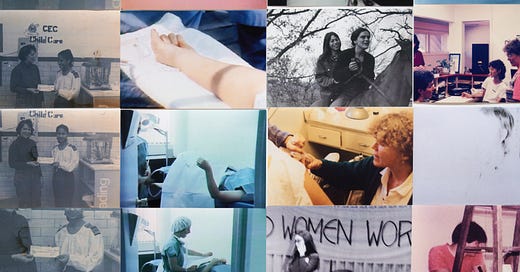

“Abortion care is work,” writes Carmen Winant, “which is to say that it is, and looks, entirely regular.” Currently on display at the Whitney Biennial, and forthcoming as an artist’s book with SPBH/MACK, Winant’s new work The last safe abortion gathers 2,700 photographs from archives held by abortion clinics in the United States, as well as her own original photographs — of the staff, the volunteers, the answering of phones, the office birthday parties, the rallies, the front desks.

Photography does not often attend to the regular, and so it feels miraculous that many of these images exist at all. Who was moved to photograph the chairs in an empty waiting room, the clocks on the office wall? And why? In Winant’s tender arrangement, we see all of these particulars, the unremarkable spaces and materials surrounding a procedure that could, in other circumstances, cost a person their life. In the photographs’ tentativeness and imperfections — the majority of them are vernacular, non-professional, often fogged or off-kilter — we are reminded that the whole network is under threat, the clinics closing one by one in a post-Roe America.

