We’re used to seeing photographs about desire, especially because desire is the native language of fashion and commerce. Fear is a far less common emotional tone for photographs. For the casual photographer, at least — the person working outside the specialised contexts of photojournalism, conflict photography, medical photography, etc — it’s unusual that we get close enough to the things that frighten us to photograph them; more frequently we want to turn away from them completely. Not so in Bedfellow, the brilliant, disturbing first monograph by Caroline Tompkins, which is about both things at once.

The book collects images from the past five years of Tompkins’ work: photographs that reflect her experiences of desire, sexuality, pleasure, danger, and the often absurdly precarious-feeling stakes of contemporary heterosexual womanhood. As a body of work, it presents the viewer with a set of questions and tensions rather than conclusions. “I always feel like I’m experiencing something on two planes – the woman from Ohio and the woman from New York, the male and the female, the American and the outsider,” Tompkins has said. Bedfellow similarly operates on two planes, showing us the ways that it’s possible to fear something as much as to want it, and that fear can be as much a catalyst for desire as the potential for pleasure.

Tompkins’ vision is pin-sharp, in both image and text — she is an excellent, effervescent writer as well as a photographer, and the book begins with an extended personal narrative in which she describes a lifetime’s worth of absurd and terrible experiences relating to men and sex. She’s self-deprecating, but never in a way that invites pity; she’s too funny for that. Humour and surprise are excellent distractions, and the emotional freight of it all almost slips past without notice, just like the way that her pictures look so good that you don’t realise how unsettled they’ve made you until it’s too late. For all her incisiveness, perhaps Tompkins’ best trick is seeming so casual about it.

While I was putting this newsletter together, I kept thinking of that old line: “everything in the world is about sex except sex. Sex is about power.” For me, a sense of Tompkins’ immense potency is what I keep returning to: her ability to gather all of these deeply ambivalent experiences on these pages and bend them to her creative will like a magician. Though the book examines fear and desire — and sexuality, pleasure, abuse, bodies, men, women — in the end power, to me, feels like the essential matter and substance of Bedfellow, the blood pooling on its belly.

Alice Zoo: In a few different interviews you've mentioned thinking of the images that ended up in Bedfellow as “heaven and hell pictures”. Could you tell me some more about that?

Caroline Tompkins: When I was in college, I was making pictures of men who catcalled me, and while I don't make pictures like that anymore, I think it was an acknowledgment of a certain fear I felt just by entering the public space. In the years after I finished school, I only wanted to make pictures of my lust and desire for men. I didn't feel like I had a proper reference point for those kinds of images made by a woman, and when I started making them, I noticed a lot of them were unsettling or even scary.

