A Conversation with Katrin Koenning

"...the tear, the hope, the bird, the human. The stone, the tree and the dream."

I first wrote to Katrin Koenning in 2018, when we had a conversation like this one for Splash & Grab. I felt that this kind of format — writing back-and-forth to one another, slowly — was so interesting and worthwhile: a chance to gather thoughts and allow them to build and accumulate, and to move in unexpected directions. It was an exchange that I thought about often in the years that followed, and had always wanted to repeat. I’m so happy that Katrin agreed to revisit it, even in the untested and still-experimental waters of this newsletter. Thank you, Katrin!

This time, we spoke about Midnight in Prahran, a long-term work Koenning has been making about her local community since she moved to Melbourne in 2009. The title comes from the walks she would take during periods of insomnia, coming to know her neighbourhood on foot, at night. As time passed she began to know her neighbours better, until they became part of the work, too; the work shifted, becoming a story about the practice of returning, belonging, and relating to one another.

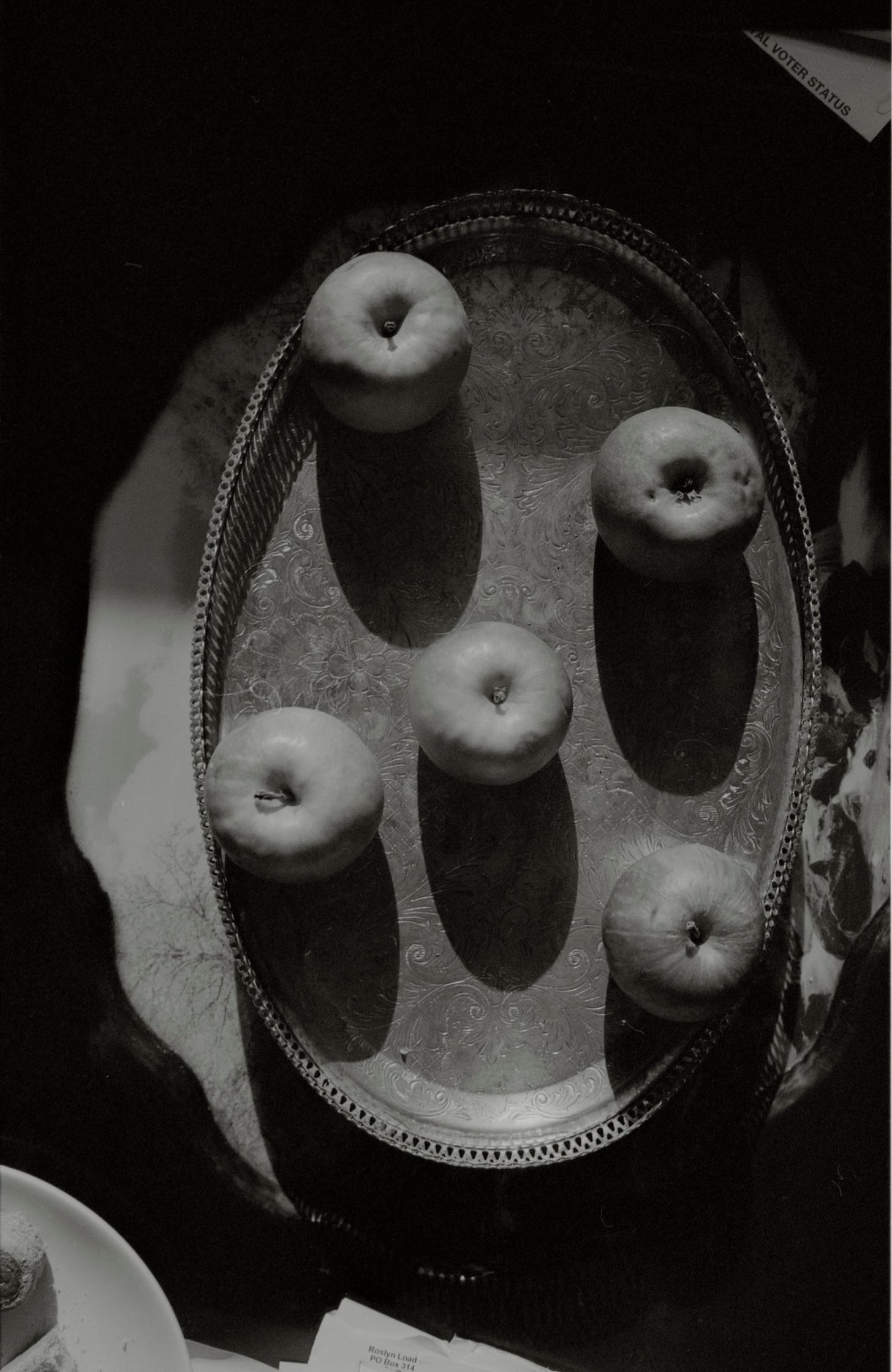

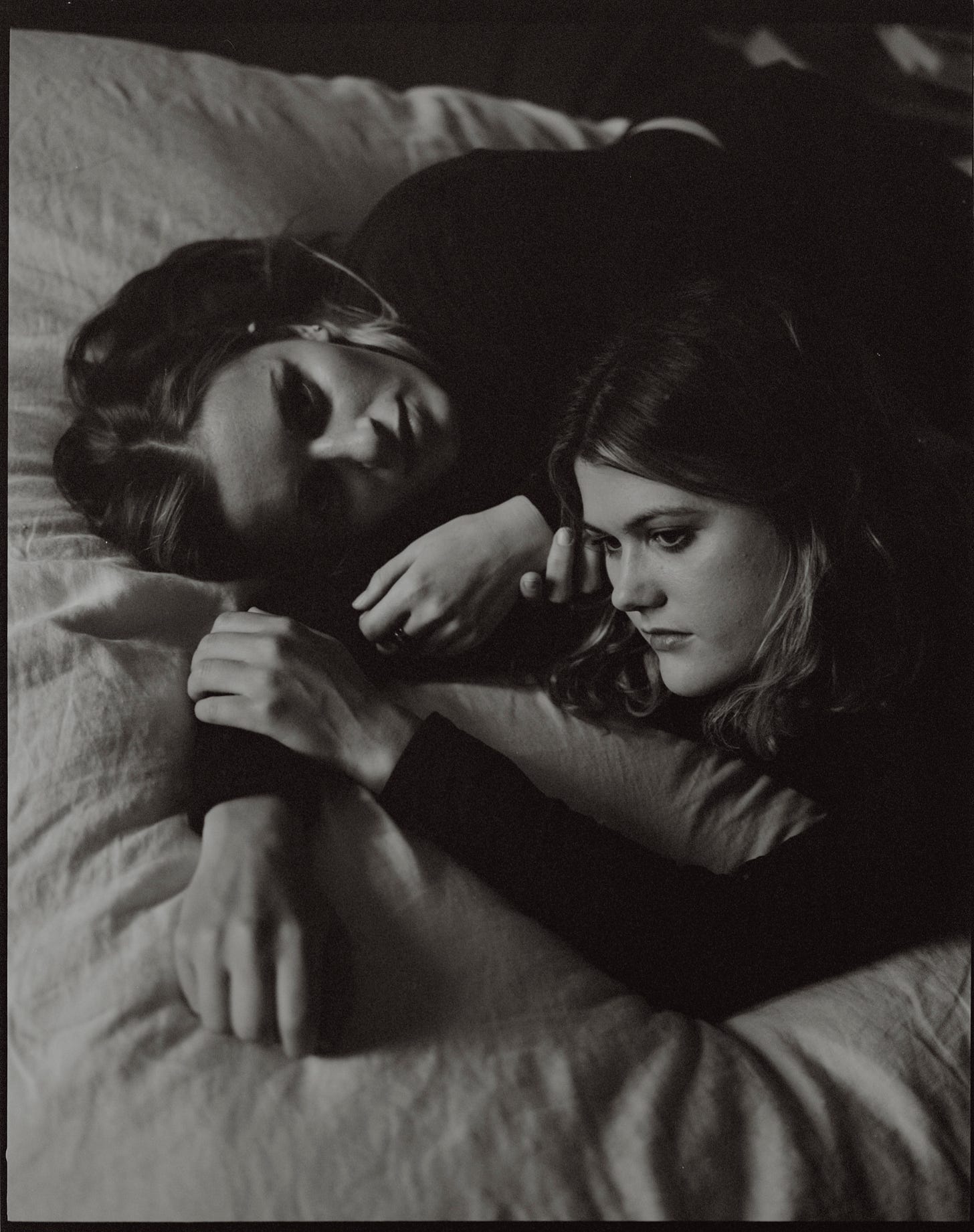

Koenning’s vision of Prahran is mysterious and fragmentary, rendered almost entirely in a monochrome that is at times deep and velvet, and at others bright with flash. It seems to have its own upended logic: animals are stilled and birds grounded, while people are often tangled together, or in jostling motion, or upside down. She depicts her neighbours as frequently as the smallest and most transitory details — everything deserves to be seen, as she told me years ago. Through these images we develop a sense, not of a fixed truth of this place, but rather of a series of emotional textures that these pictures allow us to brush against. The feeling is casual and intimate, strange and tender.

