A Conversation with Lúa Ribeira

"...all the possible tenderness, all the pain, all the masks and whatever is behind them."

Subida al Cielo, Lúa Ribeira’s remarkable first monograph, collects work from five different series. Made across four countries from 2016 onwards, these bodies of work often depict people on the margins: those experiencing homelessness in Bristol, for example, or the group of young men planning their crossing from North Africa to Spain. In the book, though, the works are not contextualised by titles, captions, or description. The series flow into one another, sharing a common directness and simplicity: people framed starkly by sky or grass or water, their bodies often in motion or otherwise contorted.

Years ago, when I first came across Ribeira’s work, I remember finding it troubling and feeling I couldn’t make sense of it. I didn’t know what I was meant to be seeing or thinking. I began to look closer at the unease I felt, my reaction to what I perceived as confrontation. Why did I expect to be informed and reassured by looking at pictures? It felt as though the work was revealing something about me: the separations and categories that exist in my own mind, my craving for certainty and tidy narrative. I feel now that this is exactly the point — her work is confronting precisely because it doesn’t dictate a particular reading. Her subjects retain their essence.

The images in Subida al Cielo are full of energy and tension. They challenge rather than soothe. By stripping away the gloss and narrative shaping that we’ve come to expect photographs to provide, Ribeira is reaching for something more elemental, even archetypal. Her gestural photographs — produced during intense collaboration with her subjects, with whom she forms close relationships — begin to seem like symbols, as potent as they are overtly simple.

In her own words:

"I am interested in nuns, thieves, and gardens. In the rotting body, witchcraft, hotel receptions, and heaven’s gates. Phantoms, funeral directors, and gravity.”

This short artist statement works just as Ribeira’s images do. It makes no claims about intention or effect. Like the photographs, the list of nouns is stark and direct, yet it’s in the friction between them — the different directions they pull in, the imaginative effort that we have to make to move from nuns to thieves, and so on — that the work is found. All of the tensions the list provokes pull on each reader in different and unpredictable ways, and this ambiguity is at the heart of Ribeira’s project. She doesn’t hold the viewer’s hand or assert her own view, instead letting the work happen in each of us.

Alice Zoo: I thought it might be interesting to start by talking about Arbus, who is especially on my mind at the moment, and who we were messaging about briefly earlier this week. What were some of your earliest encounters with her work, and do you remember your reaction to it? Have your feelings about her work changed throughout your own development as an artist? I'm thinking about Aristócratas, of course, but also the way that you seem to be a natural inheritor of hers in general, in your interest in the elemental and the mythic.

Lúa Ribeira: I remember feeling that her work was asking, in a very open-ended way, uncomfortable questions, and it was stimulating and challenging, like a source for me to reflect. Also the way she understood the work — it was beyond the medium of photography, and more connected to a philosophical search. I felt connected to that search and admired her responsibility towards a certain honesty that I think is not easy to devote yourself to.

My feelings have not changed: to look at her work is always inspiring and overwhelming, as if the images have all the possible tenderness, all the pain, all the masks and whatever is behind them.

I work very instinctively, and when I was studying I shot a lot in order to see what I was doing. Then it was a matter of deciphering what was happening during that less conscious process, and I think it was, and still is, something about encountering people and making images together, united by something. I was also drawn towards images related to the mythical, the archetypal, something that may transcend the anecdotal and temporal, which had something rooted about us… and Arbus was a master of this.

AZ: Yes — and it feels as though you’re also similar in the way that you value the encounter itself, and its intensity, so highly. The images almost seem as though they transcribe that intensity more directly than the people and landscapes themselves — as with the feeling of adrenaline that was the thematic centre of Los Afortunados.

I know you often spend a long time with people, in their environments, before you find a way to begin photographing together — you only began making photographs for Aristócratas during the third summer you spent time there, for example. I’m wondering if there have been times when your encounters with potential subjects haven’t led to photographs — when a way to photograph never became clear? Or when the photographs didn’t reflect the encounter in the way you had hoped? What happens when a certain intensity is unrealised or untranslatable? Do photographs — or even whole projects — ever get abandoned, or fail?

LR: I think, up to a point, it is always untranslatable and unclear. There is a big gap between my experiences working and the final image the viewer sees, which holds so much ambiguity. I am very resistant to sharing testimonies or information because I always find one question behind another, so at the end it is more about the images and what they can do to us.

Often there is that long period before the images happen, and that long term encounter is what informs the work. For instance Aristocrats takes place in the context of an institution that takes care of neurodivergent women, or Los Afortunados, on the Spanish-Moroccan border. The possibility of sharing time and space outside the productivity or charity systems that could have lead me to work or be in those places is very important for me. It’s more intimate: it’s about togetherness as a form of transgression; and clashing with structural separations, the barriers between us; and seeing how strong and fragile those separations really are.

In terms of expectations, I know that the encounter will be the accident that provokes the images, and I am looking for images I can't imagine yet, so I am very aware that whatever preconceived visual is in my mind won’t be as interesting as the image resulting from the real experience.

