A Conversation with Charlie Engman

Smiling at vulnerability, ecstatic failure, and being pro-mishmash.

There’s a piece of writing advice from Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life that I’ve always loved. She says “spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give now.” In doing so, new and better things will always fill from the bottom of the well.

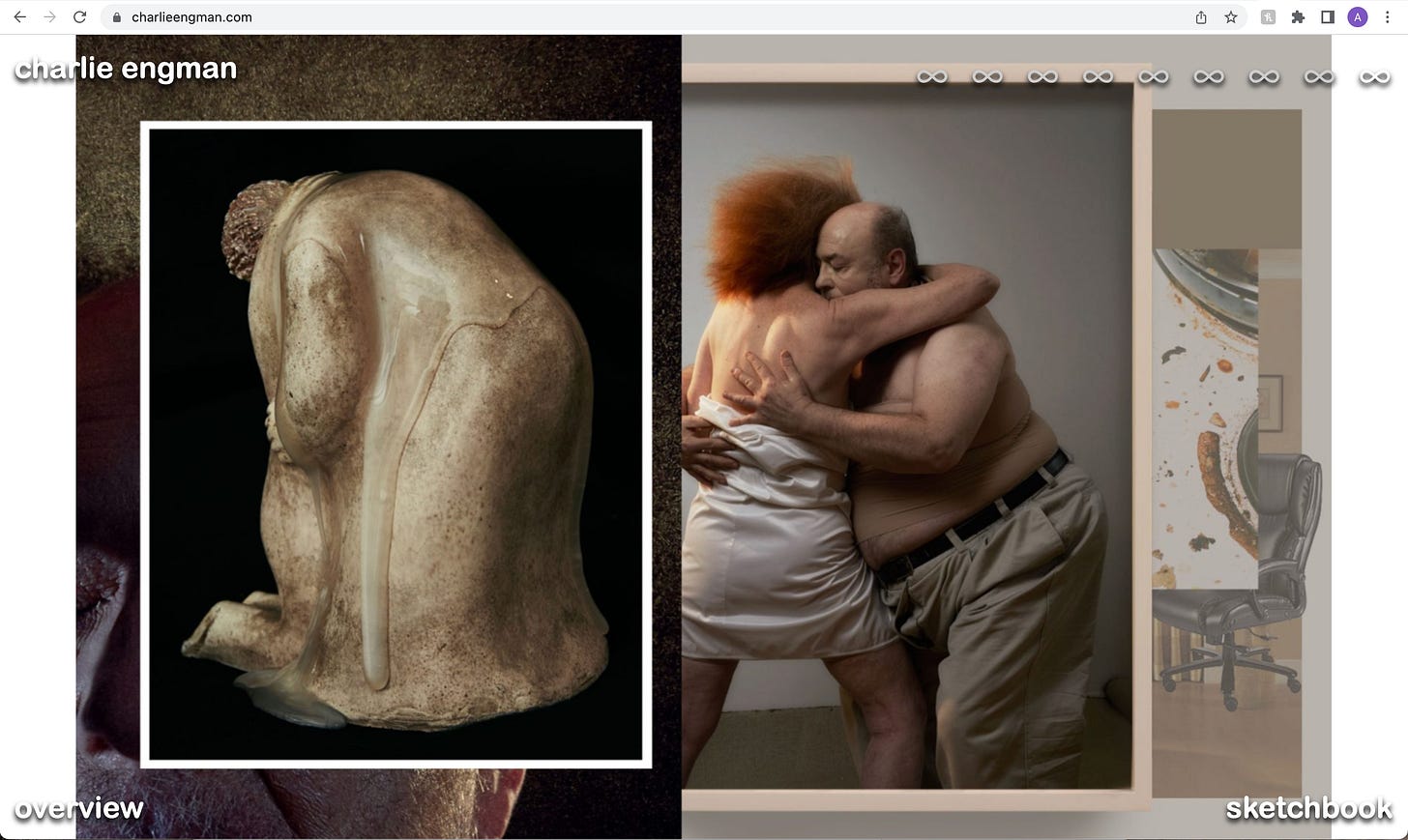

Her words remind me of the work of Charlie Engman. Across art, fashion, and commerce, his work is exhaustively playful, surprising, and multilayered: looking at his photographs, I often find the first prick of humour is followed by a second or third. Things that could be dull or workaday are handled with curiosity and lightness — his website, for example, is a case in point. In his work there’s nothing hoarded, no evasiveness; it’s all laid out on the surface, with generosity and strangeness and costume and colour and line.

Engman’s first book, MOM, came out last year, and is the result of a decade spent collaborating with his mother Kathleen McCain Engman (and contains text from Miranda July and Rachel Cusk — you might have seen Engman’s photographs on the covers of several of the latter’s books). MOM raises plenty of delicate questions about the relationship between mother and son, photographer and subject, image and viewer. Rather than offering answers to any of these questions, though, the book is an imaginative space where they can all run free. (I wrote about MOM much more thoroughly for American Suburb X - you can read that essay here).