As we wrote to one another, I kept thinking about Koenning’s obvious joy in relating to her home and her community in this way, the gratitude and optimism she brings to her everyday encounters. She writes of gifts and privileges, presence and community and love; the portrait as an act of service, the reflection of a moment of drawing closer. I’ve come to think of her photographic practice as a devotional one.

MIDNIGHT IN PRAHRAN

It’s always six, Andrew says towards the end. The hallway wears an old-school clock, one that is stuck forever. I have to think of his son’s mother, how she’d lost her life. Alan dresses like it’s Sunday – vest and hat and all. He too speaks of the absence of a mother while we wait for birds. He tells me come along to dance class (over 65’s). There Aubray moves like he is twenty, swinging two mad legs. I think of love and injury, how things are found and lost and found. Dancing defies the ghosts, they say, and time is time.

In winter, once the leaves have fallen, morning fogs come settling in. They bring with them a swallowing effect – the urban world, not mute but muffled and a bit drowned out. The chilly air then smells like fire, coffee and damp earth. When the local magpie sings on such a morning, over on the window tree, her call is loud and wallowing. You’ve heard? It comes in such assortment that your head explodes, seducing with a thousand faces.

Drawing on a variety of media to find, collect and visualise stories from the suburb of Prahran, South of the Yarra river, Midnight in Prahran is a localised work about fabrics of a particular community. It is imaginary of a community in fluidity; a little like a never-ending puzzle or a humming swarm that is in constant motion, never static. Within this humming swarm, every thing wants to belong — the tear, the hope, the bird, the human. The stone, the tree and the dream.