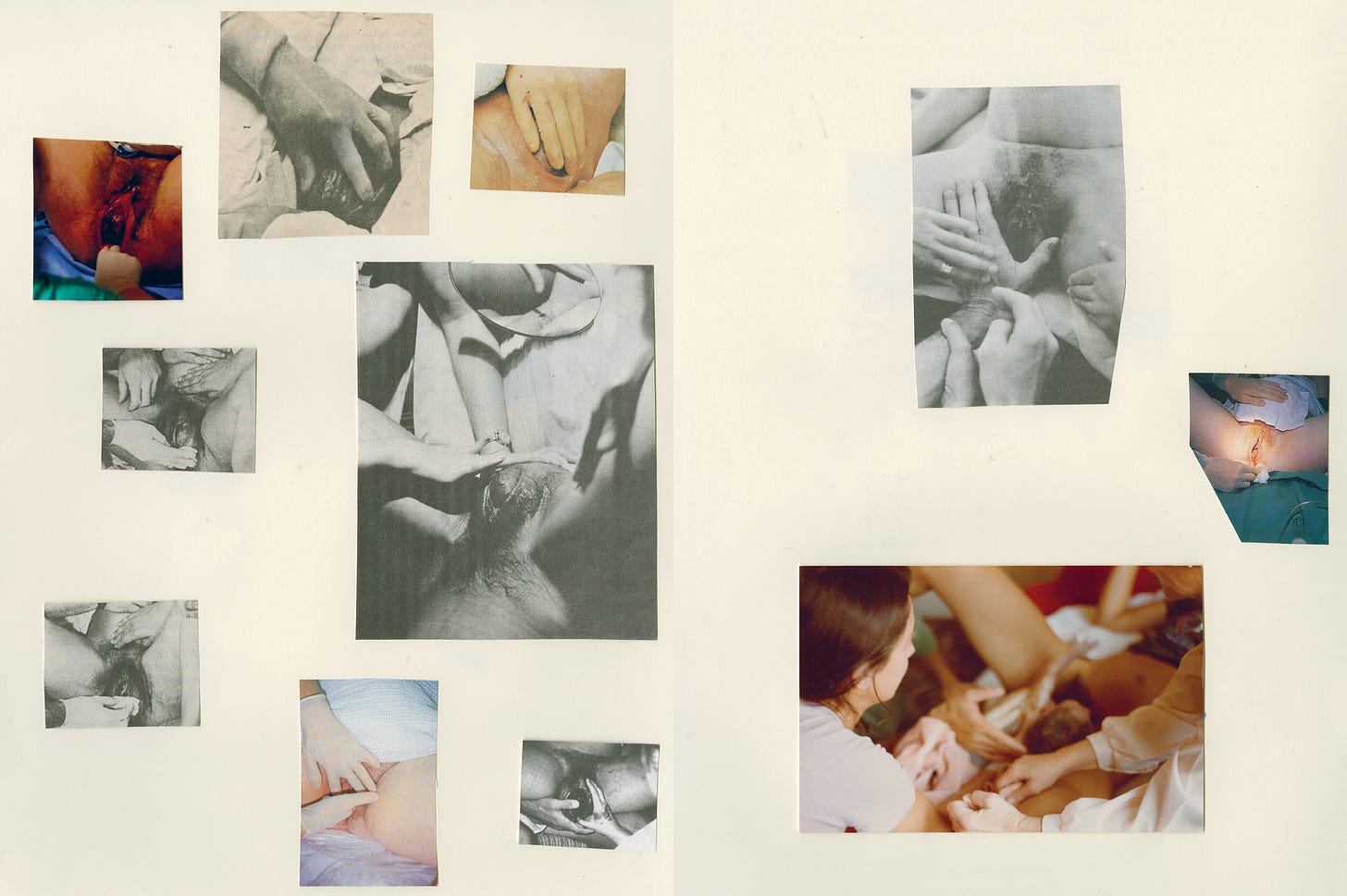

One of Winant’s strategies as a visual artist is quantity. She accumulates and displays such a profusion of images that not to attend to them, not to respond to them, becomes impossible. This strategy is applied differently from work to work, though, and so each copiousness has a different effect. With My Birth, at MoMA in 2018, the effect was awe and shock (and then a kind of shame, that such images should be shocking): the walls of a gallery corridor crowded with thousands of pictures of birth, babies crowning from vulvas on delicate paper cutouts taped to the wall.

In My Birth, Winant wrote of the desire to describe the ineffable: “Like every good subject, [birth] fails me. How do you speak in a language that has no words?” — as though confrontation with so many photographs might translate some of the intensity of birth inaccessible by text, or by a single image. The quantity of images in The last safe abortion has a different effect; to me, it feels rhythmic and vast, like an ocean, describing not intensity but expansiveness: these women are here in the world, have been here in the world, caring and providing for one another for decades. They will continue to do so.

As I spent time with this book (and it is a book that has come to feel talismanic to me, that I have been carrying around with me, that heartens and consoles), I was thinking not only about abortion care but also about the feminist vision of photography that Winant’s larger project proposes. Photographing — so often thought of as an act of dominion — can also be an act of care, of maintenance, of guardianship and partnership. The act of taking these photographs, the act of keeping and preserving them by the clinics, Winant’s own warm and careful stewarding and curation— all of these are undertakings grounded in generous mutuality.

What might an ecosystem of art founded on these principles — rather than the imperatives of capitalism and patriarchy — look like? And what might such a system make possible? The last safe abortion comes to seem like a vision of that other world, so rarely depicted in this one.

Our conversation has been condensed and edited.

Content note: this newsletter contains explicit images of childbirth.

Alice Zoo: I’d like to start with your decision to focus on abortion care, as distinct from abortion. I wondered how you came to that decision, and why.

Carmen Winant: It’s not a secret that the anti-abortion movement has weaponised photography, for as many decades as they have, as a decisive and intentional strategy. I work on college campus in the Midwest region of the United States; there are anti-abortion posterboards that I encounter, sometimes on a multi-week basis, and have to circumnavigate on my way to the art building where I teach classes in photography — so I’m confronting the manner in which this movement and these agitators are utilising our shared medium. And so I began to ask myself, in the early stages of the project: what is a way to countermand these kinds of photographs?