I am not very insistent. When there isn’t the right feeling I quickly move on. And yes, the work is full of failed attempts, of fear, shyness and walks that take me nowhere. I often exhaust myself but later on also comes a moment of acceptance and hopefully a bit of lucidity. I have abandoned past project ideas that were too formulated — they were already resolved, and didn't lead to exploring something beyond what I already knew.

AZ: It takes a great deal of nerve to work with such a high level of ambiguity, and push hard beyond the known and understood. I often feel that one of the reasons that images are so hard to control is because they're beyond language — they have an inherent volatility. That’s something I struggle with and struggle against, and so I really admire the way that you work with this volatility, using it as a source of power.

Speaking of the unknown — ideas of transcendence and religiosity are very present in your work, as well as in the way you talk about your own philosophy and working methods. I’m wondering whether you see and experience these things — like magic, witchcraft, and the divine — as real forces in the world, beyond their interest as ideas to explore in your practice? Why are you drawn to them?

LR: For me that volatility, and even futility, can be hard but also a relief at the same time. A gap that allows the search to continue.

We have a tradition of Catholic art in Spain, both painting and sculpture, which appears ubiquitously in religious celebration, folklore, architecture, etc. We also have the Baroque, with all the gestures and representation of experiences connected to pain or suffering, and the dramatism of it all. I think it does something to us — when we stare at certain images for a long time in a church, for instance. It’s almost like a way to train ourselves to deal with the unknown, the idea of death and what that may mean. Something that is transcendental, important. I guess to answer you, my interest in those questions is what defines my practice.

I am not sure I’ve experienced magic in terms of witchcraft or the divine in a straightforward way, but I think I am open to other people’s experiences of life, and somehow I don’t have the need to define where a certain idea of reality ends and fantasy — or another idea of reality — begins. It is often the ones perceived as mad who express the most lucid thoughts, isn’t it?

AZ: I feel as though there’s a certain amount of the numinous in the gap itself: the search for an image or the right set of symbols. How is it that a project doesn’t seem to be working, and then suddenly it does? It feels like there’s magic in that, or at least a force that we don’t fully understand, but can absolutely feel and experience whilst making work. Another reason that I find photography so challenging is because the surface of things feels like such an impossible point of access for all the mysterious interior forces that interest me, and yet surfaces are the material that photographs work with. It feels like trying to produce a dream to be interpreted.

What you said about training ourselves reminds me of something I’ve heard you say about your practice of gathering reference images. Subida al Cielo is unusual and generous in the way it includes a glimpse of your process: your drawings, paintings you’ve been looking at, film stills, and so on; I read that you think of collecting these images as a “ritual of preparation” for your work. Can you tell me some more about that? And can you imagine making works entirely in another medium one day, as part of your practice — painting, drawing, sculpture, performance?

LR: You are right, there’s something that clicks and we’re never quite sure why. Also, related to what you’re saying, I really like something John Berger wrote about Spanish art and how it was often designated as realist because the surfaces are rendered with great intensity and directness, but with the awareness that there’s no point in trying to see through appearances: “Let the visible be visible without illusion. The truth is elsewhere.”