Alice Zoo: I wanted to start by talking about time. It’s been four years since we last wrote to one another, which seems an almost impossible distance given what’s happened in the interim. I feel changed by these few years, and when I was planning this conversation I re-read my past messages to you as though they were written by someone with whom I’ve since lost touch.

On that basis, it’s especially interesting to be considering a work for which time is so conceptually essential; both on the large scale, in the swelling force of years — you began making the project thirteen years ago — and the small, in the fineness of minutes as they’re lived. In the accompanying text you describe the hallway clock stuck forever at six, and yet it’s midnight in Prahran.

“Time is time”, you write, which feels like an appropriately koan-like way to frame something that seems to have so many different qualities and bearings, that acts on us all so differently. Could you tell me about the way that time has acted on this work since 2009, and how you’ve felt about it as these years have passed? Have your feelings about time — if we could think of it as a kind of substance, a matter of the work — changed, either personally or with reference to these specific images and this specific story?

Katrin Koenning: It’s true, I relate to this so much; words from four years ago feel distant, a little like the language of a shadow-self. Since we last spoke, everything has changed — inside and out.

My feelings about time, personally as well as in practice, have changed so much since 2009. In fact thirteen years ago, to me, seems like something from another era. It’s so curious to think back and know, in present, of all the things that have occurred in the self and in the world since then, and to think that one had no idea of all that was coming (and going).

I began the Prahran work when my partner and I moved down to Naarm from up north in 2009. It felt natural; from when photography crashed into my life I have loved working with my backyard, in my immediate communities and with stories that are close.