Another way to ask that question is: why has our movement — which was once called pro-choice, and is now more often called reproductive justice, for a number of reasons — been so shy or reluctant or unknowing in its relationship to photographs? And when they do appear, they’re often laced with trauma narratives. The more I thought, ok, what is not necessarily the inverse of what they’re doing, but a way to create a counterimagination to it? — the more I felt like, oh, that’s pictures of care. Because in these pictures of so-called aborted foetuses — and not just the gory pictures, but also the Lennart Nilsson, hyper-sensual, “space man” pictures of the floating foetuses — the mother or pregnant person is nowhere to be seen. She’s completely detached from the experience. It has no reference point to science, labour, care — it’s just this floating foetus.

And so I began to think increasingly about how important it was to put those people and that act back in the frame. And in so doing, I had to confront the fact that I was meeting a scream with a whisper. There’s never going to be anything that I could make as sensational and graphic and attention grabbing as a picture of — I mean, this is total misinformation, but of “an aborted foetus”. And that’s ultimately ok. That is what it has to be, necessarily; not just abortion care, but all care works this way. It’s quiet. Answering the hotline, or sterilising medical equipment, or throwing a staff birthday party; these are not inherently photographic acts. And that’s really what interested me about them the most.

AZ: It’s also an interesting counterpoint to My Birth, which had an immediately arresting, visceral quality, especially compared with this very measured, consciously non-sensational work.