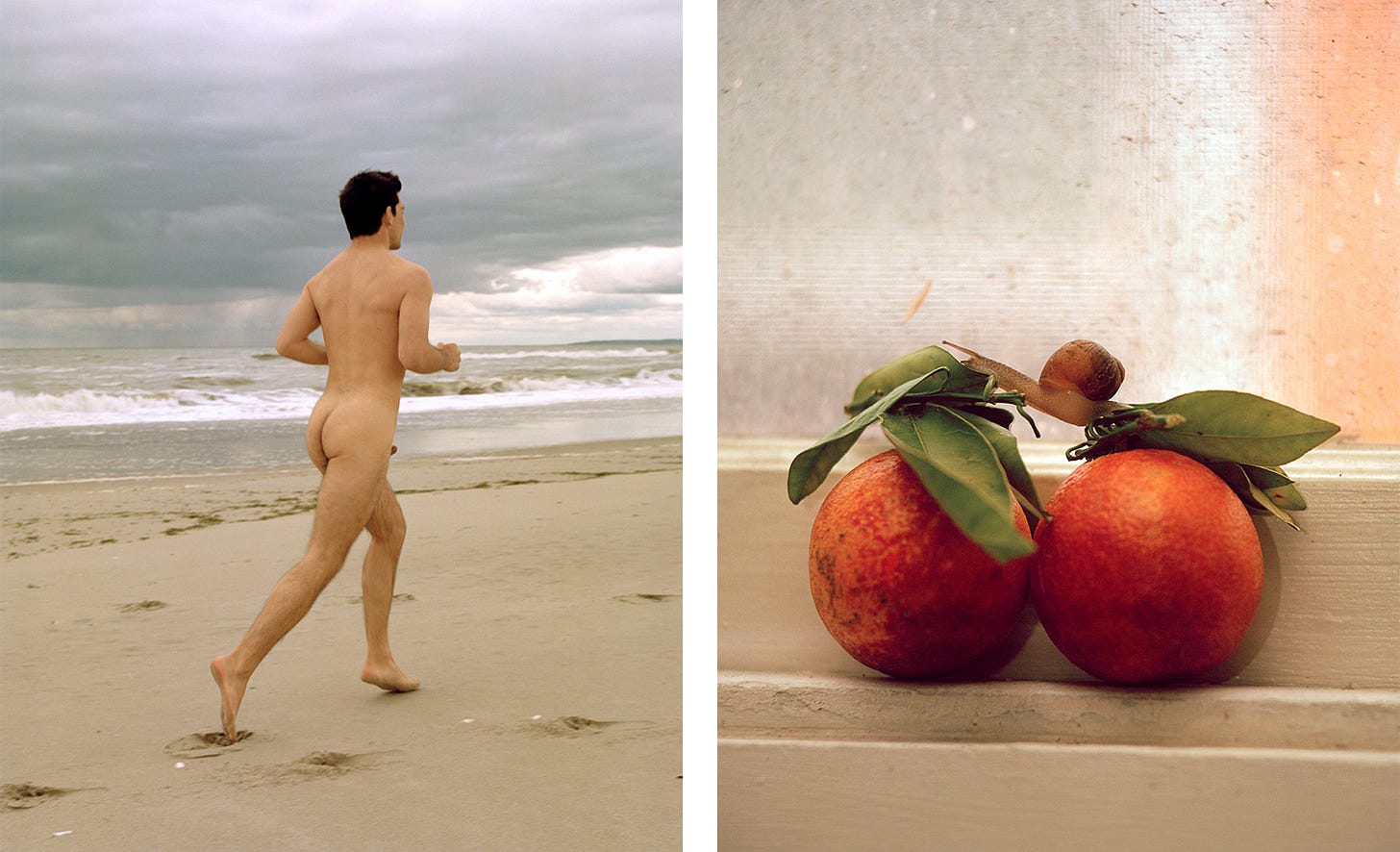

So this got me thinking about pictures of men and women as sexual objects. When we see images of men being sexually objectified, we often see the images as homoerotic, and when we see pictures of women, we also see them as being taken by a man. So what does a sexualized picture of a man taken by a woman look like?

I started to think about the way my female friends and I interacted with dating and having sex. We told each other where we were going to be after a date. We carried mace. We were in abusive relationships. We got restraining orders. So many of these things felt so normal that once you started to unravel them, you realized how deranged it all is.

Of course, there’s the other part of this which is that I enjoy sex and I desire men. I felt so alienated by the “men are trash” narrative on the internet. This experience that I have, that I think a lot of women have, is so dichotomous. And in thinking back to my historical reference points, I gathered that the reason sexualized images of men and women are seen as taken by a man is because men still own objectification, but images made by women acknowledge their fear of them, even if it’s slight.

Back to the heaven and hell pictures, I wanted the pictures to exist on these two extremes to represent the spectrum of this experience. The heaven pictures are these utopian views of intimacy, pastoral landscape, and domestic scenes, and the hell images are scary boners, balls strung up to a car, or a phallic flower surrounded by cactus needles. When seen together, you feel a sort of anxious romance.

AZ: I really like the way that Bedfellow collapses these binaries — it feels like a much truer vision of sex and sexuality than images that are straightforwardly idealised or desirous, that intend to be sexy or appealing in the familiar ways. It’s far more accurate in its reflection of the way that in sex there’s such a thin line between desire and disgust, or desire and fear, or power and disempowerment, etc.