It was also a way for me to feel myself into this city that was so new to me; a way to make myself belong. Over time, the work has meandered through different iterations of itself. In the early years large parts of it were a kind of walk-photography: the suburb as mini-ecology, and walking as a giver of language. There were also photographs around the home, and with people who would stay and live with us. Since then, both of those have moved to become their own ‘projects’ (I always feel stranded in that word). I began working much more closely with community in 2017. By then, my ‘being in’ had changed. I knew the place and felt part of its fabric.

What an enormous privilege, to witness things through time. Never the same, always different, always themselves. A thousand varied states to everything! Like most of my work, Prahran sees me return to something over and over, through the years and through the seasons. The same clothesline, a pair of rocks in conversation, a neighbour-cat, the same tree perched between two houses and so forth. There’s a frenzy to the process; it possesses me.

It’s so curious — during or since pandemic time, time fell away from us; cast off. Every moment was intensely past present future, and yet totally suspended all at once. It sat like a thick fog over everything, and yet it was getting away. I feel more intimately entangled with it I think, closer to it. There is a renewed certainty that every minute moment counts; that every second matters.

AZ: It makes sense that such a long-term work began in walking: a measured, necessarily patient way of moving through a place, and a way of relating to places and people that is, obviously, embodied. It makes me think of what you’ve said in the past about slow looking. There’s time to consider every small thing: laundry hanging out to dry, a discarded piece of fruit, the way the light moves differently through the year. It’s very striking, too, to consider what you describe about frenzy and possession: that these intensities of the mind might be channelled through, or tempered by, the rhythm of a body walking.

This feels particularly pertinent given the past two years, and the fact that for a period of a few months a walk was the only leisure that was possible outside the home. I think many people began to rely on it in a way they haven’t before, and to notice the attunement that it brings. As someone for whom the practice has been so longstanding, can you tell me more about what you have found or learned from its repetition — by returning to things on foot, year on year, and by photographing them again and again? And could you tell me more about the idea of walking as a giver of language?

KK: Yes, it’s true — I think many more people have, though by forced circumstance, found the walk. Here in Naarm we were locked away for the longest total period of any city globally; our lockdown lasted two years really, with short bursts of ‘freedom’. Everybody longed to be together in a bodied way, and while of course being together offline was an impossibility, the street (our 5km radius within which we could move) was where one could reclaim or keep the body in the world.

I lost and found so many things inside of me during that time on the street, walking. I walked an average of 60-90km each week, just in my little radius. We were so lucky; the absolute periphery of our 5km was the sea!

For as long as I can think, walking has been a great source of inspiration and sanity. So much of my language comes to me like this. Observational language (this might flow into photographs or little paintings), sure; here a small black cat and yonder a chunky cloud above, seen in the act of moving through the world in this small way, but more than that. Language arrives that sits completely outside of observation; often whole sentences appear. They could be about anything! A sudden poem, for example.

This, too, is then a frenzy — I have to stop often in the flow of the walk and the stream of the words, to write them down so I can keep them. It also happens when I swim, fly and while driving long-distance, alone. It happens when my mindbody is moving in a proper way through space, surrendered totally into the temporal suspension of this way of being-in. Yesterday I drove for seven hours and pulled over eight times to write things down.

On foot you are closer to Earth, and you can feel everything differently this way (yourself, the world, your thoughts, the body...). The footed return is a double-privilege I find; witnessing a thing through time and doing so via a journey always nearest to Earth. You also anticipate your arrival differently when walking, I think, and your reunion with the ‘object’ of return. Everything along the already-seen path guides you that way, and is never the same. When I return to something over and over by foot, every time I do so a great joy manifests in my chest. It is the opposite of an extinction of experience; it is a total connection.

It’s very physical, it’s a presencing. It has something to do with love.

AZ: That’s so beautiful. It puts me in mind of what you say in the text about “a community in fluidity…a humming swarm that is in constant motion”. I’m picturing you alongside your neighbours, measuring out time in your walks, apart from each other but moving together, from your houses and down to the sea; everyone, everything, wanting to belong. I loved what you wrote in your recent entry for This Long Century, that “presence is liquidity, a perpetual non-arrival”. I love how counterintuitive that first sounds in relation to the human, but the obvious sense it makes when thinking of the natural world: the cycles of growth and decay, blooming and withering, herds and hives and swarms and murmurations.