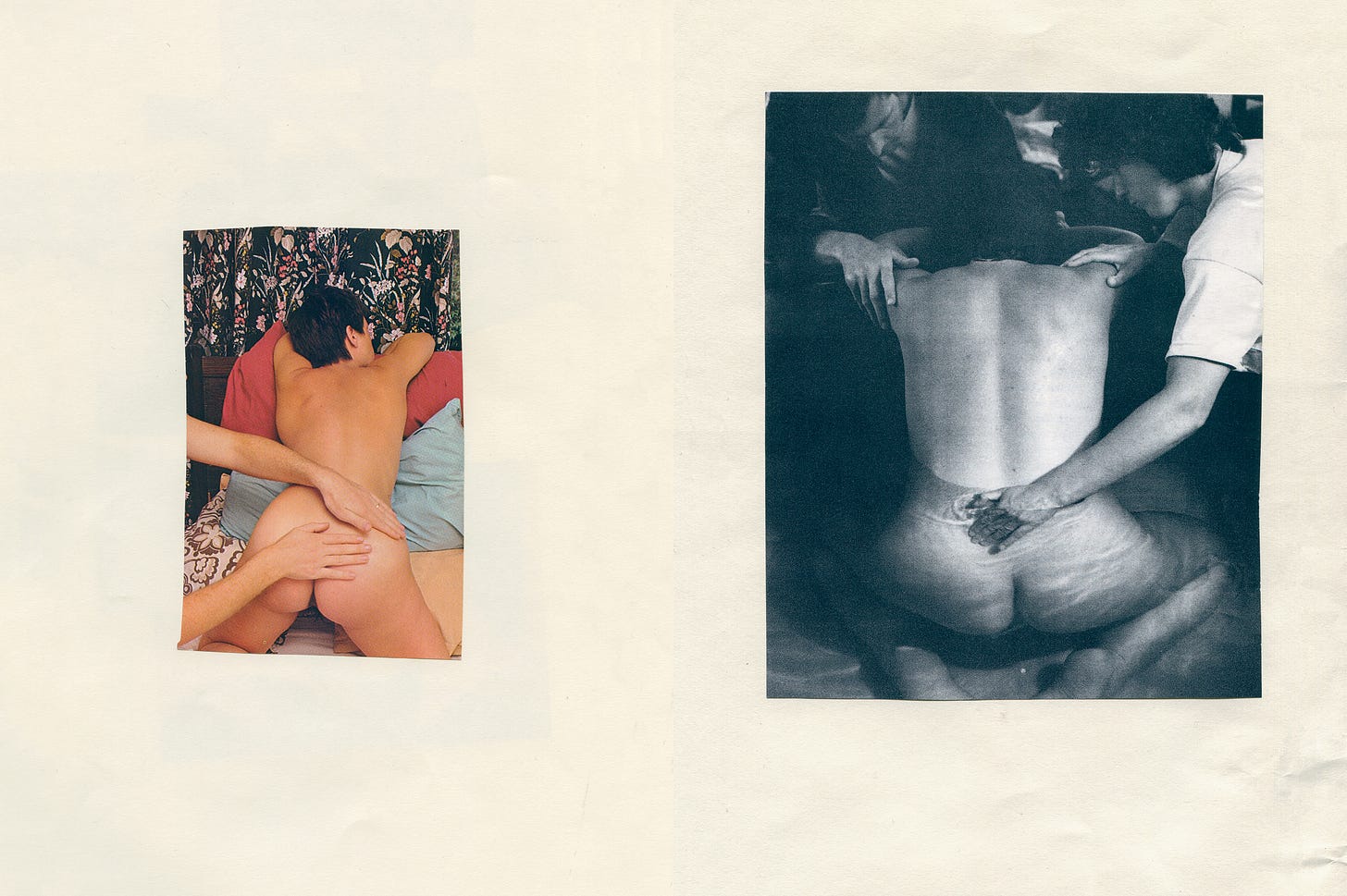

CW: I agree. I was just talking about countermanding the graphic and attention-grabbing kinds of photographs — and what could be more attention-grabbing than a baby crowning, or a body coming out of another body? And ultimately what I find myself gravitating towards as I return to that work, is — surprise, surprise — all of the birth workers that are there, and support staff, and the tenderness and specificity of their gestures. But I couldn’t have named that for myself at the time, and it’s really only looking back, and with a project in between in and around domestic violence advocacy and support workers, that I can really appreciate it as an arc around feminist healthcare workers. While things are ongoing, it’s much messier. I think it’s easier to name that retrospectively. And so in coming into the consciousness that that was the locus of my interest, reaching as far back as My Birth in 2018, I was able to centre it more deliberately in this project.

AZ: Have you read How to Do Nothing?

CW: I have, I love that book.

AZ: I was thinking about that book a lot while I spent time with this work, and what Odell writes about the priorities of capitalism — of constant growth, and innovation — and how they don’t leave much room for the acknowledgement or depiction of care and maintenance work.

CW: Right, which are in some way anti-capitalist activities, but also hold up capitalism.

AZ: In The last safe abortion you write: “I am interested in how we build kin,” and then, “What if building social alliances (also known as friendships) was the outcome of the work and not only its subject?”

I’m curious to hear more about that process — how it began, what it looked like, and how those relationships continue now that the work has been made.

CW: I write about this a little bit in the book, about how looking back I consider my earlier work to be much more extractive, and problematic, for that reason. This instinct — as so many archives’ researchers are inclined — to go in, root around, and find the material that you need. That’s not a bad thing; that’s how we make sense of archives, it’s the reason we maintain archives. But my work is about social coalition-building. It’s about how feminist community networks are developed, how solidarity is built in service of a larger social movement, and so it just began to feel increasingly isolating and nonsensical to work that way. Again, I can talk about this now as if I had it all worked out; it’s really something that happened slowly over time, that I’m only coming awake to now in a lot of ways.

Because, too, I’m working with material largely from the mid-to-late twentieth century, a lot of these people are alive — or their daughter, or their niece who’s managing their material or their estate or what was in their closet — and so it felt like these folks are actually accessible. What an interesting and obvious prospect: that building a relationship is not only a means to an end. How could I think about that more deeply as it comes to matters of reciprocity and long term friendships? So it manifests in lots of different directions, everything from really functional questions around scanning material for use in the centres’ own marketing and comms, building an internal database so that they can access it; to helping folks apply for grants, and placing their material in public libraries.

There are practical things like that, but there’s also just knowing folks, you know? And continuing to demonstrate curiosity and investment, not as a favour, but because that’s what it is to sustain relationships. That can be particularly hard to talk about in an interview or put into a slideshow, because it’s not demonstrative in the same way; but it has really become the engine of my practice in recent years.