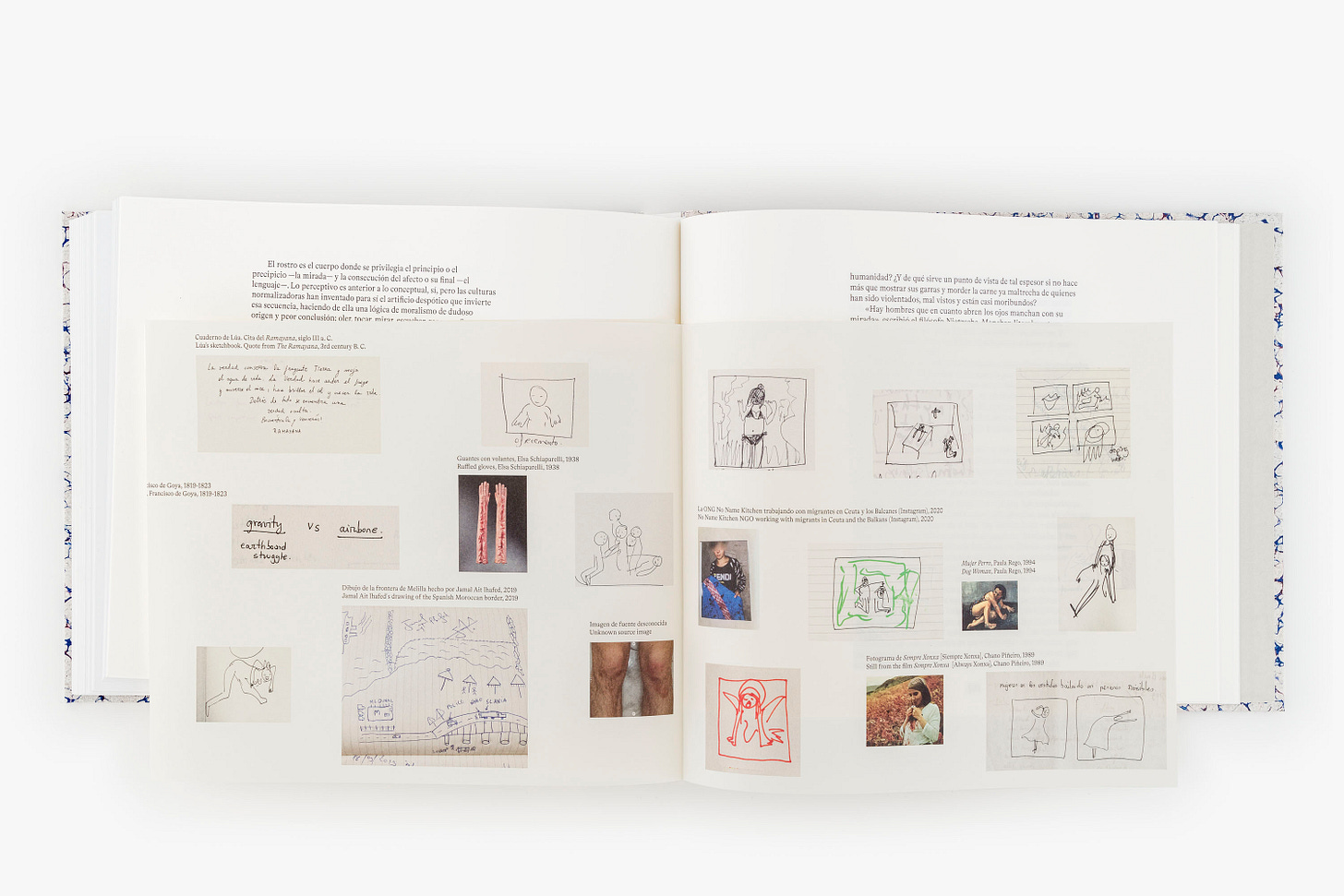

Subida al Cielo contains five different series that merge into one within the book and define a way of working I have been developing. Whilst working with the publisher, we were thinking about how to include the reference images I use: from painting, vernacular, film stills, as well as sketches and text fragments. They all work together in relation to the questions I am facing in each series. It has been very interesting to see how people engage with this part of the book, and we’re considering making a companion that expands on it.

I would say it’s a ritual because it’s not too useful technically. I’m not preparing the images; it’s like a false attempt. I work too accidentally, and with what happens in the moment of photographing, so all these previous ideas are ready to be broken from the start. But still, there’s something very important in them, like a starting point of confidence; the notion that something is possible, and a way to train oneself, perhaps subconsciously.

I see that some of the sketches have the same energy as the photographs, and I have done sculpture before as a separate thing, but I like the idea of devoting myself to photography, not to give up on the medium whilst I drink from literature, painting, cinema and of course daily life.

AZ: Oh, that Berger quote is great. I went back to read the essay it comes from, and this line also made me think of your work: “The Spanish painters, with all their mastery, set out to show that the visible is an illusion, only useful as a reminder of the terror and hope within the invisible.” It makes me think of Arbus, too, actually.

I’ve been wondering — do you feel part of a tradition of Spanish art? To what extent does your creative identity feel connected to your nationality? And beyond that, does your work feel connected to your identity in general, or does it feel separate, like its own entity with its own character?

LR: I am not sure if I feel part of a tradition like that. It’s complicated, relating the medium of photography to fine art. I feel inspired by some of the Baroque literature and art. I’m obsessed with Goya, but I guess everybody is. Italian Baroque is also fascinating, and so are other movements and artists that came later. I feel I have my “maestros” that I can always go and look at, and they all relate to each other somehow — even though they come from different times and movements.

The nationality question is tricky because I am Galician; we have a different language and heritage. The fascist dictatorship in Spain ended in 1975, and Galicia was one of the territories which suffered a harsh repression in relation to our own culture, and this is still very problematic. The consequences are also palpable in my generation, and I know the themes I have been mostly dealing with in photography come from an identification with, or certain sensibility borne from, those systems of oppression and what they cause. I often say the work comes from a political motivation and it’s only later on that it turns into something more fragile, more connected to deeper questions and uncertainties. But yes, the work is totally connected to the place I come from.

All images (C) Lúa Ribeira, from Subida al Cielo, published by DALPINE, 2023.

Every month I ask each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue.

Lúa Ribeira’s recommended reading:

Sweet Nothings — Marlene Dumas

The Ballad of the Sad Cafe — Carson McCullers

The Thief’s Journal — Jean Genet

A huge thanks to Lúa Ribeira, and to you for reading. You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below:

Really interesting interview. It was a great inspiration to read it!

Great interview guys. 🙏🏼❤️💯