I’d like to talk a bit more about fear, though, and the way you talk about being drawn to photographing things that frighten you or make you uncomfortable. I wondered what effect photographing these things — the hell pictures, the catcallers — had on your fears around them? Do you feel less afraid, or braver? Are those things more inert than they might’ve been, or otherwise transformed? Does the presence of the camera have an effect on you, either at the time, or after?

CT: Because I take pictures for a living in an editorial and commercial context, I find that I can get so indifferent about photography so quickly. Not about pictures that exist in books or exhibitions, but the pictures I have to make to buy all the things I need to buy. What I’m getting at is that I’m in a constant search for a strong emotion when making pictures. My favorite pictures always make me feel a bit shaky after. I’m constantly searching for that I can’t believe that just happened moment. I think that’s why I lean into these feelings of uncomfort — just to feel something, you know?

I want to be surprised by pictures all of the time but surprise isn’t a sustainable way of living. Fear has always been a good barometer for what’s important to me, and in turn what might be important to make work about. Unfortunately, in most parts of my life, fear has always been a good motivator.

I’ve always used photography as a sort of permission slip to be somewhere and to follow a desire. If I use photography to make a picture of a boy I have a crush on, I'm leaning into a fear, and that fear feels quite similar to the fear of photographing a catcaller. Ultimately, taking the picture doesn’t make me less afraid, but the camera offers a way to translate the message.

Photography has been a way for me to understand the world around me too. A way of relating to others. Especially the contents of this book, women often experience these things on an individual level. I started feeling like, wait, why aren’t we all upset about this? So while I'm not much of a grassroots organizer, photography is my preferred method of transcription.

AZ: It’s really interesting how closely fear and desire sit together in your approach to your work. Your book explores fear and desire for men, but those impulses are essential to your creative work too — almost like men and sexuality are an analogy for the creative process, a life committed to art. I hadn’t thought of that before this conversation, even though I’ve looked at the book many times. Desire for men, desire for experience, desire to create, all different shades of the same foundational impulse.

And I know what you mean about surprise. I feel like the thing I like most in photographs is often that prick, bite, or edge, where something beautiful starts to ferment. A picture that’s beautiful in the way that pickles are delicious, or anchovies. I feel that’s getting rarer, especially as the lines between commercial and art practice are getting more blurred. Everything’s starting to look very nice, and stopping there. Everything’s a peach.

Surprise is hard to come by and hard to cultivate. In my own work, I struggle against the way that photography seems to demand so much precision and control, and I find it really hard to let go of those things (when I do, the work’s better, obviously). This is on my mind because I wrote about it recently, but I wondered what you think about the idea of control in relation to photography? Or, how do you maintain control, while inviting surprise? You talk about photography as something that facilitates so much for you — permission, understanding, communication — but are there ever times when its limitations frustrate you? Do you ever feel like you’re straining against something?

CT: Oh my god yeah, I'm always struggling. I’m constantly wishing I could get something out of someone that I don't know how to ask for, or worse, knowing I want to ask for something but not knowing what it is to ask. I want to say Okay, now surprise me with this one! When I was photographing the leeches, my boyfriend Kevin was helping me with it and said to the subject (who is Kevin’s best friend), “okay now grab your cock”. I looked at Kevin with bewilderment because he had read my mind. It was exactly what I wanted but was unable to say.

I’ve been thinking lately that a lot of it comes from the story I wrote about in the forward of the book (the one where my college boyfriend uploaded sexually explicit photos of me on the internet without my knowledge). It’s created a lot of apprehension for me. It’s made me timid and paralyzed to ask for too much. I keep thinking “I need to be more Italian”, but instead I think, “what if they change their mind about this later.” At one point in making this work, I reached out to a bunch of exhibitionists in the kink community just because I knew being naked on the internet would play deeper into their fantasy. I didn't end up photographing any of them but at the time it felt like the only salve to this problem.

I’ve been channeling more control lately, like having things set up and sketched out. The only solution I found to maintaining surprise is to let yourself be open to it. As in, set the basic perimeters but allow yourself to be inspired by what the other person brings to it. There’s an image of a man with a boner in the book. I had found a reference photo in an amateur porn bin that I wanted to recreate. The reference photo was a man with his underwear in front of a curtain. When I went to take the photo, the subject pulled his underwear down and had this boner. We both didn’t really say anything, and I just kept taking pictures.