AZ: I really admire that. You speak a lot about materiality, and making the labour of your work visible, and this feels like the logical endpoint of that commitment — which is that the work is actually in the world, is in being in relationship with other people. I feel that art often doesn’t go that far. Often it remains in a space where it might be talking about materiality and labour, but refers only to itself.

CW: Well, you’re describing a major existential crisis of mine, this question of how far art can go. At what point can it be functional — really, actually serviceable — and at what point does it cease to do that? Another way to ask that question is: is art enough? And for me the answer’s always no. I feel like it always has to be paired with real groundwork. And I’m either more or less successful in doing that myself, but I have a healthy ambivalence about it, which drives me to its outer edges of possibility.

AZ: Could you tell me about putting yourself into this work? How did it feel?

CW: It wasn’t how I started the project. Initially I thought I would do something a little bit more in my wheelhouse. I was going to the clinics and looking through their archives, as well as going to institutional archives, special collections, and universities.

I thought that I would pull from those photographs, doing what I’m most interested in doing, which is creating a visual lexicon where there’s otherwise a vacuum. Where were these pictures of abortion care? I’d never seen them before. And as with the projects around birth and domestic violence, that was really my initial goal and logic. It’s all so decentralised.

And then how did I start taking pictures of myself? I was photographing myself to finish off the roll — I would get back to the hotel room, if I was travelling, and I would have four more frames left, and I would photograph myself. And I showed those pictures, almost by accident, to the curator on the project, Casey Riley, who’s really so brilliant, a feminist visionary, and she encouraged me to not only keep taking those pictures, but to include them in the project. I’ve always felt really reticent to have my fingerprints anywhere — I don’t want to make myself the protagonist in a story that I don’t belong to, that I was not otherwise around for, and that is definitionally about a broad base community and network. Centering myself has always felt very weird, which is why I’ve never done it.

At Casey’s urging I continued to photograph myself, sometimes inside of the clinics, the idea being that I was there, whether or not I wanted to name it. I’m the one who’s making editorial decisions about which pictures I want to include, how I want to sequence them, what I want to exclude — and not only that, but I’m there historically, as a beneficiary of 50, 60 plus years of the work of these folks who I’m photographing, and inheriting pictures from. And so the idea was to name myself in both of those ways, and also demonstrate how abortion care looks and exists in the present moment; that it’s not an anachronistic, bygone question. As a movement, and also as a matter of healthcare, this is existing in the present tense — and the only way to show that was to make my own pictures.

AZ: The work includes images of yours that others might exclude — camera mishaps, and so on — and I’ve been wondering if you could tell me about the decision to include those so-called mistakes. And then, as an extension of that question, what is interesting to you about failure as an idea? What does it signify for you?

CW: In retaining those photographs I wanted to do a couple of things. First, I wanted to point to my own process inside of the making. You referred earlier to the ways I try to hold onto and demonstrate labour, in a number of ways — not just as a subject or idea, but as a demonstrative process, in the material presentation itself. And so, to me, the mistakes — be they over- or underexposed, setting to the wrong ISO, photographing on film that’s not meant to be photographed under tungsten lights — there are any number of errors I can make, as we know. It felt to me like a way to point to process, labour, intention, floundering, regrouping; that this is what the artist does, this is what the activist does, this is what the feminist healthcare worker does; it’s one foot after the next.

The other thing is that the archives themselves have all these kinds of pictures. I was really moved by this. It’s largely pictures of women — and they are almost all women — in clinics, going about these really functional tasks, but they also keep the blurry pictures, and then somebody brings the camera home, and they’re photographing their kids, and the sky. There are so many “incorrect” moves throughout the archives themselves, and I wanted to not just mirror that, but signal my appreciation for the fullness of that picture.