I’m very drawn to the idea of the community discussed in these terms — as a part of nature, everything and everyone interconnected and interdependent. Everything on an equal footing; everything mattering. Could you speak about the process of coming to feel that belonging within your community, and how you began bringing them into the work in 2017? And the portraits — which are so arresting and immediate, at the same time as having a really open, relaxed intimacy — could you tell me about how you approached them?

KK: Yes, it’s always seemed strange to me to think of community as a closed, too-particular or only-human thing. As someone who left a home behind in place for another, belonging is always so multi-directional for me. A sense of it here in Prahran (on these streets, among these trees) grew naturally with time, and with my ‘being-in’. Again, time as a gift; through time you walk and walk and meet and greet. You come to know — you begin waving to each other on the street, across the hedges and fences — “hello!” — “oh hello to you too, what a wonderful day!”

You start to share little stories, people come to know your face at the bakery or at the markets, you know what time of day a certain shadow meets a tall wall and every day you walk to meet with Wendy the ancient white cat, on your way to catch the flock of local birds screech in the big old tree on Chapel Street by sunfall. So grows the invisible, magnificent web of interconnectedness, so grows relationality, and so grows, too, your ‘localling’. In this sense, the way people began to populate the Prahran work grew so organically, often through friendships found and stories shared and meals cooked.

