.

SD: I never imagined there’d be another evolution for me. Yesterday I was thinking “I wonder if I’ll take pictures anymore”. And with that came a certain quality of grief, and also grasping. But remember when I started my photography I had to give up psychotherapy because I didn’t want to dilute my practice, I had to deeply commit. There’s a quality about that with the Creative Body Process. I look forward to every single group that I run. I’ve embodied the whole process, and so something might have to give. But it doesn’t matter, that’s the point. We imagine it matters, our ego says it matters, but it doesn’t.

The Creative Body Process came about because I believed that people needed a place to be with their creative practice. They needed to get behind the scenes, and be heard.

AZ: I know it’s important that the details of the process are withheld, but can you talk about it in more general terms?

SD: A couple of years ago I was asked to deliver a workshop, and I thought well, if I just go in and say “this is how you take a portrait”, it’s the way I would take a portrait. You can never get away from your own authorship. I thought actually, I don’t want to take away anyone’s agency, so let’s find out what else is going on that they’re obscuring, or that they can’t acknowledge. Let’s use the group to enable them to see what they can’t see. I wanted a group where they’re all invested in each other.

I walked into the space, and I said, “this is what we’re going to do”. It certainly wasn’t considered; it happened as I was approaching the room. What happened was extraordinary, and it’s the same with every single group I've run since. There’s something about not having to make work. The artists don’t have to perform, or come with an edit, or with a camera, or whatever medium they’re using. What I noticed instead was a coherent sense of responsibility towards each other’s creativity.

The Creative Body Process is premised on the idea that we, in the West particularly, are all meeting the world from our minds, and that we are struggling to access the intuitive body. So, to make that journey from the mind to the intuitive body we need unravelling. Within the process of the group, we fast track it. It’s a bit bumpy, but we get there, and when we get there, it’s liberating.

AZ: A fast track into the heart.

SD: Yes — a fast track into the creative body, into the intuitive body. The more we are in our intuitive bodies, the more we will hear what work we need to make, and how we need to make it. That’s the premise of the course. It’s a therapeutic course, but actually it’s about creativity, because my belief is that creatives need help, and they need all the help they can get — because when we’re not being creative, we don’t feel well. Creativity is the path to wellness. It’s our libido, it’s our vitality, it’s all of it. It’s where we hold our passion. We have to put our creativity on an altar, and we have to give it space, and we have to be reverential towards it, and be holy about it, because the creativity is us. We have to kind of turn the mirror onto ourselves, and say “here I am.” Put the brakes on the outside world, and all the “I must, I should, I could”; to quieten everything down, and listen to our inner narratives.

The union is with yourself. The relationship is with yourself. And that’s where all our practice should come from, not what one believes other people expect of you, or what you think is responding to the current narrative you see around you. That’s the liberation in the work. I feel so well whilst in the workshop, I feel so well afterwards. The workshops have a constant waiting list, and people don’t even know why they’re coming, but when they arrive, they go, “actually, that’s why I’m here”.

It’s a strong process, but because it’s strong, what you have is this extraordinary sense of solidarity in the group. What we don’t experience in the art world is much solidarity. I know that, because I see the vulnerability and the anxiety and need for approval; but when you get a group of creatives together who are only thinking that they want that person to do well, it’s an extraordinary thing to witness.

They’re reigniting their practice. The groups are really tight with each other still, for months after, because they’ve been through the process. They’re often exhausted on the course, but when we’re tired there’s less resistance, so that really works — because what we’re dealing with is resistance to change, resistance to meet ourselves, resistance to understand what we need to say about being here. We go through this process, we take them into the night, owls are called down to them, there’s time for self-reflection, and then I work with these exceptional writers that ground what’s happened.

The quality in the group is that there’s just one heart. There’s no splitting, there’s no separation, there’s no looking over each other’s shoulders, it’s a democratic space. There’s no judgment. It’s a rebirthing of purpose — an absence of purpose drives us into despair. By the time the workshop finishes, everybody’s found their beans again. They’ve got their chemistry back. When you see the aliveness, that means that we can fully access our creative narratives.

AZ: And that’s the Queen of Wands.

SD: And that’s the Queen of Wands. Her heart’s open, she’s embodied, she feels really well. She’s found her purpose. I think we can all access that. When you see that happen within the group, it’s an absolute joy.

Every month I’ll be asking each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue.

Siân Davey’s recommended reading:

The Passion — Jeanette Winterson

Paradise Lost — John Milton

A huge thanks to Siân Davey, and to you for reading. You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below:

That was lovely!

Lovely. So enjoyed this. Thank you. And using the tarot as a guiding thread, perfect.