As for the question of failure — I am really interested in that, in all sorts of ways. I talk to my students about it constantly: what is this question of productive failure? I’ve always operated that way in the studio. I think of myself as a studio artist as much as a photographer, if not more so; and it’s always been a matter of coming in contact with the work with my body, and trying and failing, learning, regrouping, rejiggering, and so I’ve really come to not just appreciate that as a part of the process, but work to intentionally fold it into the messaging around the work.

AZ: In My Birth you spoke about your difficulty in finding people of colour in the archives you were working with; you mentioned this in the wall text, and made this omission a part of the work. How were you thinking about intersectionality and representation in the course of making The last safe abortion?

CW: I learned a lot from working on My Birth. It’s such a meaningful project for me, but I feel like it was a really imperfect one, and an imperfect solution that I arrived at — naming the omissions over and over. That achieved something, but I don’t know if it achieved enough. And I worry, still, about the ways in which I stood to reinforce certain tropes around whiteness and motherhood, and so many other things like ableism, and heteronormativity, and so forth. And one thing that I learned — and again, this is something that I wasn’t so intentional about at the time — but I think now that I have my head above water I can say, in retrospect, that I really wanted to go to the places where intersectional exchange was happening already. I think that’s also how I found myself, for instance, in the domestic violence support worker project, because that is a space that was ignored by a lot of feminists in the second wave.

That is a space that is so multiracial, intergenerational, transnational; it’s all happening already, and was happening before we had words for it. And I feel that way to a certain extent around abortion care in the United States. I was amazed by the diversity of the identity positions represented, the multiraciality in the photographs themselves.

It was incredibly moving to encounter the intersectional solidarity that’s so clearly represented in the pictures, not only in the patients — so few of whom are represented, because one needs permission to photograph patients — but also in the providers. I don’t want to flatten out this history, it is complicated, and for so long the “pro-choice” movement was a middle class white woman’s game in this country; but since the mid-80s it’s really been led by Black women, and women of colour, and that is hugely represented in the pictures. And not just the abortion movement, but also reproductive justice is entirely Black women-led.

And so that’s just to say that it’s evolving, and I really felt I was engaged in propagating an intersectional movement in and of itself, not just as it comes to race and identity position, but also huge intergenerational inheritances and collaboration. I felt so honoured to be coming in contact with that material, and to be centering it in one place, where it’s otherwise been atomised throughout these various regions, clinics, and institutions.

AZ: In an interview from around the time of My Birth, you said “I want to see the labor on the surface of the work, as the work. I want the artist to present as a self-made expert, and I want to sense that process of self-making in the thing they do.” I’m interested in the idea of self-making in art — could you tell me some more about that?

CW: What comes to mind is permission and vulnerability. Let me put it this way: I was working this way when I was a teenager, as were so many of us. I was obsessed with images, and I would tape them to my wall so densely that they would cover the whole wall, and then I would tape another layer, another layer, another layer, such that when my parents moved out of the house when I was in college they had to peel it all down like a skin. And when I got to university I felt I had to become a “serious” photographer, which was coded as male, effectively. And based in a history from which I was learning that what I had been doing, and my affinities, were very feminised, and crafty, and something that teenagers do, or that mothers do with their children. And so as you were asking about self-making I was thinking about this, even if it wasn’t quite the thrust of your question; how many years and decades it took for me to come back around to this original intelligence, and consider it “serious”, and viable, and worthy of creative and intellectual enquiry. Worthy of the museum. And I still have to talk myself into that, and I show up at the MoMA with my dinky shoebox of pictures that are crinkled, that my kids have been licking, and I’m taping them up with blue tape. I have to self-make in perpetuity, I guess is what I’m saying.

AZ: I’m trying to both photograph and write, and I often find myself thinking of them in a polarised way, setting words and images up against one another. I don’t think that’s very useful, and I’m slowly trying to untangle those ideas. I wonder how you think about the difference, or not, between those aspects of your practice.

CW: Oh, it’s evolving. I have always struggled to conjoin the two, or make them see each other. There are countless examples of artists and artworks that do this really well — I know it’s possible, I see that work, and admire it deeply. Somebody like Fred Lonidier comes to mind, for instance, who I’ve been rather obsessed with since I was a teenager.