What I love about Engman’s work is the expansiveness of his thinking, and the way this expansiveness challenges my own sense of fixedness; the ways I am inclined to delimit and categorise, the distances I put between things. In looking at his work, I see that all these borders and boundaries can be swept away, or at least that art can offer a means of doing so temporarily. Ideas can be mixed and overlaid and expressed in excess, rather than in perfect subtlety and neatness. When my thinking becomes too rigid, when I’m too attached to my concepts, I need only spend time with MOM to throw open a window and let some air into the room; to allow something wilder and more freewheeling for myself, to feel capaciousness once again, a sense of boundless possibility.

Alice Zoo: To start off with, I’d like to ask about your relationship with writing, which I’ve been curious about since I heard you mention taking Alexander Chee’s workshop. In the past I’ve tended to associate your work with the embodied and the physical: with dance, gesture, performance, sculpture; with textures, materials, and surface. All of these subjects lend themselves so well and so naturally to photography (a medium contingent on the outward appearance of things) and are less obviously suited to writing (which excels in exploring areas that photography struggles with, like the intangible and the interior).

On that basis, I’m so interested to hear about the ways that writing forms a part of your thinking and your practice, because — on the face of it, at least — it seems like something of a departure for you, or as though it might open onto new creative or thematic terrain. Could you tell me about what drew you to take that class? Has writing always been a part of your life? Are you writing at the moment?

Charlie Engman: I guess I make less of a meaningful distinction between surface and interior and all that; these things are bound to each other and necessarily act on each other at all times. In my experience, both photography and writing are primarily ways of describing intangible things; both are framing devices that usually represent the context of their subjects more than the subjects themselves. I have always been pro-mishmash, so bringing writing into my practice doesn’t feel like a departure so much as an elaboration.

But of course writing and photography are different! In truth, I had something of a postpartum crisis with photography after I published my most recent photobook, MOM, whose release also happened to coincide with the start of the Covid pandemic. The creative vacuum caused by the book launch and the sudden cessation of life-as-I-knew-it felt like an opportunity to explore new methods of expression, and the solitude and level of control writing seemed to offer appealed to me. I had always been curious about writing but had never allowed myself the time and space it demands. I came to the Alexander Chee class by happenstance; I had read and enjoyed his autobiography, so when I saw he offered a short masterclass on writing auto-fiction, I thought, duh! I had just released a book about my own mother, so auto-fiction felt like a familiar genre. I was surprised to find how much overlap there was between our philosophical and ethical frameworks, particularly regarding the interplay of fantasy and reality and the importance of positioning oneself in ones work. I have subsequently taken several classes at The Warman School, whose queer pedagogy has also really expanded the possibilities of writing for me.

AZ: I wish I felt the same about the (lack of) distinction between photography and writing, which I don’t think has ever been especially useful to me as a dichotomy — I always see this gulf between them which I struggle to leap most of the time, at least in making my own work. Most helpful for me has been imagining writing as thinking, and photography as feeling; which are distinct from one another, kind of, but also — as you say about writing and photography — totally bound together. I really like the idea of seeing them both as ways of describing things, or framing devices, and the idea that writing could be an elaboration rather than using a completely different part of my brain.

I’m also really interested that you were drawn to the solitude and control of writing, because of the spontaneity and surprise that seem to be such important elements in the way you approach making photographs — that sense of allowing things to unfold and unexpected elements to arise. I’m wondering how writing itself has been for you: have you found a way to be as playful in your writing as you have in photography, or have you found the sense of authority and control that writing requires have led to a different artistic approach? And has bringing writing into the mishmash of your broader creative practice changed or affected the way that you’ve been making pictures over the past while, with some of life beginning to return to normal, and as more time has passed since the publication of MOM?

CE: Yes, I work hard to allow and honor spontaneity, surprise, and play in what I do, because they are access routes to vulnerability, which is one of my fundamental interests. I think my work is best when it feels like what I call “ecstatic failure,” where the intentions for the work become overtaken in some interesting way by the process of making or sharing it. That only works in equilibrium, though; spontaneity should be matched with some kind of judiciousness, and vice versa, otherwise they become laziness or neurosis.

I recently read the short story Pet Milk by Stuart Dybek, who apparently wrote it as an attempt to capture the emotional quality of still life in writing. He started from a set of objects (a can of milk et cetera) and allowed the story to wander from there. I’m maybe doing the reverse; writing and editing are ways for me to beckon my more impulsive, intuitive aspects back into the yard. But the belief at the core of my mishmash philosophy is that everything I do, think, and experience informs everything I experience, think, and do, and if playfulness or vulnerability or whatever is my core project, it will express itself in some way, regardless of the method or medium.

AZ: Thanks for sharing that story, I really loved reading it. It’s a nice comparison point for your work — two Chicagoans making work about layers… Considering my previous question, it’s interesting that both Dybek and Kate Walbert, in the podcast discussion, have spoken about moments of their writing beginning to surprise them: the idea of the writing escaping the preconceived intentions of the writer and transforming, and the writer’s role being simply to follow, or allow. This seems to reflect the way you refer to your core project: “it will express itself in some way”, as though it’s something with its own will, distinct from your own. I suppose that’s one reason why both spontaneity and judiciousness are necessary: first the setting free, and then the reigning in.