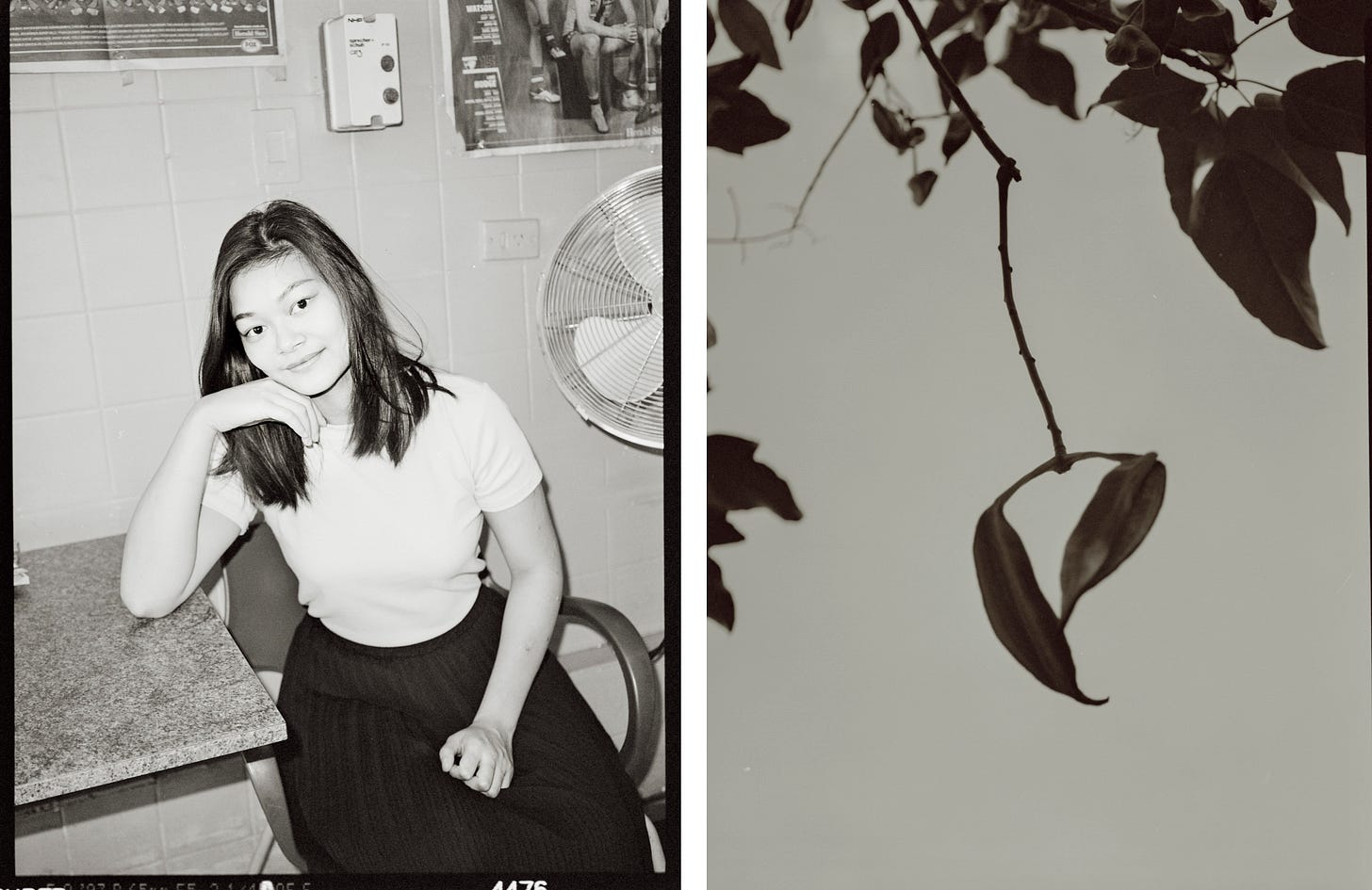

The portraits find me in different ways; one of my best friends used to live a street away from us with her little family; my dear friend Jackie lived next door (neighbouring is how we met); Andrew and Alan are members at the same pool; June and I met queueing at the markets; Emma helped me at Office Works where she worked when I needed to make little prints for an edit; Yassi works at Coles and we met out back on his ciggie break; Frank is my hairdresser; Joyce and Carmen work at the fish ‘n chip shop around the corner; and so forth.

Most recently I met Lucie at my favourite op shop — we were both trying on things and got chatting that way. Turns out she’s an actress and wants new pictures, so we’ll make a date of it when she returns from France. Sometimes as I walk with my camera I get approached and asked for a photo. Many people I meet by admiring their garden. A few years ago Alan invited me along to his weekly dance class for elders from the local social flats. It was love at first sight and until Covid crashed us all apart I went every week, every week. Mostly we danced, ate biscuits and told stories. Sometimes we made a picture. Dance class is how I met Lidia and Albina. Lidia is 70, you’d never know! She dances like a star and sews her own skirts.

I love making portraits. There isn’t a formula I follow for the process — oh, or if there is one at all, it is that for the most part they unfold so organically. The portrait is the extension of the meeting or the connection, just a small part of it. The shared space, the space you hold together during that time, is the main ‘event’. Again, it has everything to do with a being-present-together, a drawing closer, and a multitude of sharings during that presence. Sometimes I might suggest a spot near the sun, mostly I rarely ‘direct’ anything at all. I love working with what a person might want from and for their picture. The picture just arises from being together.

Since December 2021, I have been working with a small rural community six hours from Melbourne — it’s a deeply proximate process by which the photographs are only just such a tiny part of a much bigger thing. Often there, I make pictures for people; pictures someone wants and needs and asks me for for one or another reason. This might be to document a friend’s citizenship ceremony for them, or someone’s wedding, or someone’s birthday-party, or a portrait with their pregnant belly before birth, or to raise funds for the Network House, etc. I love this because it means the pictures are actually useful for people. I always think my job is to make a portrait in such a way so that the person in it feels beautiful about themselves, and so that they can love their picture.

AZ: Looking back over our conversations, now and in 2018, I’ve been thinking about how distinct your works are from one another; the ways that — for example — Midnight in Prahran is a world away from The Crossing, not only in its subject matter but also in its visual language. I wondered how you think about these differences, and the different visual language you adopt between one body of work and another; form, and voice, reflecting content. I was wondering, too, whether you think of each of your bodies of work as being their own distinct stories, or worlds, and how you see them relating to one another, as well as how you see them relating to the world itself. Do you feel connected to terms like ‘documentary’? Or do you feel that each work builds its own world, its own story, that in fact has only an oblique or translucent or indefinite connection to the world as it is?

KK: The story or the idea invariably comes first for me. A story isn’t just something I make or partake in; to me a story is alive, it lives in the world, and it always wants something. Maybe it wants many things. It might sound a little abstract but I like to think of it as listening to what the story wants. What must I do to do it justice, to hold it best, to work in such a way that it is nurtured? What language or languages need I apply, or find, to talk to this or that idea, and how is my positionality? If the story and I want to be hopeful, I need to find a language to hope. If we want to mourn, then melancholy needs to be my tool, to whichever degree — subtly or bold. If the story wants both, then I need to assemble my languages and call them in for conversation.