I’ve always reached to include text in the work because I have this writing practice, as you’re saying, and I’ve always felt like, if I could just jam them together they could become one thing, a singular force. And by and large I’ve been pretty unsuccessful at it. I try things and then I reel back, the fear being that I never want the text to read as a caption, or like an explanation in regard to the image, which of course in image-text hierarchy is how we understand them to function in relation: one explains the other. I’ve always had this belief that photographs can explain themselves, and in fact can be most powerful in doing that, in being their own agents. Not just explaining themselves, but not to flatten out their slippery meanings, or their contradictory meanings.

But that doesn’t stop me from trying; and I’ve tried. I write about art, I try writing as art, I try massaging my writing into art, so it’s this never-ending quest, but the place that I feel that I have been able to do it the most effectively is in artist’s books — not just because that’s where text “belongs” most conventionally, but I feel that I’ve been able to invert text and image more successfully there. My hope is that text becomes a thing that you can look at, and image becomes something you can read. Or that image explains text, as opposed to the other way around. Or they start to resemble each other in a way that I haven’t been able to do anywhere else. So I’m probably the wrong person to ask, because I have this perpetual frustration, but I don’t give up on it.

AZ: In Instructional Photography you mention Cortázar, Tolstoy, and Plath. It made me wonder how reading fiction or poetry had affected your work and your thinking.

CW: Quite a lot. I read a lot, although I read a lot more before I had children, so not as much as I once did; but I think about reading as informing my work more than anything else, and it’s something I talk a lot to students about, as we think about our constellation of influences. They name exclusively visual artists in their medium, and it just feels like there’s such a broad expansive world of creative enquiry and experimentation — what a shame to limit yourself. There’s not a right and wrong way to find influence, so that’s not to be too judgemental, but for myself — I’ve always been really interested in imagining possible worlds.

I think that is the imperative of feminism: to imagine what could be possible, and worlds that we have not yet built. And so in that regard fiction has been enormously important to me, not just feminist fiction, which I’m also really into, but this exercise in imagination, of which poetry also is excellent, and has the added benefit of playing with language structurally.

I’ve recently been on a big Marge Piercy kick. I’ve always been into Marge Piercy, but the novels, which are considered science fiction — women on the edge of time, and feminist parables. I’ve recently been into her poems, and damn, they are so good! I have to catch my breath as I’m reading them, and take breaks. They’re all sex and revolution, sometimes in the same poem. I find myself very moved by them. Some of the poems were written before I was born. I think that’s a good example of someone who does this really profound work of imagining and building parallel worlds.

The Last Safe Abortion will be published by SPBH/MACK on 24 May.

Every month I ask each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue.

Carmen Winant’s recommended reading:

The Moon is Always Female — Marge Piercy

The Old Drift — Namwali Surpell

Who’s Afraid of Gender? — Judith Butler

A huge thanks to Carmen Winant, and to you for reading. You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below:

This is one of those interviews I’ll be returning to like a well-thumbed book. What Carmen said about the “mistakes” — the blurs, the missed ISOs, the crinkled prints licked by her kids — hit me in the gut. Not because I’ve never heard that before, but because I needed to hear it again. Especially right now.

There’s something quietly radical about The last safe abortion—the way it insists on ordinariness as a site of resistance. Phone calls. Birthday cakes. A front desk. The kind of care that capitalism doesn’t count. The kind that can’t be viral. That’s what makes it sacred.

And the tension Carmen names — between wanting to make work about community and wanting to be in community — that’s the real frontier, isn’t it? Not just whether art is enough, but whether we’re willing to let it spill past its edges into the unphotographable.

Thank you both for this conversation. I didn’t realize how much I needed a reminder that quiet can still be a form of defiance.

Merci! Such a wonderful interview, with an artist I’ve admired for a long time. Thanks so very much.