I’d like to think a bit more about vulnerability. It’s clear how crucial it was in MOM, not only in terms of the ways that you were depicting your mom, but also as a condition of the project as a whole: the trust required for such an exhaustive body of work made over the course of ten years. The idea of vulnerability comes up a lot in the context of the autofictional narrator too: how much the self is exposed, or hidden, and whether its revelation is truthful, partial, or deceptive. Do you feel a level of personal vulnerability or exposure in the course of making or sharing work (photographing, writing, creative directing, etc)? You mentioned earlier, for example, the importance of positioning oneself — could you tell me some more about that?

CE: I once heard the artist Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. say “visibility is not a prize,” and I think about that a lot. Visibility is its own kind of vulnerability. Offering any part of yourself for the consideration of others is as exposing as it is empowering. In working with Mom, I really confronted this duality; she submitted herself so fully to me and the process of making the work that the pendulum swung all the way around from submission to domination, whereby I felt almost subjugated to her submissiveness — I felt beholden to it, responsible for it, in service to it. Partially through that work, I came to understand that vulnerability is a primary, inevitable experience, and what’s important is how you meet it. Do you avoid, hide, and antagonize it, or do you embrace, nurture, and smile at it.

This is, in some sense, what I mean by positioning oneself. It is not about enumerating certain biographical details or moral inclinations or prostrating oneself to some social propriety. It’s about looking deeply at oneself and doing one’s best to act in accordance with what one sees there. I often see people positioning themselves as a means of defense, a kind of prophylactic apology or guard against the vulnerability of visibility, but I see it as an opportunity to do the opposite: to invite the universal experience of vulnerability and acknowledge and enjoy one’s own unique relationship to it. If this is done with maximum humility and patience and the right balance of judiciousness and abandon, it can be an act of radical generosity to include others in what comes out of that work. But it is an ever-ongoing process, and it is work, the hardest work.

AZ: All of that makes me think about the visibility of process in your work, especially MOM, and the collapsing of hierarchies: the screenshots and collaging; some of the “best” images hardly seen, pinned on a pinboard or bisected by the gutter. It’s rare to have access to the insides of a work like that, and it seems like a very particular kind of creative vulnerability that’s sort of toppling the authority of the photographer in favour of something looser and more elemental. And I think it’s important, as you point out, that this process speaks not only to the artwork itself but to the relationships outside it, and the ethics that underpin it — MOM’s not a closed circuit, artwork for its own sake, but is also the documentation of a process of mutual exposure. The thoughtful viewer then considers their own biases and projections exposed by looking at a work like MOM, which is layered with different kinds of challenges to all kinds of conventions, social and artistic — so there’s a third layer of vulnerability there too, that which the viewer brings.

Finally, I wanted to ask about your study of Japanese and Korean, something I’m personally especially curious about because I also studied languages. How do you think learning other languages, and then going to live in places so different from your native one, has informed the values and sensibilities we’ve been speaking about? I’m thinking about the idea that a second language gives us renewed or different access to ourselves; and the humility involved in learning to speak and express oneself again using, at first, only the very basics; and your movement between mediums and contexts in your work (whether personal or commercial); and then arriving at a writing practice after a decade of working on MOM.

CE: Yes, to your first point: I like to illustrate the process of my work wherever possible because it is a way for me to access the generosity I mentioned earlier. It’s generous to my audience to trust them with those tender inner-workings, and it’s generous to myself to allow the process to be enough. In any case, the process is usually more interesting to me than the product, though I sometimes catch myself masking insecurity about a product by fetishizing the process, and knowing and accepting the difference is the hard work of integrity.

To your questions about language: it’s important to position oneself but also to have a light touch about that position — to see it as one star in a constellation of many stars, so to speak — and, as you said, learning a different language and culture can help access that kind of humility. I began learning Japanese at a relatively early age through very close family friends (Korean came later), and the experience of coming into this knowledge was strangely parallel to the experience of coming into my queerness, in that both experiences made me confront the constructed aspects of the sociocultural landscape I inhabited and forced me to cross-reference every image and item of information I encountered against my own personal experience. Femininity, for example, meant something very different in Tokyo than it did in Chicago than it did to me. Seeing that these different perspectives were coextensive and equally valid helped me understand that I had choice in how I looked at things but also that my choices were conditioned by things I could not choose, like my upbringing or the opinions of others. I saw that I was vulnerable to the things I could not choose but that there was also power in that vulnerability, like the power Mom demonstrates in our work together. There’s a beautiful mutuality there that I’m constantly working towards.

Every month I’ll be asking each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue.

Charlie Engman’s recommended reading:

“I think everyone should read Brontez Purnell. His recent book 100 Boyfriends is a joy.”

A huge thanks to Charlie Engman, and to you for reading! You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below.

And if you enjoyed this conversation, please share it — it really helps get the word out.

Brilliant read!

Of course, I’m logging in as the first comment.

Charlie, thank you always for your fierce generosity.

Alice, I am ever astounded by your mind.

I can’t wait to see what you next interrogate.