I cannot speak to dancing ladies, for example, in the same way as I may speak to my dad losing his partner of 23 years in 2020. His loss is a story of ritual grief. Making pictures together during this time demanded of me an immediate and completely open process, so it had to be the Polaroid. This way, the very act of the photograph could be useful; it was a way for us to navigate through darker time, a leaning against the shadow. It allowed us to weave into the tearing. The Polaroiding in itself became a ritual too. Often dad would have ideas for pictures he wanted. Every night the three of us — dad, my brother and I — would review the day’s collection, spread out on the kitchen counter. [By contrast,] the elderly dancing ladies from the local social flats are lively, quirky, spirited. I needed to reflect this in my language and chose brightness and a little flash.

As I always work on a number of different things at once (often five to seven ‘projects’), the works inform each other, flow in and out of one another. They embody shared sensibilities, they interconnect and intersect. Much like the way in which I love to make — relationally — they are relational. Next year I have an exhibition for which I’m bringing migrant pieces from four different bodies of work, all made since 2020, into a dialogical space with each other. The wall will shelter their fellowship.

Photography is languages! To apply myself to the same formula would feel like a betrayal of its etymological capacities, and of the stories I want to talk to. I love to use fragments and slippages to suggest narrative spaces, communities and lived experiences that are connected, fluid and multiplicit. My work is always in and with the world.

AZ: It’s apt that, as an artist whose work speaks about distance, connection, the spaces between things and people — whose work is relational — you have this sense of each work as being alive in the world, with its own needs and desires, and which you then hold close to you and nurture. The way you speak of “we”: you and the story, relating, together. It’s as though this aliveness is the first connection, and then becomes the quality by which you connect to whatever the work concerns: your family near and far, your neighbours.

I’m also thinking about what you say about language, and conversation, and dialogue, which are inherently relational too. Your images are one kind of language, but then your use of words seems as fluid and specific as your photographs: the nouns as verbs (presencing, localling, Polaroiding), the joyful exclamation marks, the enigmatic tildes. How do you think about writing in relation to your practice? Do you keep journals and notebooks? How do words and images speak differently for you?

KK: Language was my first love. I learned two others apart from German growing up and also sort of taught myself a fourth. The worlds that words can build were always my somewhere to disappear, or to arrive in, or to take solace or to belong together with others; a place of infinite reveal and radical intimacies. I used to be mad about journalling. Every other thought needed to be held to give my internal archive a physical home. That’s no longer my practice but I still write almost daily. Words also appear in my pictures often. Text with photography is very important to me; I think they occupy different places but are of course inherently linked, like close neighbours. Pictures can be so good at feeling. They can get you right there in your centre with nothing else needed. It’s also beautiful that in their felt spaces, they can do things we lack words for or we can’t quite explain. I like that a lot.

Text has different cognitive capacities. If the text is with the work, or functions as part of it — if it feels like the work itself — then it can really offer an expanded reading experience of the work. In the act of making (art, language) we stitch, we bring-together; always tending-to. I love this idea of a mobile language — one that is alive, on foot, itinerant! Messy, vulnerable, feeling, wildening. Re-assembling or shifting words to challenge their boundaries is so much fun.

{} If words build worlds, then in them we can find each other. If we allow it, then there in the stretches of the felt, in our darkness tenderly, they can be our shelter and our hope.

Every month I’ll be asking each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue.

Katrin Koenning’s recommended reading:

I love all of Ellen van Neerven’s work, but Heat and Light — a collection of urgent short stories. Raw, needed, so tender and fierce. They are a favourite poet.

Losing Face by George Haddad — a powerful tale of trauma and survival.

The Undying by Anne Boyer — I read this in early 2020, when death had come and met our lives, and it hit me like a truck. A profound and arresting account of pain, mortality and resilience, as deep as the sea.

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion — an utterly affecting book of grief and loss and longing.

A huge thanks to Katrin Koenning, and to you for reading! You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below.

And if you enjoyed this conversation, please share it — it really helps get the word out.

Thank you Alice and David, a really wonderful piece!

Seriously great interview with David Campany. Super relevant and thought provoking, thank you !