AZ: First of all, I just want to say that I’m so sorry that happened to you. That should never happen to anyone; it was hard to read about. And — though it’s totally understandable — I also think it’s fascinating to hear you describe yourself as timid, because your work is so bold, and feels really effortlessly sensual and open, none of which qualities you’d associate with paralysis. It makes me think of that process whereby we overcompensate for our hangups to the point that those qualities in us seem unthinkable to other people, the opposite seeming true instead — the insides not matching the outsides. I remember I photographed someone a few years ago who kept apologising for their cluttered, messy house, but the house itself was completely pristine, almost bare.

The way you write about that experience in the introduction to the book is uncanny, because the subject matter is so disturbing, but the prose is funny and charming. I’ve been dying to ask you about your writing. Like your pictures, it feels very bold, very effortless. What do you feel about writing? Does it feel like an offshoot of your photography, or totally separate from it, or do you see them both as part of a broader artistic practice? Do you think of yourself as a writer as well as a photographer? Do you care about it in the same way?

CT: Yeah, I think similar to what you said about the person with the clean house – I can use the writing to be whoever I want to be, not necessarily who I am. I don’t really write in my free time, and sometimes I think I’m trying to preserve my naivety. I often feel like I know too much about photography. It becomes a prison of knowledge, and I’m jealous of the 23-year-old me that knew just enough to make a good photo but not enough to judge myself for it. With photography, I feel like if I just took a few more photos, I would unveil some parts of myself I haven’t found yet. With writing, I have a certain protection over my thoughts, memories, jokes, etc. As I’m writing this, I’m realizing that my photography career could learn something from my writing career and vice versa…

But in regards to the book, I thought of the writing as a companion to the images in a way that was more engaging than, “So these pictures are about…” If you don’t understand the thesis of the work at first flip through, you should mostly understand it by reading the intro. What really excited me about writing it was the ability to control the narrative of hardship, to be nuanced, to not be a victim on a soapbox. Like yes, it’s objectively bad to have lots of sexually explicit photos of you on the internet, it’s those big words like victim and abuse, but I don’t care about the sad story. I’ve grieved the sad story. What’s more powerful than being funny about it?

AZ: And by framing the book in these explicitly personal, subjective terms, the emotional stakes are raised for the viewer/reader. The narrative isn’t abstract and theoretical, nor is it straightforwardly documentary, and I feel like that’s another reason that the book feels so engaging: that it’s tied so closely to the personal, and all of the character and nuance that come from being specific.

Another way that you implicate yourself in the work is by the inclusion of self portraits. I remember reading this article when it was published and finding it so striking, your description of your relationship to your body as being ongoing and lifelong, “like grief”. I wondered how you felt about including yourself in the book, whether it was obvious from the outset that you’d do so, or whether it was a decision you came to later? How do you feel about making portraits of yourself as compared with photographing someone else, and then how do you relate to those images afterwards?

CT: Something I often think about with self-portraiture is that it’s easy. I’m the easiest subject I’ll ever work with! I’m already there, willing, and able. I don’t need to ask myself for permission or worry about someone regretting it later. I can think of something and execute it in a day.

Similar to the writing, when I look at the pictures of myself, they’re just stand-ins for an experience or an idea I'm trying to get across, but it’s not me, not really. Those are pictures of my friend, Caroline.

It was also important for me to have skin in the game, literally and figuratively. I wanted to create equity with my subjects. It just seemed fair that way? With this work, I kept trying to speak for the entirety of women — all women experience this — but the more I did that, the more I realized how alienating that is. I might as well get personal and allow people to meet me where they’re at. The viewer can choose how they relate.

Every month I’ll be asking each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue.

Caroline Tompkin’s recommended reading:

Circle Mirror Transformation — Annie Baker

How To Do Nothing — Jenny Odell

Why People Photograph — Robert Adams

A huge thanks to Caroline Tompkins, and to you for reading. You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below:

This format is so cool! Thank you for this poignant interview ...!